Pew Report Presses Regulators On 'Unaffordable' Car Title Loans And Payday Lending Problems

Paula Odrick was in a Philadelphia salon last summer, getting her hair done before heading to a religious convention, when her car disappeared. She asked around the neighborhood and phoned the local transportation department to see if they’d towed it -- she’d parked near a bus stop -- before she finally called the police and learned that someone with a tow truck had repossessed her 2005 Toyota Corolla, which was the collateral she’d put up for a $1,500 auto title loan three years prior.

She had already paid more than $4,000 on that loan -- and a refinancing. The sum she borrowed had once offered a brief respite from mounting bills. Odrick lost her job as an administrative secretary at a financial services firm after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Years spent in and out of work took a toll on her finances. The terms of the auto title loan, as she understood them, seemed affordable at first, then increasingly nightmarish.

"They were sucking the life out of me," Odrick says. "Everything was tied up in this one bill."

As federal regulators prepare rules regarding high-cost storefront payday loans -- a topic President Obama is expected to address Thursday in Birmingham, Alabama -- consumer advocates are pressing for regulations that would apply to a broader landscape of loan products that they call debt traps, including online payday loans (not just storefronts) as well as auto title loans such as the one that plagued Odrick.

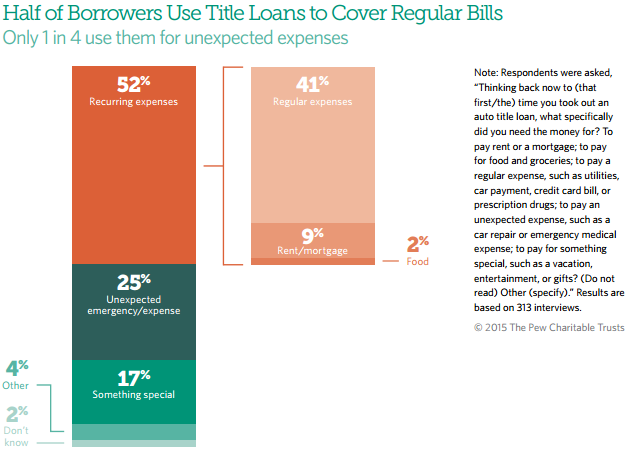

“Auto title lenders have a tremendous amount of leverage over borrowers,” Nick Bourke, the lead author of a new Pew Charitable Trusts report on the topic published today, says. More than 2 million Americans a year pay $3 billion in car title loan fees, according to the findings. About half the borrowers that Pew surveyed said they took out the loans to cover everyday expenses such as rent and utilities.

The research comes just ahead of a field hearing that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) will host about payday lending on Thursday in Richmond, Virginia. It’s the type of event the agency typically uses to anchor big announcements on regulatory matters.

“One reason why the CFPB rules are so important is because they really have to set the scene for what comes next in the small-dollar loan market,” Bourke says.

Similar to payday loans, auto title loans typically come with triple-digit interest rates. The CFPB can’t regulate those interest rates, but the agency could design rules around other areas that consumer advocates say would make the loans more manageable and less likely to lock borrowers in a cycle of debt.

For instance, the agency could require lenders to account for a borrower’s ability to repay the loan, thereby ensuring smaller payments that could be spread evenly across the life of the loan. “The best way to accomplish this is to limit payments to an affordable percentage of a borrower’s income,” Bourke says.

The study, which included a national survey of 313 borrowers, found that borrowers earn a gross median annual income just shy of $30,000, or about $2,500 a month.

The average $1,000 car title loan would eat up half the typical borrower’s monthly income. A loan that size, “with a typical $250 fee requires a lump-sum payment of $1,250 after 30 days,” according to the report, “far more than most borrowers can afford.”

To keep up, borrowers often renew the loans. In Tennessee, for example, “approximately 84 percent of all title loans are renewals,” the report says.

Or, to pay off and exit the loan, nearly half the survey respondents (47 percent) had to seek a “cash infusion” from another source, such as tax refund, friends and family, or a loan from a bank or credit union.

“When you make a loan to someone who can’t afford to repay it, you’re getting repayment based on some sort of abusive thing,” Jay Speer, executive director of the Virginia Poverty Law Center in Richmond, says. With payday loans, lenders hang on to a signed check from a borrower or get access to their bank accounts. With title loans, of course, borrowers sign over a lien on the car.

Lenders “have this power over you which they use to get you into what we refer to as a debt trap,” Speer says.

The law center’s “predatory loan hotline” has fielded calls from about 600 borrowers over the past five years. While a state law passed in 2008 dramatically reduced the number of storefront payday loan shops, Speer says, borrowers these days call mostly about online payday loans and car title loans.

Each year, cars are repossessed from between 6 percent and 11 percent of title loan borrowers, the Pew report finds. One-third of all borrowers only have access to one working car.

“Repossessions are pretty devastating to people,” Philadelphia-based attorney Robert Salvin, who specializes in consumer debt, says. “You wake up in the morning, and your car’s not there. How do you get to work? How do you get a new car?”

Salvin is representing Paula Odrick in a lawsuit against two third parties she says were involved in repossessing her Corolla. Odrick can’t sue the title lender, because of an arbitration clause in the contract that prohibits her from doing so.

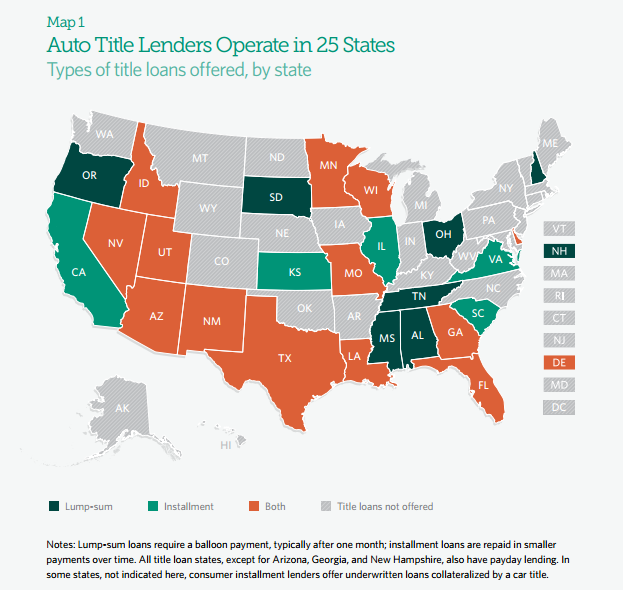

Half the states in the U.S. -- including Odrick's home state of Pennsylvania -- don’t permit high-interest title lending. When she took out the loan in 2011, she drove to neighboring Delaware. She was certain she’d be able to pay it back and, in the meantime, have breathing room to deal with expenses as she worked full time and studied for a bachelor’s degree.

Instead, Odrick says, the loan terms were never made clear to her, and her payments didn’t make a dent in what she owed -- “like I was in quicksand,” she adds. Odrick began to feel as though “they didn’t want you to pay it off,” she says. “They wanted your car.”

At one point, Odrick filed for bankruptcy, but the bankruptcy was dismissed. After that, she began to work out payment arrangements with various creditors. But for nearly two years, she hadn’t heard from the car title lender -- that is, not until the day her car, valued at over $6,000, was repossessed.

For months, she took public transit to and from her nightshifts at a local hospital. She’d sometimes arrive at work hours early and sleep there before her shift started, for fear of being late.

Odrick finally bought another car in November. What she still doesn’t understand is how regulators allow “organizations like this to continue to do business,” she says. “Why hasn’t anything been done?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.