Davos 2013: IIF Warns Of 'Boom-Bust Cycle' In Emerging Markets

Is there a bubble ready to pop? Well, a global banking group is sounding the alarm.

The Institute of International Finance said in its latest half-yearly review of capital flows into emerging markets -- prepared ahead of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland -- that private sector flows have “revived strongly” thanks to investors’ taking a more risk-friendly attitude since mid-2012.

Investors have been pouring money into the emerging market – pushing debt issuance to record highs in 2012 -- as they seek higher returns than can be found in developed bond markets subdued by central bank bond-buying.

But the “easy money” conditions have perhaps created a false sense of confidence.

While the leading rich economies have kept interest rates at historic lows and are taking action to ease policy even further, with Japan announcing unlimited asset buying on Tuesday, there will be an end to this money-printing frenzy.

And sudden turns in monetary policy could lead to a “boom-bust cycle” in emerging markets if investors are unprepared, the IIF warned.

The potential of a tighter monetary stance by the U.S. Federal Reserve – given the recent decline in U.S. unemployment – implies a degree of heightened risk in the longer term.

To shore up the economy, the Fed has cut its key interest rate to rock-bottom levels and has embarked on several rounds of quantitative easing – essentially, pumping money into the financial system. Other major central banks around the world have also been pursuing low-interest rate policies to try to stimulate growth and reduce high unemployment.

But minutes from the Fed’s December policy meeting showed officials were split on whether to keep buying assets until the end of 2013, raising the possibility of an early end to QE3.

“Investors may be unprepared for a reversal of interest rates,” Charles Dallara, managing director of the IIF, said in a statement. “This needs to be seriously considered to avoid disruption.”

Perhaps the most pertinent precedent is the experience of 1993-94, when the Fed changed course away from its previous “low-for-long” policy and raised interest rates, the institute said.

The Fed had cut the funds rate to 3 percent in September 1992, and had signaled a willingness to maintain low rates to ensure a recovery through 1993 (Europe was in recession in 1993).

By early 1994, the U.S. was almost three years into an expansion, and the Fed decided that it was time to hike rates. The results for financial markets were stunning.

Far from anticipating a shift in direction from the Fed, market participants had locked into many “low-for-long” trades. As these trades began to lose money in a rising rate environment, there was a scramble to exit, which dragged down all major bond markets.

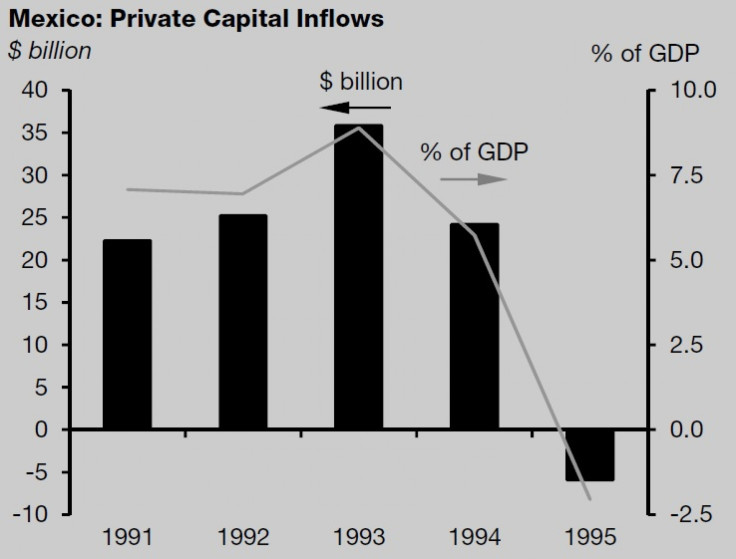

According to the IIF, higher Fed funds rates initially led to a steeper, not a flatter, U.S. yield curve. European bond markets sold off in lock step with U.S. bond markets, even though European central banks (notably the Bundesbank) were still in easing mode. Meanwhile, emerging market asset prices (which had risen sharply in 1991-93) slumped (in two stages) through 1994 and early 1995.

Most importantly, the IIF pointed out, private capital flows to Turkey and to Latin America – especially Mexico – collapsed, culminating in near-default by Mexico in the first quarter of 1995.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.