Magnetic Field Around Black Hole V404 CYGNI Much Weaker Than Estimated

Black holes notoriously devour any planetary body that dare cross their paths. Their intense gravitational pull and eerily omnipotent space presence made them a science fiction staple and the most fascinating phenomenon in the dark expanse of space.

Their incredible appetite for rocks and stars in space is well known. The world in and around a black hole is said to be a physics-bending, time-warping highly charged area that is much too choppy, treacherous and risky for exploration.

They come in a range of sizes from slightly larger than our sun to the size of our solar system. These supermassive black holes are thought to lie at the heart of all massive galaxies and are likely to play a decisive role in the formation and evolution of galaxies.

There are also tiny black holes that are slightly bigger than our sun but contained in a small area. They form in the death of massive stars or the merger of neutron stars or a neutron star colliding with another stellar black hole. When they merge, they are known to even produce gravitational waves.

But as it turns out, black holes might not be the pumped-up space void looking to consume all.

A team of scientists from the University of Florida (UF) have been studying them and have published a paper in the journal Science on Friday that states these tears in the fabric of the universe have significantly weaker magnetic fields than previously thought.

On observing a 40-mile-wide black hole that is at a distance of 8,000 light years from Earth called the V404 Cygni, the team were able to make the startling find. On measuring the magnetic field that surrounds the deepest wells of gravity in the universe, the authors found that it was around 400 times lower around the V404 Cygni than previously estimated.

Though previous estimates were low quality and crude, scientists have been baffled by the extent of over estimation. The feared magnetic field around a black hole that can pull you into a void where time ceases to exist the way we experience it, a point of no return from which even light cannot escape is weaker than was previously thought.

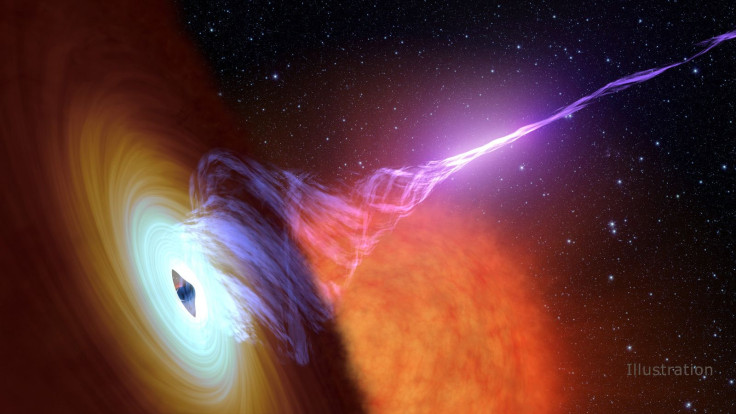

Trying to understand how matter behaves under the most extreme conditions, scientists studied the "jets" of particles that shoot out of the black holes’ magnetic field at nearly the speed of light, while all other particles is sucked into their abysses.

"The question is, how do you do that?" co-author Stephen Eikenberry, a professor of astronomy in UF's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences said in a press release on their website. "Our surprisingly low measurements will force new constraints on theoretical models that previously focused on strong magnetic fields accelerating and directing the jet flows. We weren't expecting this, so it changes much of what we thought we knew."

The team used measurements from data collected in 2015 during a black hole's rare outburst of jets. The event was observed through the lens mirror of the 34-foot Gran Telescopio Canarias, the world's largest telescope, co-owned by UF and located in Spain's Canary Islands.

These outbursts occur suddenly and are short-lived, said study lead author Yigit Dalilar and co-author Alan Garner, doctoral students in UF's astronomy department. The 2015 outbursts of V404 Cygni lasted only a couple of weeks. The previous time the same black hole had a similar episode was in 1989.

"To observe it was something that happens once or twice in one's career," Dalilar said. "This discovery puts us one step closer to understanding how the universe works."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.