Medicaid In Florida: State's Refusal To Expand Health Program Jeopardizes Health Care For 800,000, And Maybe Millions More

Every Friday morning, Mayra Cruz Rivera swallows seven pills of methotrexate at once. The chemotherapy drugs immediately leave a hard metallic taste in her mouth, and her body doesn’t like them -- she throws up a lot, and lately she’s been having seizures, plus other problems. But it’s all she can do to treat her lupus, a devastating autoimmune disease, because she doesn’t have health insurance.

Cruz Rivera, 47, was diagnosed with lupus in November 2006. It worsened in 2008, so the Winter Springs, Florida, resident began chemotherapy, which made her horribly sick. By August 2013, the treatments made her so ill that she was forced to quit her job at a public school, which she had kept for the health insurance benefits. Her husband is unemployed, and she said her application for Medicaid has been denied -- twice.

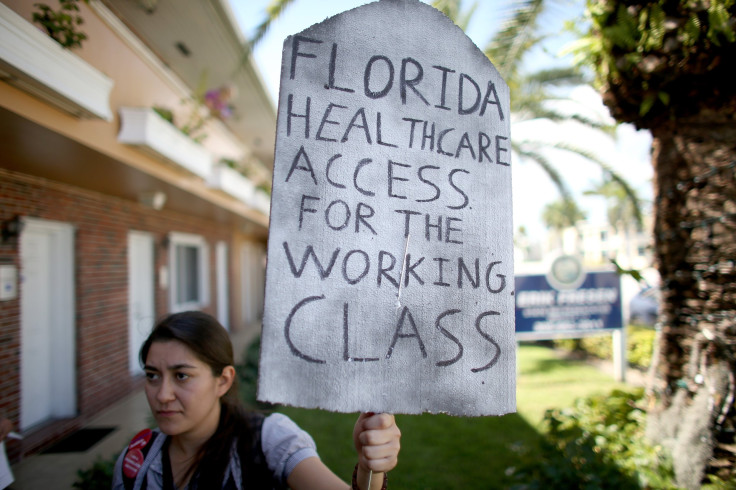

In the Sunshine State, the question of health care coverage for people like Cruz Rivera has sparked a bitter and even dramatic monthslong controversy that culminated this week. On Tuesday, the state Legislature’s debate over whether Florida would expand its Medicaid program all but ended when the House abruptly adjourned its session. Gov. Rick Scott filed a lawsuit against the federal government for, he charged, trying to illegally "coerce" the state into expanding Medicaid. At stake but lost in the melodrama were billions of dollars in healthcare funding for real people with actual health problems, say local medical providers, who fear that the longer Florida refuses to grant impoverished residents health care coverage, the more lives will be at risk.

Scott made his fortune in the healthcare sector, where he once presided over Columbia/HCA, a major for-profit company. He resigned in 1997 after it was investigated for what the Justice Department ultimately deemed the “largest health care fraud case in U.S. history,” which included attempting to falsely bill Medicare. Scott was never charged in the case but was generously compensated after he resigned from the company.

“Here in Florida, they let you die,” said Cruz Rivera, who added that she has explored every option she can think of to get health insurance, to no avail. She currently depends on clinic near her central Florida home for free X-rays and blood tests. But she knows she can’t keep going there forever. She said she needs surgeries, because her organs are breaking down from the chemo. “I don’t have time to wait,” she said. “I need the insurance now.”

But it’s unlikely she’ll get it. Worse yet, the free care on which she’s been relying could be jeopardized as well. Not only has the Legislature all but killed the possibility of expanding Medicaid, but Florida might also lose additional federal funding, called a low-income pool, designated for patients who don’t have insurance or can’t afford to pay for doctors and medical tests.

Getting Hit Twice

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, overhauled the American healthcare landscape in several ways. One of them was by giving states money to expand Medicaid -- government health insurance for people with low incomes -- by raising the ceiling for eligibility to 138 percent of the federal poverty line, currently $16,105 for an individual or $32,913 for a family of four.

The catch is that in 2012, the Supreme Court made expanding Medicaid optional for states. To date, 29 states plus the District of Columbia have done so -- Montana became the most recent convert after Gov. Steve Bullock approved the measure Wednesday. But 21 states, including Florida, have not. In those states, some residents earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, at least under the old rules. But they make too little to afford other forms of health insurance, sending them spiraling into what is often called the health insurance gap.

In Florida, there are 800,000 of these people, out of about 3.6 million uninsured overall. Although the state Senate has supported expanding Medicaid to cover those who fall into the gap, the House has not. When that body ended its session Tuesday, three days early, it all but killed the chances of coming to an agreement with the Senate in order to expand Medicaid.

“I would say there’s probably very little chance,” said Michael Williams, spokesman for Florida House Speaker Steve Crisafulli. Crisafulli, who opposes expansion, has written that Medicaid is a “broken system” that has “no incentive for personal responsibility for those who are able to provide for themselves.”

But the decision not to expand Medicaid has implications for another source of funding, which is crucial for low-income Floridians who don't fit the usual image of someone in need of free or government-sponsored medical care. “The face of the uninsured has been stereotyped to this working poor, possibly homeless, not wanting to invest in themselves, to lift themselves up,” said Marni Stahlman, president and CEO of Shepherd’s Hope, the clinic that Cruz Rivera visits. Shepherd’s Hope saw 21,000 patients last year, and Stahlman expects that number to rise this year.

Even as more patients depend on them, places offering free care may have fewer and fewer resources to help them. In a letter dated April 14, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS, for short, told Florida health officials that whether or not the state expanded Medicaid was “an important consideration” when it came to whether CMS would continue to fund the low-income pool, a $2.2 billion fund set to expire at the end of June.

It’s not clear, at this point, how that particular fund will be affected by Florida’s failure to expand Medicaid. Aaron Albright, a spokesman for CMS, pointed out that Florida is not the only state whose low-income pool was being reviewed, and that such funding was not contingent upon whether a state expanded Medicaid. Nevertheless, he added that low-income pool “funding should not pay for costs that would be covered in a Medicaid expansion.”

A 'Perfect Storm'

Last year, the faith-based nonprofit Florida Hospital group in the central part of the state received $90 million from the low-income pool to help cover $200 million in costs to treat patients who could not afford treatment, according to Michael Griffin, its vice president of public affairs. And the remaining $110 million? That amount ends up being redistributed to privately insured patients -- and their insurers or employers -- who can pay. As a result, on average, insured patients pay 8 percent more than they would if more people were insured, Griffin said.

“It’s just fundamental economics. If we had more people with insurance, we would have to swallow less money,” Griffin said. He argued that Florida is particularly ill-equipped to force privately insured patients to share the costs of treating the uninsured, because there are so few patients that do have private insurance, and so many that do not. “It’s kind of a perfect storm,” he said.

In Florida, 41 percent of residents have health insurance through their employers -- a tie for third-lowest in the country. Five percent carry other forms of private insurance. Meanwhile, the 17 percent of Floridians insured by Medicare, government insurance for seniors onto whom costs cannot be shifted, tied for fourth-highest in the U.S. And overall, 19 percent of Floridians have no insurance at all. Only Texas and Nevada have higher rates of uninsured people.

Recently, in March and April, Cruz Rivera was forced to spend time in the hospital. But she couldn’t concentrate on getting better, she said, because she was instead trying to persuade nurses and doctors not to give her medical tests, because she didn’t have the insurance to pay for them.

“No, I’m not having these tests done,” she remembered trying to say. “I told them, ‘Send me home.’”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.