Beyond Boko Haram: The Tangled Roots Of Northern Nigeria's Complicated Conflict

Nigeria may be one of Africa's richest countries, but for years its northern regions have been plagued by deadly violence and wanton destruction. At the center of it all are militants belonging to an Islamist group called Boko Haram, whose campaign of violence and terror has killed thousands of people since 2009. What started as a movement to enforce a strict interpretation of Shariah, or Islamic law, in northeastern Nigeria has morphed into an indiscriminate campaign of violence targeting men, women, children, Muslims, Christians, troops, political figures and innocent civilians.

The name "Boko Haram" has become a byword for instability in northern Nigeria, but its militants are not the only ones to blame; the roots of this turmoil are all-encompassing. They include chronic underdevelopment, misallocation of government resources and a wide-ranging patchwork of criminal groups whose connections to Boko Haram are hazy. The response from the state has hardly helped matters.

"The government response is very robust, and the problem is that it's often extremely violent and indiscriminate -- not investigative at all," James Verini, a correspondent for National Geographic who investigated the situation in northern Nigeria, said in an interview. "JTF [the military's Joint Task Force] has taken on this campaign of mass suppression and retributive violence, and regular citizens are getting caught in the crossfire. The government is basically trying to carry out a counterinsurgency in the worst possible way."

During his travels with photographer Ed Kashi, Verini discovered that the name "Boko Haram" had taken on a life of its own. He wrote in the November issue of National Geographic magazine:

In the Sahel, home to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and to the jihadists who until recently controlled northern Mali, Boko Haram has emerged as the nastiest of a nasty new breed. Calling for, among other things, an Islamic government, a war on Christians, and the death of Muslims it sees as traitors, the group has been connected with upwards of 4,700 deaths in Nigeria since 2009. And although Nigeria, with 170 million inhabitants, is the continent’s most populous country (one in six Africans is Nigerian) and has sub-Saharan Africa’s second largest economy, even by its immense standards the carnage attributed to Boko Haram is immense.So much so that unofficially, in the national collective consciousness, Boko Haram has become something more than a terrorist group, more even than a movement. Its name has taken on an incantatory power. Fearing they will be heard and then killed by Boko Haram, Nigerians refuse to say the group’s name aloud, referring instead to “the crisis” or “the insecurity.” “People don’t trust their neighbors anymore,” a civil society activist in Kano told me. “Anybody can be Boko Haram.” The president, Goodluck Jonathan, an evangelical Christian, wonders openly if the insurgency is a sign of the end times.

Nigeria's economy has grown by an average of 6.8 percent annually since 2005 and could soon eclipse that of South Africa as the biggest on the continent. The country is rich in oil, with about 37 billion barrels of proven crude reserves, but this has become something of a liability -- the capital-intensive energy sector does little for employment and broad-based growth, leaving an unemployment rate of at least 23 percent.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the north, a majority-Muslim area that has benefited far less than the south when it comes to development and infrastructure. The allocation of government revenues per capita in the north is about half the rate for the south, and about three-fourths of the northern population live in absolute poverty, as compared to about two-thirds for the country as a whole.

Some northern Nigerians are working to address these issues, including Shehu Sani, an activist who runs a human rights and political advocacy group called the Civil Rights Congress in the central northern city of Kaduna. Sani, who was a political prisoner before Nigeria's civilian government took over in 1999 and is now running for a senatorial seat in the 2015 election, disparages the JTF's reaction to militant violence. He tried to arrange talks between the government and Boko Haram leaders in 2011, but says the government's unwillingness to meet any demands halfway has consistently scuttled discussions.

"The administration is hiding behind the state of emergency to commit evil under the guise of fighting terror," Sani said by phone. "There should be some commitment on the side of the government to find a solution, but it is not possible to organize any form of dialogue while they are enforcing this state of emergency."

President Jonathan declared a state of emergency in the northeastern states of to Borno, Yobe and Adamawa in May, sending thousands of extra troops to quash militant movements there. But the violence continues; a clash between troops and militants on Oct. 24 killed at least 127 people in Yobe's capital city of Damaturu, and an attack on a wedding convoy in the Borno city of Banki killed at least 30 on Saturday.

It remains unclear whether Boko Haram alone is to blame for these tragedies, since the organization has become increasingly opaque in recent years. "The group has metastasized -- they've gotten more broad, but they've also gone underground," Verini said. "West Africa and the Sahel have become a sort of welter of various jihadist groups; the movements are becoming difficult to distinguish."

Nigerian troops have been strongly criticized for their actions in northern Nigeria. Human Rights Watch reports that Nigerian soldiers and police have committed serious human rights abuses against citizens who had little or no links with the militia, including summary executions, destruction of property and arbitrary arrests. The organization estimates that of the 4,700 people who have lost their lives in connection with the insurgency, nearly half have died due to abuses committed by national security forces. Amnesty International has documented inhumane treatment of suspects in Nigerian prisons that led to the deaths of more than 950 detainees in 2013 alone.

"What human rights groups are saying is a fact -- a truth on the ground," Sani said. "At my office here in northern Nigeria, I receive many calls reporting gross violations committed by the Nigerian military. People have been detained and people have been killed indiscriminately."

