Climate Change Is Putting Fragile North Atlantic Coral Populations At Risk

We already know that climate change-induced rise in ocean temperature and acidity has killed at least a quarter of the corals in the northern and central parts of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. It turns out these aren’t the only corals bearing the brunt of global warming.

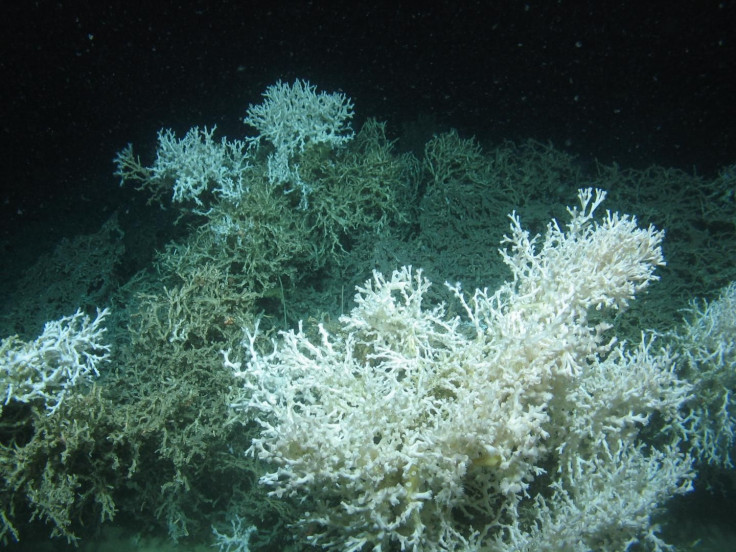

In a new study published in the latest edition of the journal Royal Society Open Science, a team of researchers revealed that deep-sea corals in the North Atlantic Ocean are now under threat from climate change-caused rise in average winter temperatures in Western Europe.

The researchers focused on the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa — a species whose population is maintained by tiny, fragile coral larvae that drift and swim hundreds of miles on ocean currents. Using computer simulations that incorporated the effects of changing ocean currents, they found that changes in weather conditions — especially during winters — could drive larvae away from the weakly connected protected marine areas established to safeguard coral populations.

“We can't track larvae in the ocean, but what we know about their behavior allows us to simulate their epic journeys, predicting which populations are connected and which are isolated,” lead researcher Alan Fox from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Geosciences said in a statement. “In less well connected coral networks, populations become isolated and cannot support each other, making survival and recovery from damage more difficult.”

The findings are similar to a recent study that simulated the movement of coral larvae over a 3,100-mile stretch separating populations in eastern and western Pacific. Using their simulations, the researchers found that even during the extreme El Niño event of 1997-1998, when shifting ocean currents promoted long-distance dispersal, the larvae could not survive long enough to cover the vast expanse separating coral colonies in the east and west Pacific.

Responding to the findings of the new study, the World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF) in Scotland said that it highlighted the need for “a coherent network of well-managed, properly resourced marine protected areas.”

“Globally, healthy oceans are important for wildlife and the many coastal communities that depend on them for a living. However, rising temperatures and other negative impacts caused by climate change put all this at risk,” a WWF spokesman reportedly said. “Hopefully, this research will help us better understand how to address these and other challenges facing our marine environment.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.