How Fed Rate Hike Will Impact Africa: Ghana, South Africa, Angola Most Vulnerable With High Dollar Debt And Global Market Exposure

Thousands of miles and a vast ocean separate Africa from the United States. But the distance will not shield African nations from the U.S. Federal Reserve’s decision to raise its benchmark interest rate Wednesday after years of easy-money policies.

The announcement pushing the federal funds rate up a quarter of a point from the near-zero levels that had prevailed for seven years will strengthen the U.S. dollar and weaken just about every African currency. Some countries with ballooning debt and high exposure to global markets, such as Ghana, South Africa and Angola, will be most vulnerable, according to financial experts and analysts, while others, including Ethiopia and Ivory Coast, have buffers that may help them cope.

“It’s likely going to affect currencies across the board in most countries, and in sub-Saharan Africa quite dramatically,” said Anna Rosenberg, practice leader for sub-Saharan Africa at Frontier Strategy Group, a global research and advisory firm in Washington that specializes in doing business in emerging markets. “The moment your currency depreciates by 50 percent, your economy depreciates by 50 percent on paper. It knocks off a few billions on the economy overnight.”

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen said Wednesday continuing economic growth and the improving labor market contributed to the U.S. central banks's decision to lift the federal funds rate. The widely anticipated move signaled the Fed's confidence that the U.S. economy has significantly improved since the financial crisis of 2007-08. The new benchmark rate, which is what commercial banks pay to borrow from the Fed, will hover between 0.25 percent and 0.5 percent.

With its unsustainable domestic- and foreign-debt burdens, Ghana may be the hardest-hit African nation in the aftermath of the rate hike. The West African country’s debt-to-GDP level was 71 percent in June, and much of its debt is in the form of short-term, dollar-denominated bonds acquired over the past few years, which means Ghana will soon have to repay its debt in dollars. These debt payments will be even more expensive for Ghana following the Fed’s move. With oil revenue down 56 percent and the Ghana cedi currency losing value against the U.S. dollar this year, the country will struggle to come up with the money for these payments on its own, and lenders may not be willing to refinance the debt. Down the road, the Ghanaian government may be forced to default on its debt in the coming years.

“Ghana is quite vulnerable to a debt crisis,” said Judith Tyson, a research fellow specializing in financial market development for developing countries at the Overseas Development Institute, a London think tank. “The big issue is the fact they need to repay that debt in dollars.”

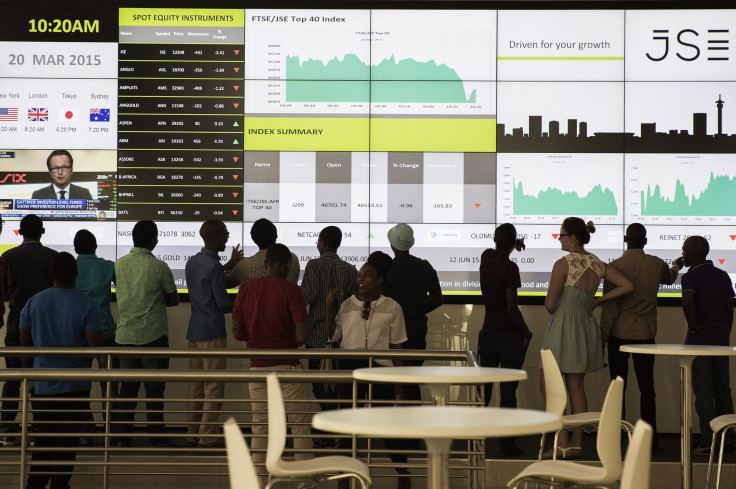

South Africa’s emerging-market economy, which is reeling from its own crisis, will also be among the most affected by increased interest rates, financial experts said. The mere prospect of a U.S. rate hike has drained capital from the country, with growth projected to be below 1.5 percent both this year and next, according to a recent report from the International Monetary Fund. South Africa’s rand has fallen more than 30 percent so far this year as investors have sold risky assets in anticipation of increased rates amid a commodity rout. The National Treasury said in its midterm budget in October that gross government debt will likely increase from 47.4 percent of GDP to 49 percent through 2016. Like Ghana, South Africa will pay the price for borrowing heavily in dollars when they were cheap as the U.S. currency strengthens from the increased rates. But unlike Ghana, South Africa has the advantage of less dollar-denominated debt.

“Most of the debt that we’ve accumulated is in local currency, so we do have that buffer,” said Lesibas Mothata, chief economist at Investment Solutions Ltd. in Johannesburg.

The U.S. rate hike will compound a number of factors already threatening Angola, the second-largest oil producer in Africa. Angola’s central bank has already stepped in at least twice this year to devalue the kwanza as much as 25 percent. Its commodity-linked currency will probably weaken even further against the dollar as the Fed raises rates for the first time in nine years and the price of oil — Angola’s main source of foreign exchange — plunges to the lowest level since 2008. The oil-dependent economy is also suffering from a slowdown in China, Angola’s top trading partner, as demand from Beijing declines. The southern African nation may struggle to pay for imports, which it heavily relies on for most food, industrial inputs and consumer items, financial analysts said.

“Angola will suffer extremely,” Rosenberg warned.

With its currencies pegged to the euro rather than the dollar, francophone Africa may fare the best on the continent in the aftermath of the Fed’s rate increase. Ivory Coast, for example, has issued few bonds denominated in foreign currencies, and the West African nation does not rely heavily on commodities, unlike many other economies on the continent. After years of civil unrest, the world’s top cocoa grower is enjoying a remarkable economic recovery and low inflation. The Ivorian economy has expanded by around 9 percent in each of the past three years under the leadership of President Alassane Ouattara, who won re-election in a landslide victory in October. It’s the largest economy in the eight-nation West African CFA franc currency zone.

Some nations in East Africa might also not be as vulnerable to the Fed's decision, financial analysts said. Ethiopia’s economy grew by 10.3 percent from 2013 to 2014 and has been ranked by the International Monetary Fund as one of the five fastest-growing economies in the world. This strong economic growth is expected to continue in 2015 and 2016. Ethiopia has suffered from devastating droughts and floods this year, leading to a surge in domestic food prices, but financial analysts said it does not have a stock exchange, which protects the economy from global movements such as interest rate hikes.

The Fed’s move Wednesday cast an ominous pall over the fate of many African economies. However, experts are confident that private investors will remain interested in Africa, even if turbulent times on the continent are ahead.

“They’re less fickle, and they’re willing to sit through market cycles,” Tyson said. “They’re much more focused on the long-term, and I think they still see Africa as an opportunity.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.