Distrust of the central government, weak local political institutions and widespread underdevelopment have made northern Nigeria fertile ground for radicals and militants, who draw on popular discontent to raise support for their own aims. Such was the case for Boko Haram, which began as a group of worshippers at a mosque in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state. They moved to the eastern town of Kanama in 2002 to practice a more hardline version of Islam, but conflicts with the police eventually spurred the adherents to move back to Maiduguri, where a cleric named Mohammed Yusuf became the group's spiritual leader. The movement spread to several states as years passed, evolving into a governance system based on Shariah.

Following clashes with local authorities, Yusuf was killed in 2009 -- an event that radicalized the group still further. Hundreds of attacks have been attributed to Boko Haram since then, and the militia made international headlines in 2011 when its members bombed the United Nations facility in the capital city of Abuja, killing 23 people.

Boko Haram can be roughly translated from the Hausa language to mean "Western education is forbidden." But this is not the organization's official moniker; it was first used by outsiders as a derisive nickname for the conservative sect. The group refers to itself in Arabic, as Jama-atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda-awati Wal-Jihad, which means "The Sunni Organization for the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad." This incongruity over the group's designation is more than skin-deep; it reflects some confusion over the group's original aims. Boko Haram began as a locally focused movement first and foremost, not an anti-Western one. Though it has expanded since its inception to include various cells -- some of which may have connections to global movements like al-Qaeda -- many observers believe the Nigerian government has painted the group as more of a universal threat than it actually is, and that police have neglected their investigative duties and pinned various crimes on the group even when unaffiliated criminals were likely involved.

Critics of the government allege that for the administration of President Goodluck Jonathan, Boko Haram has become a political tool -- a way to encourage foreign defense partnerships and an excuse to clamp down on dissent in northern regions where support for the Abuja administration is low.

"Yes, the government has become involved. The fight against Boko Haram has become big business for local companies and international consultants," said Sani. "The problem can only be solved if the government accepts the fact that the use of force alone cannot address the issue."

But the government shows no signs of changing its tactics; its responses to allegations of wrongdoing are consistently vague and unapologetic. For residents of northern Nigeria, years of confusion and terror don't appear to be coming to an end anytime soon. That leaves civilians to interpret the turmoil as best they can while the death toll continues to rise.

"Some people take the government line that Boko Haram is a dangerous jihadist group, some say it's a group with legitimate grievances against the government, some people think it's a political tool, and other people say Boko Haram is just a figment of the public's imagination," Verini said. "The common denominator is that no one knows much. They just know that there's a great deal of violence, and they're scared."

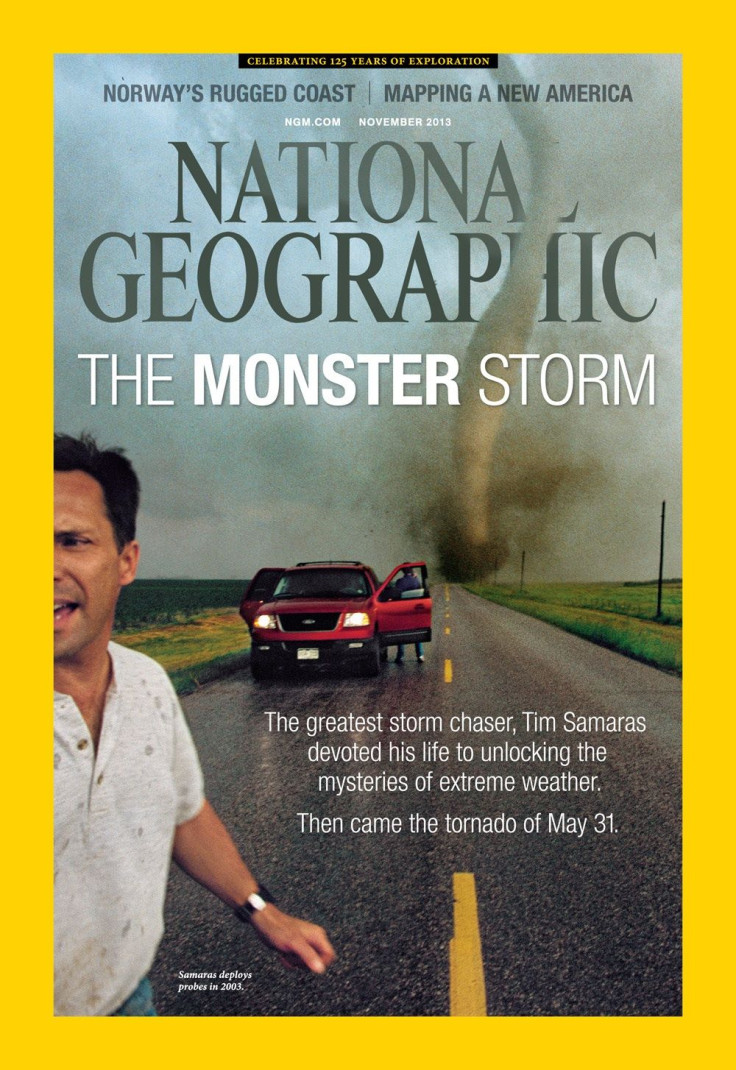

Images are from the November issue of National Geographic magazine.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.

Join the Discussion