Embattled Ex-Chesapeake CEO Aubrey McClendon, Who Helped Fuel The US Shale Revolution, Dies In Car Wreck

Aubrey McClendon, the former CEO of Chesapeake Energy Corp. and one of the most successful energy entrepreneurs of recent decades, died in a car wreck Wednesday at age 56, Oklahoma City police confirmed. McClendon died after driving his vehicle into a wall, CNBC reported.

McClendon's death comes one day after the U.S. Department of Justice indicted him on a charge of conspiring to rig bids for crude oil and natural gas leases while at Chesapeake from late 2007 to early 2010. McClendon had denied the charges and vowed to fight them.

Police were investigating the cause of the crash Wednesday, Reuters said, adding that the vehicle was so badly burned that the police were unable to tell if McClendon was wearing his seat belt.

A native of Oklahoma, McClendon attended Duke University before launching his company, Chesapeake Operating, in 1989. At the time, the U.S. was well past its boom in oil and gas production, but engineers in Texas, especially George P. Mitchell, were making exciting discoveries in the oil patch, hinting that vast stores of crude oil and natural gas could soon be unleashed from shale rock formations deep underground.

McClendon pounced. Chesapeake in the early 2000s began feverishly snapping up natural gas leases and wells across Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana before heading east to Pennsylvania and Ohio. The rest of the energy industry soon followed suit, sparking a U.S. shale drilling boom and transforming the U.S. from a bit player to a major force in the global energy sector.

“I’ve known Aubrey McClendon for nearly 25 years. He was a major player in leading the stunning energy renaissance in America. He was charismatic and a true American entrepreneur. No individual is without flaws, but his impact on American energy will be long-lasting,” billionaire oil tycoon T. Boone Pickens said in a statement Wednesday.

“He’s always been a ferociously aggressive landman. His appetite created the need for other people to effectively keep up,” Gary Sernovitz, an oil analyst and book author, said of McClendon, who served as CEO of Chesapeake Energy Corp. until 2013.

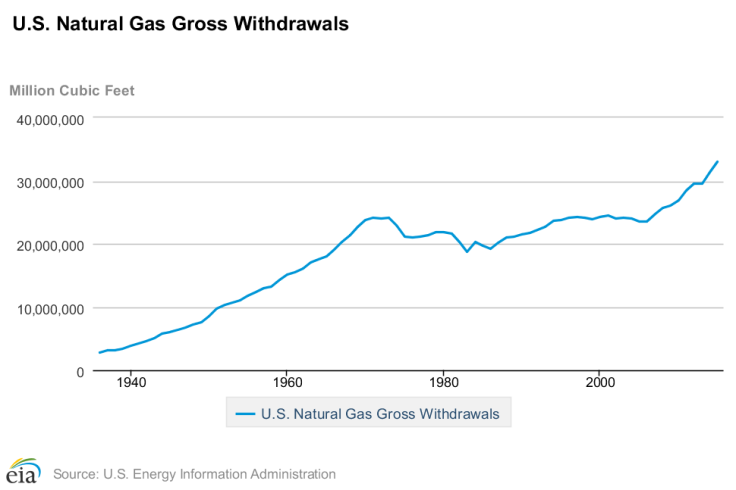

That voracity of appetite for shale development helped propel the U.S. from an energy importer to an exporter as volumes of oil and gas surged in the last decade. The supply boost eventually fueled a glut that has dramatically slashed prices and, in a twist of irony, left companies like Chesapeake on the verge of bankruptcy.

McClendon’s land rush also left him mired in legal troubles. The U.S. Justice Department Tuesday charged the businessman with conspiring to suppress prices paid for oil and natural gas leases in northwest Oklahoma.

The indictment accused McClendon of orchestrating a conspiracy in which two large oil and gas companies -- left unnamed -- agreed not to bid against each other for the purchase of several leases from December 2007 to March 2012. The companies would decide ahead of time who would win the lease.

McClendon’s actions “put company profits ahead of the interests of leaseholders entitled to competitive bids for oil and gas rights on their land,” Bill Baer, assistant attorney general for the department’s antitrust division, said in a statement Tuesday. “Executives who abuse their positions as leaders of major corporations to organize criminal activity must be held accountable for their actions.”

McClendon denied all charges, calling the indictment “wrong and unprecedented,” according to a media statement.

Gordon Pennoyer, a spokesman for Chesapeake, told reporters the company “has been actively cooperating for some time” with the federal probe. “Chesapeake does not expect to face criminal prosecution or fines relating to this matter,” he added.

