This Mysterious Disease In Canada Is Causing Hallucinations, Over 40 Affected

KEY POINTS

- Residents of a Canadian province learned of a mystery disease through a leaked memo

- Public officials have been tracking a cluster of 43 reported cases of the condition for over a year

- Experts are still investigating what may be causing the mystery disease

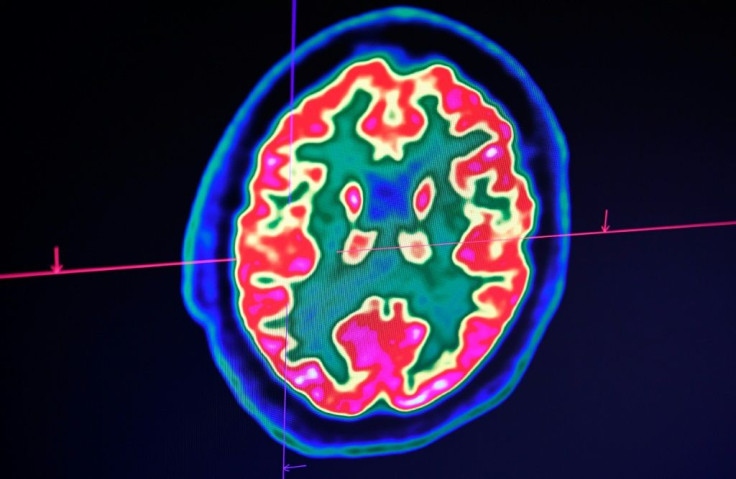

A mysterious disease causing symptoms resembling those in a rare and deadly brain disease, including spasms and hallucinations, has affected over 40 people in a province in Canada.

New Brunswick could be dealing with a mysterious brain disease similar to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), a rare and fatal prion disease. Public health officials confirmed that a cluster of about 43 cases of the unknown condition is being tracked for more than a year.

It was through a leaked memo last week that residents in the Canadian province first learned of the investigation, The Guardian reported. In the memo, public health officials are urging doctors and nurses to be on the lookout for symptoms similar to that of CJD.

"We are collaborating with different national groups and experts; however, no clear cause has been identified at this time," the memo further noted.

Mysterious Symptoms

According to Dr. Alier Marrero of Moncton's Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont University Hospital Centre, who is leading the investigation on the cases, patients first complain of pains, behavioral changes and spasms.

While early symptoms may be chalked up to known conditions such as anxiety or depression, patients begin to present other symptoms within 18 to 36 months. This time, patients may experience muscle wasting, drooling, cognitive decline and teeth chattering. Some even reported having hallucinations, such as feeling like insects were crawling on their skin.

While some of the symptoms, such as memory loss and abnormal movements, were quite similar to that of CJD, it is worth noting that testing has not confirmed any CJD cases so far.

The first case of the mysterious brain disease was detected in 2015, the memo noted. At the time, it was the only known case. However, 11 new cases of the mysterious condition emerged in 2019 and 24 in 2020. There have been six cases in 2021, CBC News said, and it's believed that five people have died from it.

The mysterious illness affects people of all ages. The majority of the cases have been linked to the Acadian peninsula, which The Guardian noted to be a "sparsely populated" region in the province.

Known Or Unknown Diseases

The team of experts is now racing to determine exactly what is causing the illness, whether it's because of a known syndrome or a new one. They're also looking at the possibility that it has environmental origins, such as from insects, the water or even plants.

"We don't know what is causing it," Marrero said, The Guardian reported. "At this time we only have more patients appearing to have this syndrome."

So far, Marrero added, there is no evidence suggesting that it's a prion disease. Preliminary data also suggests that it is not genetic, CBC News reported. But he has also pointed out in an interview with Medscape Medical News that the cause may be environmental.

"We have not yet been able to come up with causative agent, except that everything that we have analyzed so far suggests this is an environmental exposure of some kind that is acquired through food, water, air, professional activities, or leisure activities," he told the outlet.

Marrero also further noted that the cases appear to have a "geographical clustering."

More Questions Than Answers

News of the mysterious disease naturally prompted concern among the residents. Politicians in the province have also demanded answers, The Guardian reported. However, investigation on the illness is still ongoing.

"At this point, we have more questions than answers," Chief Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Jennifer Russell, said, according to CBC News.

Experts have since cautioned people against making premature conclusions and urged the public not to panic.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.