Extinct Wolf-Sized Otter Had Powerful Bite That Likely Made It Top Predator

Otters are often thought of as cute, but the largest otters today are the giant otter and the sea otter, by size and weight respectively. And they would have both been outdone by Siamogale melilutra, an extinct otter species that lived six million years ago, researchers announced Thursday.

S. melilutra was likely the size of a wolf and lived in the wetlands of present-day southwest China, and its ecological niche in its habitat was likely that of a top predator. Compared to the top weight of about 100 pounds among the average adult male otters today, S. melilutra weighed in at 110 pounds.

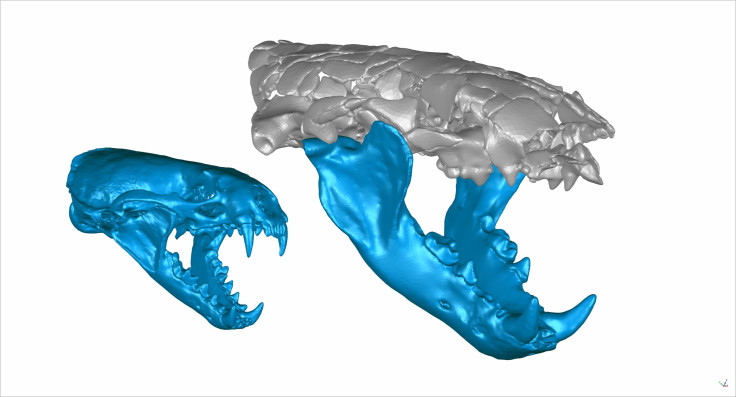

Researchers led by Z. Jack Tseng — an assistant professor at Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo — estimated the extinct animal’s size and weight based on CT scans of its fossils, which involved digitally reconstructing the cranium from a crushed fossil whose find was announced in January.

“We started our study with the idea that this otter was just a larger version of a sea otter or an African clawless otter in terms of chewing ability, that it would just be able to eat much larger things. That’s not what we found. We don’t know for sure, but we think that this otter was more of a top predator than living species of otters are. Our findings imply that Siamogale could crush much harder and larger prey than any living otter can,” Tseng said in a statement Thursday.

Simulations of S. melilutra’s bite and the strain it would cause to the jaws led the researchers to conclude that its jaw bones were much firmer than expected in an animal its size. The stiffness would mean it likely packed a pretty powerful bite. Even though the researchers don’t know what its likely diet was, its bite could easily crush the shells of big mollusks or bones or birds and small mammals.

“At the time that the otter lived, the area where its remains were found included a swamp or a shallow lake surrounded by evergreen forest or dense woodland. There was a diverse aquatic fauna at Shuitangba, including fish, crab, mollusks, turtles, and frogs, as well as many different species of water birds, all of which could have been potential prey for S. melilutra,” Denise F. Su, a paleoecologist at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and one of the leaders of the Shuitangba Project that discovered the fossil otter, said in the statement.

The researchers published a study Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports based on their findings. In the study, they also compared S. melilutra with extant otter species to better understand the extinct mammal. Of the 13 surviving otter species, the bending of the jaw bone of 10 species was compared to S. melilutra. This comparison showed a clear trend of smaller otters having sturdier jaws, except when it came to S. melilutra, whose jaws were found to be six times sturdier than expected.

“Carnivores are known to evolve powerful jaws, often for the purpose of cracking the bones of their prey. In the shallow swamp of South China, it’s possible that an abundance of big clams drove these giant otters to acquire their rare traits, including their crushing teeth and robust jaws,” Xiaoming Wang, a curator at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and part of Su’s team that discovered the otter fossil, said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.