The Justice Department said McClendon’s indictment was the first case in a nearly four-year federal antitrust investigation into price fixing, bid-rigging and other anti-competitive actions in the oil and gas sector. The probe began after a 2012 Reuters investigation of Chesapeake’s actions in Michigan. The news outlet found the energy company discussed with a rival how to suppress land lease prices in the state. Chesapeake settled with the Michigan attorney general in 2015 by agreeing to pay $25 million into a compensation fund for landowners.

However Chesapeake obtained the leases, the speed and volume at which the company grabbed land has helped to reshape America’s energy landscape.

McClendon was among the first energy executives to capitalize on recent advances in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. While the technology had existed in some form for over a hundred years, it wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that engineers and scientists discovered cost-effective, higher-volume methods for extracting shale oil and gas from tight rocks buried thousands of feet below the surface.

Mitchell, the Houston oilman, helped pioneer the modern fracking process in Wise County, north of Fort Worth, an area now known as the Barnett Shale. He later sold his firm, Mitchell Energy Resources, to Oklahoma City-based Devon Energy in 2001. Devon engineers soon combined fracking with a little-used technique called horizontal drilling, which enabled oil and gas companies to vastly boost the output of wells from shallow layers of rock.

But shale development progressed relatively slowly, until McClendon and Chesapeake turned up the heat, said David Burnett, director of technology at the Global Petroleum Research Institute at Texas A&M University in College Station.

“The industry is very conservative. No one likes to be first,” he said. Chesapeake was a “first follower,” he added. “They put their chips on the right number during the early shale boom.”

From the Barnett Shale, Chesapeake expanded into Haynesville, Fayetteville and Eagle Ford shale formations in Texas and the middle U.S., along with the natural gas-rich Marcellus and Utica shales in the eastern U.S. McClendon, meanwhile, became a billionaire as Chesapeake aggressively outbid competitors for land leases and tapped highly productive wells in shale fields across the country.

“That appetite was one of the accelerating factors in the shale revolution in that period,” said Sernovitz, who wrote about Chesapeake’s rise in his new book “The Green and the Black: The Complete Story of the Shale Revolution, the Fight over Fracking and the Future of Energy” (St. Martin’s Press).

Since 2000, the number of U.S. natural gas wells and gas condensate wells has surged over 50 percent, from nearly 342,000 wells at the turn of the century to nearly 515,000 wells in 2014, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Fracking has similarly fueled a boom in U.S. shale oil, which now accounts for about half of total U.S. crude oil production, the EIA estimated.

Rising U.S. oil output is padding the global supply at a time when the world’s thirst for crude is stagnating. The International Energy Agency recently estimated that total oil supplies could exceed demand by 1.5 million barrels a day in the first half of 2016. The market imbalance sent prices plunging from above $100 a barrel in June 2014 to about $35 a barrel this week for U.S. benchmark crude.

U.S. natural gas prices have similarly plummeted in recent years as drillers, including Chesapeake, unleashed vast quantities of the fuel. Prices this week touched a 17-year low after federal data showed a swell in inventories, spurred by the fracking boom and higher-than-normal winter temperatures. Natural gas futures for April delivery settled to $17.11 a million British thermal units Monday on the New York Mercantile Stock Exchange – the lowest closing price reached since March 1999.

Yet even as prices slumped in recent years, Chesapeake kept growing and drilling. The company now has roughly $11.6 billion in outstanding debt.

Shares in Chesapeake (NYSE:CHK) have plunged over 90 percent in the last five years to just above $3 a share.

McClendon stepped down as CEO in 2013 amid a liquidity crunch and concerns over corporate governance. The former executive reportedly sold hundreds of millions of dollars in Chesapeake stock to raise cash for himself, using the loans to pay for his share of the cost of drilling wells, a 2012 Reuters investigation found. He went on to found American Energy Partners, a company that invests in shale fields globally.

Forbes estimated McClendon’s net worth at $1.2 billion in 2011. More recently, following the industry downturn, the total value of his personal holdings was estimated at $500 million, according to the website Celebrity Net Worth.

When he wasn’t wildcatting, he acquired lavish assets, including a French winery and a $12 million antique map collection. McClendon, who was also a part-owner of the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder basketball team, gained renown in the sector for his approach to running Chesapeake: Employee perks included on-site Botox treatments at the Oklahoma City headquarters, Reuters previously reported.

Sernovitz said Chesapeake was a “victim of its own success,” although he said the company’s fate doesn’t quite offer a neat morality tale of excess and blind confidence. Sernovitz said the fracking renaissance unleashed unexpected volumes of gas, particularly in the Marcellus shale, where drillers initially only expected to find incremental sources.

“Chesapeake had an early mover disadvantage,” he added. “I don’t think anyone could look back and say they could’ve predicted the prices at which you can extract natural gas right now.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.