Does Money Buy Votes? Most Americans Say Yes; A New Study Says They’re Right

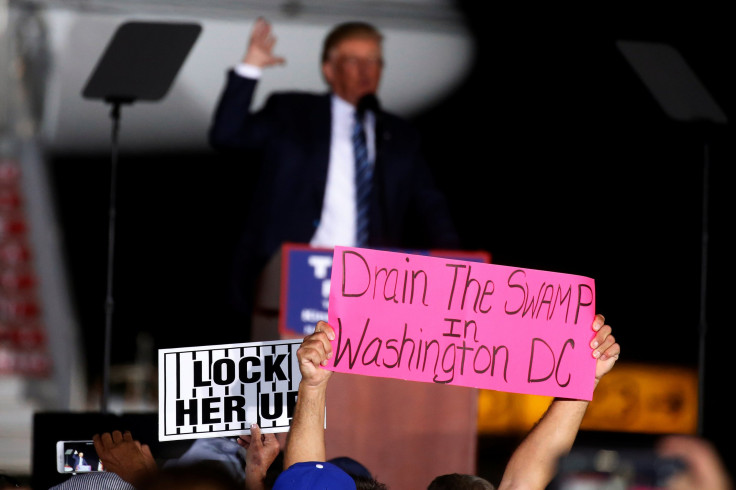

For politicians, decrying money’s influence in politics is almost always a safe bet. Much of Donald Trump’s and Bernie Sanders’ appeal in last year’s presidential election came from their attacks on money in Washington, D.C., with Trump promising to “drain the swamp” when elected. Overwhelming majorities consistently affirm to pollsters a belief that money has a corrupting effect on the U.S. government. But few have been able to precisely quantify that corrupting effect and measure how much money it takes to move congressional votes. Until now.

Because there are so many factors and variables influencing political decisions, researchers have found it difficult to prove causation between campaign money and congressional votes. But in a new study, researchers led by Thomas Ferguson believe they found a group of public officials that illustrates money’s impact: Democrats who changed their mind about Dodd-Frank.

Ferguson and his team assert that they were able to document exactly how the finance industry, which lobbied heavily to undo parts of the historic 2010 law, was able to spend money to increase the chances that House Democrats would vote to undo legislation they previously supported.

As a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Ferguson has written extensively about money in politics and gave an eerily prescient prediction about American politics in 2014. He says the new study refutes the notion -- advanced for years by academic political science research -- that money doesn’t have much influence on the outcome of political campaigns or the decisions of politicians when in office, a conclusion that Ferguson thinks has been driven by a combination of bad analytical methods and an allegiance to the status quo which funds research grants and keeps academics employed.

“It is certainly the case that the academic work on money and politics is mostly pretty bad. It’s often, frankly, embarrassing. When I was in grad school they just kept telling me it didn’t matter at all,” Ferguson told International Business Times. “You’re living in a money driven political system, and the average political scientist is like a fish who doesn’t realize they live in water.”

The researchers chose to look at Dodd-Frank because it produced very clear allegiances. Wall Street and the financial industry opposed it, as did Republicans. But some Democrats switched sides during the course of five different votes about parts of the bill between 2013 and 2015.

“You could see the way Dodd-Frank and the battle to repeal it became like the 30 Years War. It was the banking community vs. the legislature. It was a crusade,” Ferguson told IBT.

The researchers found that for every $100,000 the financial industry spent on campaign contributions for a House Democrat who voted for Dodd-Frank, they were able to increase the likelihood that same Democrat would vote to dismantle parts of the bill by 13.9 percent, according to the study.

Democratic representatives who voted in favor of dismantling Dodd-Frank often received $200,000 to $300,000 from the industry. The average House member raised $1.6 million for the 2012 campaign, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

“Our results show that financial sector money played a substantial role in weakening Dodd-Frank among once-friendly Democrats,” Ferguson and co-authors Paul Jorgensen and Jie Chen write in the study, which was published by the Roosevelt Institute on Tuesday.

By tracking the relationship between the money the financial industry spent on dismantling Dodd-Frank, as well as differences between the way Democrats voted over time, the team was able to narrow down the variables affecting the votes, since most of the situation stayed the same.

