Barbarians At The Gates? China’s Plan To Open Up Gated Communities Alarms Middle Class, Highlights Official Communication Problems

SHANGHAI — The latest challenge for China’s leadership is not the slowing economy, falling stock market or painful state enterprise reforms, but a bizarre controversy over whether to knock down the walls and open the gates of the nation’s private residential compounds.

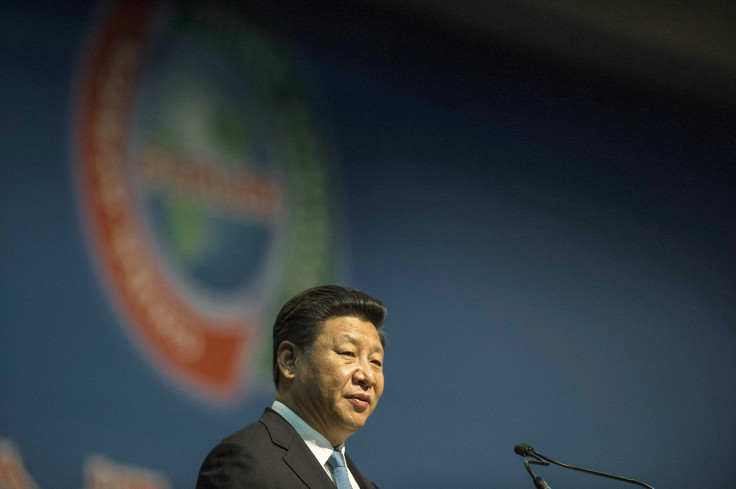

The row, which has stirred heated public and media debate and alarmed China’s middle classes, may be the latest evidence that while the Chinese leadership under Xi Jinping is keen to show it has the power to take tough and authoritative decisions — from reclaiming land in the South China Sea, to scrapping the one-child policy — it’s not always very good at explaining the rationale behind them.

After sowing international confusion and anxiety last summer with its sudden devaluation of its currency and massive intervention to halt falls on its stock markets, China was criticized widely by investors for failing to explain these policies clearly. More recently, the administration has tried to address some of the issues — Fang Xinghai, a cosmopolitan, U.S.-educated finance specialist was brought in as deputy head of China’s stock market regulator, and acknowledged to a global audience at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, China “should do a better job” of communicating with the outside world — but said the country was still in the process of “learning.”

A directive issued this week suggests the learning curve might be a steep one: Two months after holding a meeting on urban development — the first of its kind in nearly four decades, despite China’s breakneck urbanization in the interim — China’s leadership finally issued a directive spelling out the meeting’s decisions Sunday. Among pledges to create greener cities with more public transport, the ruling contained the apparently throwaway line that “no more enclosed residential compounds will be built in principle [and] existing residential and corporate compounds will gradually open up so the interior roads can be put into public use.” This would, it said, “save land and help reallocate transport networks.”

Anyone who has spent time in a Chinese city will know that if there’s one thing that distinguishes China’s urban middle classes — apart from loving cars and generally having only one child — it’s that a significant and ever-growing proportion of them live in modern residential compounds. Based on a model imported by developers from Hong Kong and other parts of Asia, such communities often number thousands of residents, living in high-rise blocks situated around a central garden and, sometimes, a children’s play area. These compounds are often open to pedestrian access, but many forbid entry by the cars of nonresidents while the more luxurious gated communities, which may feature swimming pools and gyms as well as underground parking, may also prevent passers-by from entering.

And since property in many Chinese cities is as expensive as in cities in the west while average incomes are significantly lower, many Chinese families have put much of their life savings into buying such properties, which are seen as providing a certain degree of peace and safety in the midst of China’s hectic and often chaotic urban environment. On top of this, residents also are required to pay management fees for the shared facilities.

So it’s hardly surprising the sudden announcement aroused controversy as the news began to filter through to residents Monday. Within a few hours, a survey on Sina.com, China’s biggest news portal, had garnered 85,000 responses, with more than three-quarters of respondents opposing any opening-up of gated communities. Residents expressed worries about noise, safety, and property values, with 87 percent saying they would demand compensation if the communities were opened up, the South China Morning Post reported.

Later that day, China’s Guangming Daily newspaper published an article supporting this demand and suggesting the government would have to take on management of compounds, now under private security firms, if it enforced the directive. Lawyers meanwhile suggested the policy might contravene China’s 2007 property law saying homeowners were the joint owners of the public space in these compounds while business analysts warned it might not only hit property prices and “damage the interests of some apartment owners,” but could “hurt the already weak second hand housing market in some Chinese cities.”

As this storm raged online, with many viewing the directive as implying “knocking down the walls” of residential compounds, there was little direct response from the people in charge, as so often is the case in China. State media began quoting experts, though it wasn’t clear if they were sure of the facts. “It doesn’t mean simply knocking down walls,” some said. The rule mainly applied to the biggest compounds, particularly in the north of China, and wouldn't affect those in Shanghai, which aren’t as big, added Wu Zhiqiang, deputy dean of Shanghai’s Tongji University, and a top urban planner, apparently referring to private neighborhoods in some Chinese cities that house tens of thousands of people. He also suggested compounds owned by state enterprises and institutions were a major target, not just private residential areas.

