Boko Haram: United States Intervention In Nigeria Is Complicated, Officials Say

Boko Haram members have killed thousands of people, kidnapped hundreds of children and claimed responsibility for increasingly violent attacks around northern Nigeria for more than five years. Hundreds died during the Islamist militant group’s latest and deadliest massacre in the city of Baga.

A week later, one reporter asked the White House an obvious question at a briefing, “Why haven’t we seen U.S. intervention in Nigeria?”

The U.S. has employed military intervention to stop brutal campaigns before, and recently announced plans to send 1,000 soldiers and personnel to help Syrian rebels fight the Islamic State group, another terrorist organization known for widespread brutality, as the New York Times reported. But Nigeria presents a difficult case.

Although Boko Haram is an obvious problem, a U.S. decision to work with a government associated with corruption and possible war crimes presents a dilemma. But experts say there are ways to intervene without a military presence. It will just take time.

In response to the reporter’s above-referenced question, White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest answered that the U.S. “remains deeply concerned” by reports of violence in northern Nigeria and is helping with “counterterrorism assistance” in various ways. They include information-sharing and supporting programs that provide “positive alternatives to communities most at risk of radicalization and recruitment.”

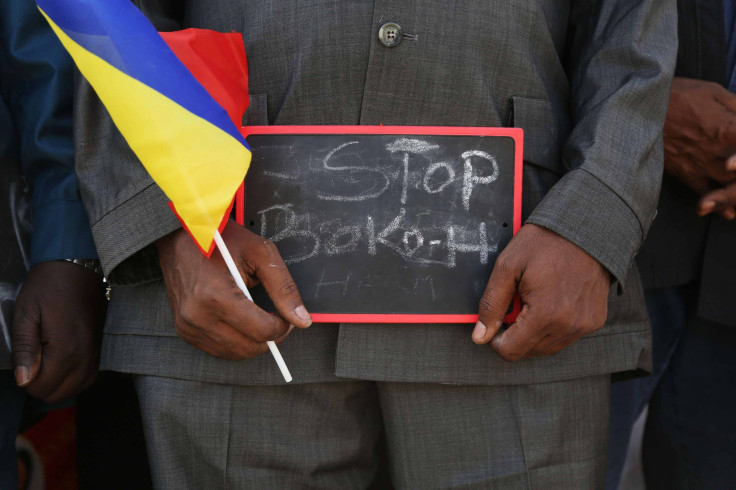

After Boko Haram militants kidnapped more than 200 schoolgirls from the town of Chibok last year, activists drew international attention to the incident with the social-media hashtag #BringBackOurGirls. As CNN reported at the time, the U.S. used drones to help search for the girls, but did not provide any direct military intervention.

“There is a tremendous capacity that our military has to protect our interests around the globe,” Earnest said at the briefing Thursday, “and that ultimately is the question ... how do you sort of balance America’s national-security interests with the variety of capabilities that the U.S. military has?”

When the U.S. State Department designated Boko Haram as a Foreign Terrorist Organization in November 2013, citing its responsibility for the deaths of thousands and possible links to al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, it also was careful to note something else.

“These designations are an important and appropriate step, but only one tool in what must be a comprehensive approach by the Nigerian government to counter these groups through a combination of law enforcement, political and development efforts, as well as military engagement,” the State Department said.

But U.S.-Nigeria relations are complicated, likely because of current President Goodluck Jonathan, who has been accused of allowing widespread corruption, violence and even war crimes, said Max Abrahms, a professor of political science and terrorism analyst at Northeastern University.

“The nature of that bilateral cooperation never truly materialized because the Goodluck Jonathan administration also has blood on its hands,” Abrahms told International Business Times.

Although Boko Haram’s abuses are horrific, Nigerian security forces aren’t blameless themselves.

Amnesty International recently documented large-scale human-rights abuses by the Nigerian military and police forces in a report titled “Welcome to Hell Fire.” These abuses included torture, enforced disappearances and the deaths of people in custody. But even more troubling for Amnesty researchers was the impunity with which Nigerian forces operate.

“Security officials are rarely held accountable are rarely held accountable for failures to follow due process or for perpetrating human-rights violations such as torture,” Amnesty International said in the report. “The absence of acknowledgement and public condemnation of such violations by senior government officials further assists in creating a climate for impunity and raises serious concern about the political will to end such human rights violations."

Earnest pointed to this problem at his press briefing. “We’re going to keep the pressure on the security forces to do a better job of protecting their population from the violent extremists, while at the same time those security forces do a better job of respecting basic human rights,” he said.

But John Campbell, the former American ambassador to Nigeria, argues the U.S. should do more.

“The United States cannot be indifferent,” Campbell wrote in a November report for the Council on Foreign Relations. “Boko Haram poses no security threat to the U.S. homeland, but its attack on Nigeria, and the Abuja response characterized by extensive human-rights violations, does challenge U.S. interests in Africa.”

Nigeria recently earned the title of biggest economy in Africa with a gross domestic product of close to $510 billion, and it is hailed by many as an example of democracy in the region after its citizens broke from a generation of military rule. According to Campbell, instability in Nigeria could spread to the rest of West Africa and possibly provide a base for other militant groups hostile to the U.S.

Campbell acknowledged the abuses of the Nigerian military and the possibility that an American presence could increase anti-Western sentiment in the region, but urged U.S. lawmakers to take action in a different way, especially during the coming elections, which experts say are likely to be even more tense than usual because of Boko Haram’s presence.

“Washington needs to recognize unpalatable realities as it devises its Nigeria policy for both the short term in the run-up to elections and for the long term afterward,” Campbell wrote. He noted that through connections with local human-rights leaders and other methods the U.S. can help lay the groundwork for the future.

“The United States can assist those in Nigeria working for a democratic trajectory only at the margins,” he wrote. “But it is worth the effort.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.