“Same people, same districts,” Ferguson said. “Big change was implausible... the big thing that varied over time was money.”

Ferguson’s team tried to eliminate other variables as well. For example, they found that margin of victory in the previous election was not a predictor of whether Democratic lawmakers broke ranks to vote on behalf of the financial industry. However, they found that the chances of a Democrat breaking with the party went up by 90 percent if the lawmaker served on the House Financial Services Committee.

While one could argue that this indicates Democrats who knew more about the industry were more likely to vote for undoing financial regulations, Ferguson has a more cynical interpretation. He points to research published last year by the Institute for New Economic Thinking that found that members of Congress take out more loans with more favorable interest rates when they are appointed to finance committees, a pattern that doesn’t appear across Congress generally. The trend is present only for legislators serving on committees responsible for overseeing the industry that hands out loans. The research dovetails with another study published last year that showed lawmakers who owned bank stocks were much more likely to vote for the 2008 bailout.

It is certainly possible that some lawmakers might have believed a bill was a good idea before it was enacted and changed their view after the legislation built a real-world track record. Also, the financial industry did not try to persuade lawmakers of the perils of Dodd-Frank with just campaign cash -- Wall Street firms also spent big on lobbying and public relations campaigns designed to vilify the legislation.

Still, the study’s other findings bolster the view that money was the decisive factor.

The researchers found that Democrats who were leaving the House at the end of their term were three times more likely to vote on in favor of the finance industry.

“It is sort of grimly humorous or might make you want to throw up, depending on how you look at it,” Ferguson said. “Many of them are leaving because they want to cash out. In a few cases they were running for Senate and needed to raise a ton of money.”

Researchers also looked at campaign cash’s influence in the early fight over net neutrality, a battle which aligns large content providers, like Netflix or Google, with Democrats who want net neutrality, against Republicans and internet service providers like Comcast and Time Warner, who oppose it.

Specifically, the team looked at a 2006 bill that would have prevented the creation of a two-tiered internet and found that every $1,000 spent by firms in favor of net neutrality decreased the odds of a vote against net neutrality by 24 percent, and every $1,000 spent by companies against net neutrality increased the chances of a vote against the amendment by 2.6 percent.

While the research just looked at two specific issues, it’s that kind of granularity that is necessary to eliminate what Ferguson describes as the “excuses” given by researchers who say there is no clear evidence that campaign contributions affect policy. If spending money on politicians’ campaigns didn’t help get desired outcomes, people and corporate entities wouldn’t do it, he said.

According to Ferguson, part of the reason why research on influence is lacking is because data on campaign spending is often incomplete. He notes that the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and the IRS have separate systems for monitoring campaign spending.

“A serious government that wanted transparency would unify these systems,” Ferguson said.

But it’s not just the money that’s opaque to the outside world, it’s the negotiations that happen in Congress as well, according to Thomas Stratmann, a professor of economics and law at George Mason. Stratmann notes that studying how influence works in Washington requires data, and where the data exists are precisely the areas where politicians are most likely to be careful to avoid giving any impression that they are subject to the influence of corporate money.

“It is very difficult to quantify and find evidence for the big picture,” Stratmann, who was not involved in Ferguson’s study but has conducted similar research, told IBT. “There are so many things we do not observe, and cannot measure, that are important. Like pushing for a bill, or pushing against a bill, or spending time in a committee. All these negotiations that perhaps go on in conferences in between committees.”

“If you focus on the roll call votes, in some sense, you are focusing on a phenomena where you are most likely to see no effect because it is all so observable,” Stratmann told IBT.

But what has been observed is enough to convince many Americans that something must be done about money in politics. Several organizations, like T he Young Turks’ Wolf Pac and Represent.US, have called for an end to money in politics, and have published plans to go around Congress to institute reforms they don’t believe lawmakers are capable of enacting. Part of this effort is has included calling for a Constitutional amendment that would limit money in politics.

“Congress could easily pass reforms that would prevent the auctioning of our democracy, but they refuse to act,” Represent.US director Josh Silver said in a statement sent to IBT. “That’s why progressives and conservatives are going around politicians, and putting Anti-Corruption Acts on the ballot in cities and states – so voters can fix our nation’s corrupt political system themselves. "

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.