French Court Jails Accomplices Over Charlie Hebdo Attack

A Paris court on Wednesday handed jail terms ranging from four years to life to more than a dozen people convicted of helping Islamist gunmen who attacked satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo and customers at a Jewish supermarket in January 2015.

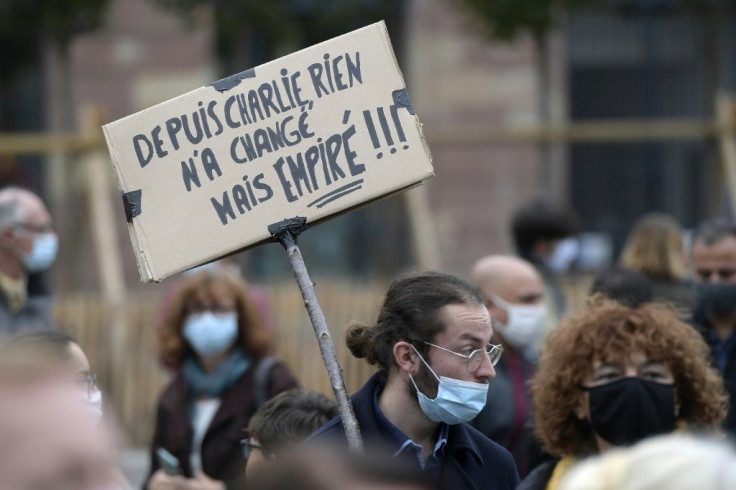

Survivors and family members of the dead sat in silence as the verdicts were read out, which they hailed afterwards as a victory for justice and freedom of speech after a sometimes traumatic trial that revived the horror of the killings.

The editor of Charlie Hebdo Laurent "Riss" Sourisseau, who lives under round-the-clock police protection, was also in court to hear the sentencing by a five-member team of magistrates who had listened to evidence against the accused over three months.

"It's been painful, searing. It's been a stage in our mourning process, necessary and unavoidable," said a lawyer for Charlie Hebdo, Richard Malka. "I hope it's the start of something else, of an awareness, a wake up call."

In the absence of the attackers themselves -- all three were killed by security forces in the days after their rampage -- French investigators instead focused on accomplices to the men, including their weapon suppliers.

The main accused, Ali Riza Polat, was judged to have known about his friend Amedy Coulibaly's plans to take part in the attacks, and was given a 30-year sentence for complicity, which he immediately said he would appeal.

Another 10 accused were present in court, all men ranging from 29 to 68 years old with prior criminal records but no terror convictions. They were all found guilty on a range of charges.

In all, 13 sentences were handed down, including to two accused who were tried in absentia: Hayat Boumeddiene, the partner of gunman Coulibaly, received a 30-year sentence, while Mohamed Belhoucine, a known Islamic extremist, was handed a life term.

Both of them are presumed to be in Syria and may be dead.

A fourteenth suspect was not sentenced because he was convicted in a separate terror trial earlier this year and is thought to dead.

During the attacks in January 2015, seventeen people were killed over three days, beginning with the massacre of 12 people at Charlie Hebdo magazine by brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi.

They said they were acting on behalf of Al-Qaeda to avenge Charlie Hebdo's decision to publish cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed, while Coulibaly had sworn loyalty to the Islamic State group.

Coulibaly was responsible for the murder of a French policewoman and a hostage-taking at a Hyper Cacher market in which four Jewish men were killed.

Those shot dead in the Charlie Hebdo office included some of France's most celebrated cartoonists such as Jean Cabut, known as Cabu, 76, Georges Wolinski, 80, and Stephane "Charb" Charbonnier, 47.

To mark the start of the trial on September 2, the fiercely anti-religion magazine defiantly republished the prophet cartoons, leading to a fresh violence and protests against France in many Muslim countries.

Three weeks later, a Pakistani man wounded two people outside the magazine's former offices, hacking at them with a cleaver.

On October 16, a young Chechen refugee beheaded teacher Samuel Paty who had showed some of the caricatures to his pupils.

And on October 29, three people were killed when a young Tunisian recently arrived in Europe went on a stabbing spree in a church in the Mediterranean city of Nice.

President Emmanuel Macron's government has introduced legislation to tackle radical Islamist activity in France, a bill that has stirred anger in some Muslim countries.

On the cover of its new issue published before the verdicts, Charlie Hebdo in typically provocative style published a picture of God being led away in a police van with the title "God put in his place".

"The cycle of violence, which had began in the offices of Charlie Hebdo, will finally be closed," editor Riss, who was badly injured in the attacks, wrote in an editorial.

"At least from the perspective of criminal law, because from a human one, the consequences will never be erased,," he added.

The Charlie Hebdo killings triggered a global outpouring of solidarity with France under the "I am Charlie" slogan and signalled the start of a wave of Islamist attacks around Europe.

Later that year, in November 2015, Paris was again besieged when Islamist gunmen went on the rampage at the Bataclan concert hall, the national stadium and at a host of bars and restaurants.

A trial of the only surviving gunman and suspected accomplices is expected to start in September next year.

Christophe Deloire, the head of press freedom group Reporters Without Borders (RSF), said he welcomed the verdict in court on Wednesday.

"It is proof that violent extremists don't have the last word. Thanks to justice, it is freedom that has the last word," he wrote on Twitter.

Patrick Klugman, lawyer for the victims at Hyper Cacher, said: "For most of the victims... I believe that they have feeling of having been heard."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.