Officials from government departments, put on the spot by Chinese media, did their best to respond. Asked whether the guidelines clashed with China’s property law, an official from the supreme court told reporters more details would emerge when a detailed bill went through China’s Legislature but, apparently keen not to be seen criticizing a central directive, he suggested gated communities were “a product of the agrarian era. Now we’re in the new era of 21st century industrialized, informationized and new-style urbanization. We need new concepts and experiments,” Shanghai news website The Paper reported.

The Shanghai Morning Post, meanwhile, republished an op-ed comment from the website of the official People’s Daily on its front page, reassuring citizens: “Officials didn’t just think this decision up off the top of their heads.” The author suggested that “instead of complaining about new things, people should reflect a bit more,” adding closed communities are a major cause of traffic jams. However, even this author acknowledged officials should take into account public worries about noise and safety, acknowledging, “There might need to be some legal clarification about ownership.”

Finally, official media Wednesday carried a statement from China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development, saying the directive only contained “general guidelines.” It said local governments would be required to draw up plans to implement these, and would be “cautious” in “dealing with all kinds of interests involved, and the public would “definitely be consulted.” At the same time it criticized “misunderstandings” about the new regulations — though, as the South China Morning Post noted, “without elaborating on what the public was getting wrong.”

It did little to quell the debate. “China may have the largest number of walls in the world. Walls reflect China's unique cultural tradition and people’s psychological line of defense,” a commentary in the official Global Times said Thursday. Maybe the government could wait until 70-year land-use rights for existing compounds expired, before opening them up to the public, one commentator suggested. Another said the government should take “professional suggestions from urban design researchers.”

And many residents seem to find it hard to imagine the rules being implemented.

“Open up our roads to cars? Hahaha,” cackled the guard at a gated community near central Shanghai’s Nanjing Road West, in response to a question from International Business Times. “That would be really strange! If we won’t let you in, you can’t come in!”

Lost in all of this uproar is the fact that some experts agree such a change in China’s urban planning model might not be a bad idea.

James Brearley, director of Shanghai architecture practice B.A.U., which has carried out planning for many new Chinese urban districts, has long complained China’s residential compounds are too large. It might be good for real estate developers, he says, but it often leads to long blank walls on streets, “sometimes with a fence of more than 500 meters or even 1 kilometer in one direction,” and stifles street life.

“Cities need to be designed in self-contained subdistricts which act like small towns, offering the chance to work, live, shop, play, learn,” Brearley, author of a book, “Networks Cities,” aimed at Chinese planners, told IBT. “Small blocks are beneficial because they make the city walkable, with more surface area for buildings to engage with the street. Unfortunately, Chinese urban planning departments are still segregating land uses. And with fewer streets each street needs to be wide and gets busy with traffic.”

However, Brearley said judging by official comments so far, it appears the new rules did not spell the end of China’s “traffic and car obsessed model.”

“It seems the new rules are not about improving the walkability and livability of cities, [but] only about reducing traffic congestion,” he said.

And others have suggested there could be another motive for the leadership’s proposal: “I think they have announced this because gated communities are so clearly elitist,” said Michael Cole, founder of Shanghai real estate intelligence website Mingtiandi. “The impact on traffic is likely to be a secondary consideration.”

Targeting private residential compounds would certainly appear to fit in with the populist stance of President Xi Jinping, who has sought to make his tough attitude on social liberties acceptable to the public by promising a fairer society. He’s launched not only an anti-corruption campaign, but also a crackdown on extravagance by officials, amid a greater emphasis on traditional socialist values. Private residential compounds — which often have blatantly exclusive names, such as Rich Gate or Top of City — seem to go against this, rubbing in the fact China has become one of the most divided societies in the world, according to the Gini Coefficient measure. Their construction has also led to the demolition of many old downtown neighborhoods, leading to the relocation of ordinary residents to remote suburbs, and contributing to the unaffordability of city center property for many citizens.

But the controversy the announcement has stirred up among China’s middle classes suggest China’s leadership is taking a big risk in using its increasingly centralized power to ram policies through without consultation in a society where people have become used to more debate since the arrival of the internet age some 15 years ago.

A state newspaper Wednesday called for a greater role for public opinion in the drafting of laws, something the government is disinclined to approve — Xi recently said public opinion and that of the party should be the same.

The issue of gated compounds is one area where the government is out of step with the middle classes, which can’t imagine Chinese life without them.

“I don’t think there’s much chance they’ll implement this in Shanghai,” said a relaxed-looking resident of a luxury compound that takes up an entire city block in central Shanghai as he took his young son and dog for a walk through the leafy garden. “I think these rules are aimed at very big compounds. And even if they tried to implement them in Shanghai, it would probably would take 10 years — everything is slow to happen in China!”

Alienating this growing demographic — and potentially damaging China’s property market, in which so many people’s wealth is tied up — is a risky strategy for China’s leadership at a time when the country faces a range of economic challenges. And Mingtiandi’s Cole suggested it would be hard to make the policy stick across China.

“Given the level of influence that gated community dwellers have, this new rule is likely to be unenforceable in China, except in some isolated cases,” he said.

While the authorities may have identified genuine problems with China’s urban development — and some would say their desire to create more human scale living environments is overdue — the incident has once again highlighted the government’s inadequacies in communicating with Chinese citizens as well as the outside world.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.