'Kick And Kill' Strategy Takes First Step Toward An HIV Cure

In what might potentially be the first step toward developing a lasting cure for HIV, Danish researchers on Tuesday revealed what has been hailed as a breakthrough discovery that exposes the virus to the natural defenses of the immune system, the Guardian reported Tuesday.

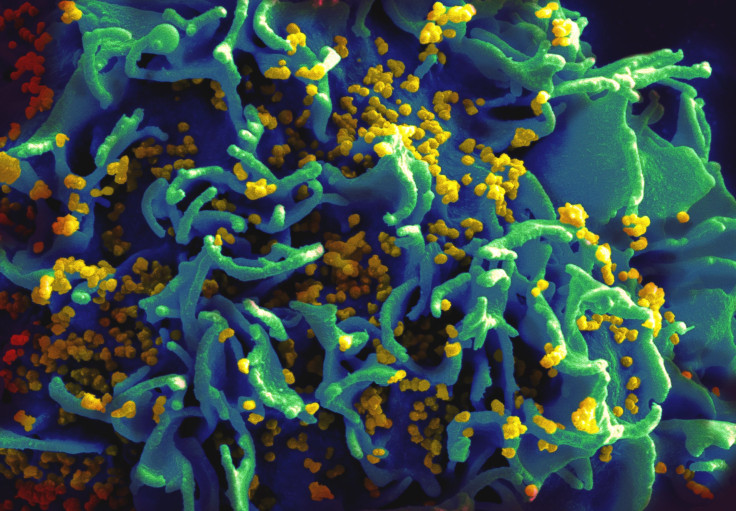

A Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV, infects CD4 cells, which are an essential part of the body’s immune system. This makes the task of eliminating them almost impossible, as the “killer” T-cells, which are responsible for attacking and eliminating pathogens in the blood stream, can’t detect the virus hidden in the CD4 cells.

Anti-Retroviral Therapy, or ART, which basically involves using a cocktail of drugs to suppress the virus, has so far failed to completely eliminate it. As a result, patients on ART often continue to have an almost undetectable level of HIV in their system. This hidden reservoir of the virus, undetectable through current screening techniques, is responsible for a return of the disease once the patient stops the therapy, and has ensured that cures and vaccines for AIDS have so far remained elusive.

The results revealed Tuesday, at the 20th International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, were drawn out of a pilot study conducted by researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark.

The research team, led by Ole Schmeltz Sogaard -- a senior researcher in the department of infectious diseases at the university -- used anti-cancer drug Romidepsin to activate the virus and bring it out of hiding. This process exposed the virus to the T-cells and made them vulnerable to a direct attack.

“This is a two-step system where we bring the cells to the surface and then rely on the immune system to kill them,” Sogaard told reporters in Melbourne.

However, the pilot study, which involved six patients who were given three doses of Romidepsin over three weeks, found that while the immune system detected the exposed viruses, it did not attack them.

“That’s what we are focusing on in the next study,” Sogaard said. “We will teach and prime the immune system to recognize HIV before we give patients the cancer drug and we hope there will be a better chance the immune system can clear those cells when the HIV is reactivated.”

The latest development comes just a few days after doctors at the University of Mississippi announced that a baby -- christened the “Mississippi baby” -- which they thought had been functionally cured of HIV through treatment by a combination of anti-retroviral drugs, now had detectable levels of virus in her bloodstream.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.