Man Vs. Machine: Cambridge University To Launch Center For The Study Of Existential Risk

Come to Cambridge University if you want to live.

If all goes according to plan, the venerable British institution will soon be home to the Center for the Study of Existential Risk, a multidisciplinary research center that will focus on issues that pose a threat to humanity.

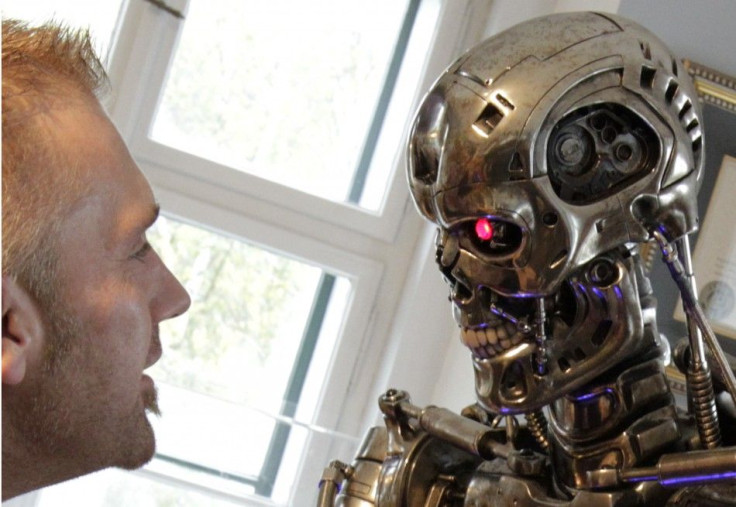

The center will investigate a wide range of apocalyptic scenarios, ranging from runaway nanotechnology to extreme weather events caused by climate change to the rise of superintelligent and hostile artificial intelligence. Basically, if it can appear in a science fiction or a Michael Bay film, it's fair game.

“Our goal is to steer a small fraction of Cambridge's great intellectual resources, and of the reputation built on its past and present scientific pre-eminence, to the task of ensuring that our own species has a long-term future,” the founders wrote in April.

The architects of this doomsday academy are Cambridge philosopher Huw Price, Cambridge cosmology and astrophysics professor Martin Rees, and Skype founder Jaan Tallinn.

In August, Price and Tallinn wrote a piece for The Conversation speculating on the dangerous possibilities of artificial intelligence.

Computers can already play chess better than humans, and it seems almost inevitable that machines will continue to improve in analytical power until they match -- and likely exceed -- the capacity of the human brain. But beating people at chess, while a bit wounding to the ego of our species, isn't exactly threatening.

However, “the greatest concerns stem from the possibility that computers might take over domains that are critical to controlling the speed and direction of technological progress itself,” Price and Tallinn wrote.

If machines surpass humans in the ability to write computer programs, there could be an “intelligence explosion.” Humanity would no longer be in the driver's seat of technological progress, and we could only marvel at what the machines make.

While one could hope that a smart machine wouldn't necessarily be hostile, there's no guarantee that they would even take notice of humans, let alone work with them or be kind to them.

Wary pessimists say that “almost all the things we humans value (love, happiness, even survival) are important to us because we have particular evolutionary history -- a history we share with higher animals, but not with computer programs, such as artificial intelligences,” the pair wrote.

If the machines take over, even if there is no conflict between us and them, humans will still have to deal with the hard fact of losing our place at the top of the pyramid. But there is no current framework for investigating or formulating a plan to deal with this shift.

“A good first step, we think, would be to stop treating intelligent machines as the stuff of science fiction, and start thinking of them as a part of the reality that we or our descendants may actually confront, sooner or later,” Price and Tallinn say.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.