Japan Prepares For Dangerous Operation Removing Fuel Rods At Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant; Full Decommissioning Could Take Decades

Japan’s crippled Fukushima Daiichi facility is getting ready to remove nuclear fuel rods from the plant’s wrecked reactors, in one of the most dangerous and risky operations that are part of a long and arduous journey toward decommissioning the plant.

The nuclear power plant was hit by a giant tsunami triggered by an earthquake in March 2011, which ravaged the facility and damaged its back-up generators and cooling system. A power supply failure damaged the reactors at Unit 1, Unit 2 and Unit 3, leading to their partial meltdown. And now, engineers are preparing to remove fuel rods from a storage pool inside the plant’s Unit 4 reactor in batches, in a technically tricky operation, and transfer them to a common pool with better safety precautions.

"It's going to be very difficult but it has to happen," an official at the facility told BBC.

Unit 4 was not in operation at the time the tsunami hit the facility and hence all of its fuel rods were in the storage pool. However, hydrogen from Unit 3 escaped into Unit 4, causing an explosion that tore off its roof.

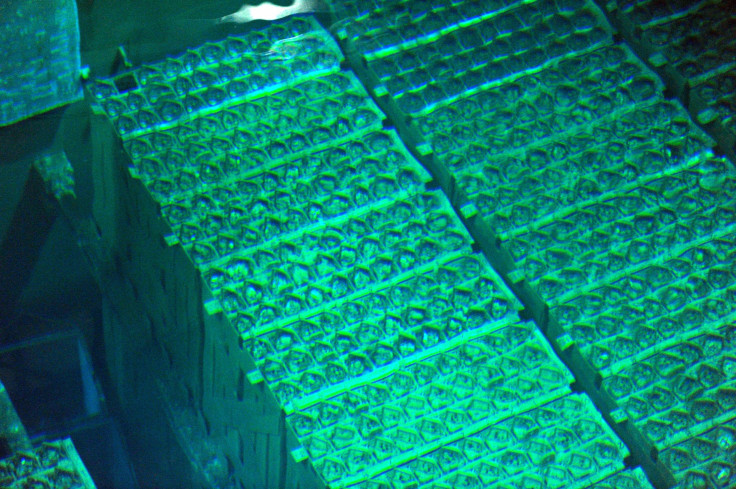

The storage pool in Unit 4 currently has more than 1,000 uranium and plutonium fuel rods, most of which are spent, but their present condition is unknown and experts fear some of the rods may have been damaged in the explosion.

The fuel rods are four-meter long tubes and are always kept submerged in water to avoid contact with the atmosphere to prevent their overheating and meltdown, which could lead to radioactive contamination of the surrounding areas.

"Inspections by camera show that the rods look OK but we're not sure if they're damaged - you never know," a senior official told BBC.

Elaborate precautions have been taken by the plant’s beleaguered operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, or Tepco, which has been accused of mismanaging the decommissioning process at the crippled plant.

"It is crucial. It is a first big step towards decommissioning the reactors," Tepco spokesperson Mayumi Yoshida said, according to an Agence France-Presse report. "Being fully aware of risks, we are determined to go ahead with operations cautiously and securely."

The Process

Most of the debris that fell into the pool after the blast has since been removed and a safety hood has been erected above the building to contain any possible radiation leaks, Tepco said.

Now, engineers are planning to shift the fuel rods in batches of 22, using a new crane installed at the facility. The rods will be encased in a watertight cask to prevent their contact with air, before being lifted away by the crane.

A remotely-controlled machine will lift and place the fuel rods weighing about 300 kilograms each in to a cask kept submerged in the pool. The watertight cask -- weighing about 91 tons -- will then be pulled out of the water using the crane and transported to a new pool.

The process will be reversed there and the rods could remain in the new storage facility until the decommissioning process is completed.

Tepco has demonstrated the process in a video link here.

Risks

Experts are wary of the risks involved in the process and even minor errors could lead to contamination and jeopardize the entire decommissioning process.

"Any trouble in this operation will considerably affect the timetable for the entire project," Hiroshi Miyano, a nuclear systems expert, told AFP. "This is an operation TEPCO cannot afford to bungle."

Tepco has claimed that it has taken every possible safety precaution and has made back-up arrangements to account for the possibility of a power failure and the accidental slipping of the cask during the operation.

Tepco has not specified an exact date for the transfer of the rods, but has said that shifting of each batch of rods could take more than a week.

The entire decommissioning process is expected to take decades as several setbacks and accidents, such as multiple leaks of radioactive water from the facility, have delayed the process.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.