Indonesia's Indrawati Says Palm Oil Export Ban Will Hurt Other Countries, But Necessary

Indonesia's new palm oil export ban will hurt other countries but is necessary to try to bring down the soaring domestic price of cooking oil driven up by Russia's war in Ukraine, Indonesia's finance minister told Reuters on Friday.

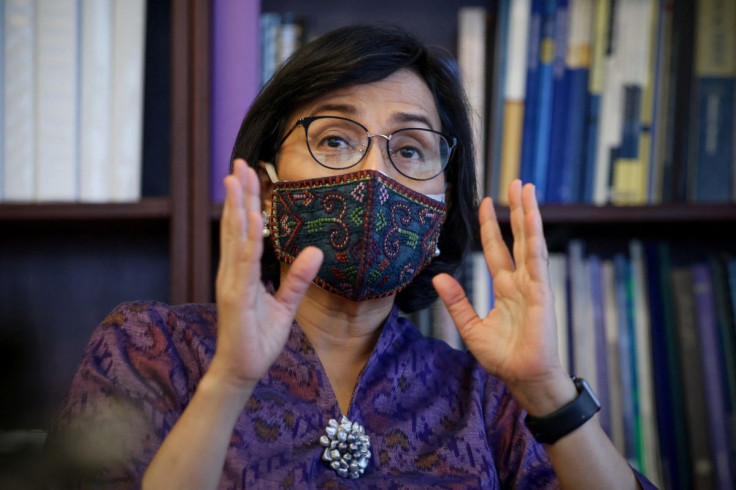

Sri Mulyani Indrawati said that with demand exceeding supplies, the ban announced earlier on Friday is "among the harshest moves" the government could take after previous measures failed to stabilize domestic prices.

"We know that this is not going to be the best result," for global supplies, she said in an interview on the sidelines of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank spring meetings. "If we are not going to export, that's definitely going to hit the other countries."

China and India are among big importers of palm oil from Indonesia, the world's largest producer accounting for more than half the world's supply. Palm oil is used in products from cooking oils to processed foods, cosmetics and biofuels.

Indrawati said previous measures requiring producers to reserve stocks for domestic use did not result in "the level of prices that we want. It's still too expensive for the ordinary household to buy those cooking oils."

At this week's meetings in Washington, policymakers have expressed concern about growing prospects of food shortages due to the war in Ukraine, a major producer of wheat, corn and sunflower oil. World Bank President David Malpass said repeatedly that countries should avoid hoarding of food stocks, export controls and other trade barriers to food.

COUNTRY NEEDS FIRST

But Indrawati, a former World Bank managing director, said that as a political leader and policy maker food security issues needed to be defined first at the country level, then regionally and globally.

She likened the current food supply situation to the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, when countries competed with each other for masks, medical protective gear and other critical supplies.

"Just like we were facing during the pandemic, we know this is not good in the medium and long term, but in the short term, you cannot stand in front of your people when you have the commodity which is needed by your people and you let (supplies) just go out" of the country.

Indonesia's move, which takes effect on April 28, caused prices of alternative vegetable oils to surge, with soybean oil hitting a record high on Friday. An Indian trade group called the ban "rather unfortunate and totally unexpected."

Indrawati said her government would analyze the impact of the measure on global and regional market dynamics.

For palm oil and other food commodities, she said the World Bank and other international institutions needed to focus on "supply side measures" to increase production.

But Indrawati said Indonesia has limited ability to increase palm oil production due to environmental concerns. Since 2018, the government stopped issuing new permits for palm oil plantations, which are often blamed for deforestation and destroying habitats of endangered animals such as orangutans.

Instead, Indonesia was focusing on improving infrastructure to allow producers to become more efficient and increasing production of other crops in high demand, including corn and soybeans, she said.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.