Electric Cars Would Lower UK Oil Imports By 40%, But Only With Much Wider Adoption: Report

Outside of Norway and the Netherlands, electric vehicle market share remains under 1 percent, even in environmentally progressive countries such as Iceland and Sweden. While the benefits of wider electric-car adoption -- including reduced urban air pollution and a lower long-run cost of vehicle ownership -- are well known, researchers in Britain have put some numbers behind the economic effects of battery-powered transport.

Assuming a much broader acceptance of electric cars than exists today in Britain, researchers concluded that the country’s dependence on oil imports could drop by 40 percent, saving drivers 600 British pounds ($905) a year in fuel costs, which would eventually offset the higher upfront price of electric cars. At the same time, the overall economic impact of a broad shift toward electric cars would yield a modest national economic benefit. The implications in the report go beyond Britain, suggesting that countries that depend on oil imports and use more renewable energy have the most to gain economically from investing in electric-car infrastructure.

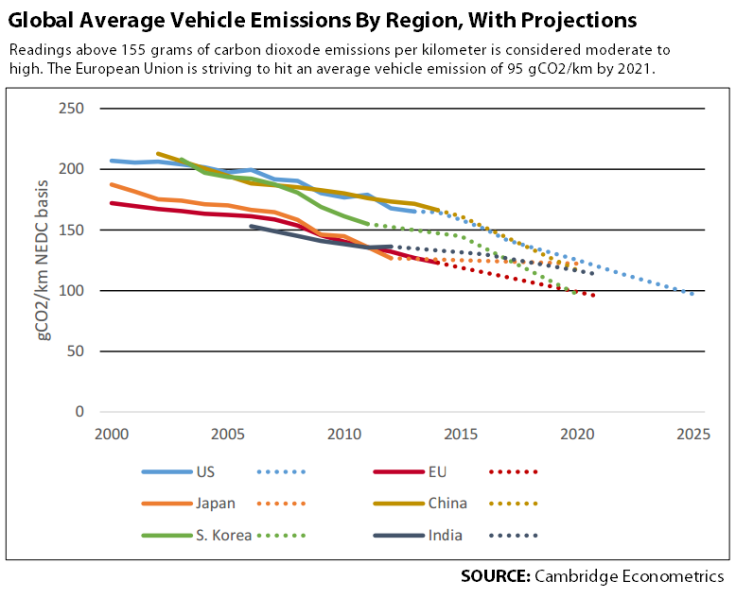

“Based on the current body of evidence, we conclude that a transition to low carbon cars and vans would yield benefits for U.K. consumers and for the environment (both in terms of reduced greenhouse gas emissions and reductions in local air pollution), and have a neutral to positive impact on the wider economy,” said Cambridge Econometrics, an independent consultancy, in the study that was released Monday. But in order to get there, governments and the private sector will have to greatly increase infrastructure investment -- and soon.

In order to greatly reduce the harmful pollutants emitted by internal-combustion engines by mid-century, the report estimates Britain would have to grow electric-car use from less than 20,000 vehicles today (out of about 35 million vehicles last year) to more than six million by 2030 and 23 million by 2050. This wouldn’t be an easy task.

To get tens of millions of electric cars on Britain's roads over the next 15 years, the government and private sector would have to build out the charging-station infrastructure to allay consumer concern about running out of power before finding a place to plug in, a phenomenon known as “range anxiety.” According to a report last week from the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, an organization based in California, range anxiety lessens over time among electric-car owners. However, it’s commonly understood in the industry that electric-car skeptics aren’t going to get over their concerns until they see a combination of longer electric-car ranges (most electric cars travel less than 100 miles per charge), faster charging times (it can take 20 minutes to “fill up” an electric car to 80 percent at a fast-charging outlet) and more charging stations.

“There will be a transition in the next five to 10 years but you won’t see a sudden shift to electric vehicles until consumers have got over their ‘range anxiety’ concerns -- and that will only happen with infrastructure spending,” Philip Summerton, one of the report’s authors, told the Guardian in a report published Tuesday.

In January 2013, the European Commission proposed a $10.7 billion program to build out electric-car charging stations across the European Union. In Britain the plan would have boosted the number of these outlets from 703 in 2012 to 1.22 million by 2020. Other European Union states would have seen similar increases, but by the end of 2013, EU member states, including Britain, successfully delayed the measure, citing the high costs.

The report was commissioned by the European Climate Foundation, a nonprofit environmental public policy group. Read the summary here. Read the full copy here.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.