San Bernardino Attacker’s 28K Loan: Lack Of Regulation In Utah's Industrial Banks Allows For Risky Loans

In the months leading up to the lethal shootings he carried out with his wife in San Bernardino, California, Syed Farook applied for a loan of more than $28,000 from Prosper Marketplace, an online lender based in San Francisco. He received the money in his account more than two weeks before the attack, but filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) show he could have requested the loan as far back as October. Once he received the money, Farook withdrew $10,000 and transferred $15,000 to an account reportedly linked to his mother. It is believed he used the loan to fund the operation that left 14 dead and a score injured.

The ease with which Farook was able to get the loan has raised questions about the lack of regulation in the peer-to-peer lending market. There are two distinct risks for the individual lender and borrower in this model, but both result in a financial loss. The loan is made in a system that’s outside government regulation. Unlike government-backed loans, peer-to-peer loans are not insured by the Federal Reserve, but by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) which means a default can be costly for investors. Prosper faced serious legal issues in 2008 when the SEC issued a cease-and-desist order against the company, claiming it was selling unregistered securities. The other risk is around the verification of borrower’s financial information — the company takes the borrower’s information at face value without checking the accuracy of the information.

Two loans that stand out as possible matches for Farook in the last two months: One loan was given to an individual in California for $28,000, listed by the SEC on Nov. 2, and one for $28,5000 listed by the SEC Oct. 13 (the loan notes do not include the names of the borrowers). Both loan notes include salary ranges that match Farook’s as a health inspector and correctly identify the individual as not owning a home. The $28,000 loan shows the borrower as having no prior delinquencies, whereas the $28,500 loan reveals 27 delinquencies in the last 7 years. One of the loans is almost certainly Farook’s.

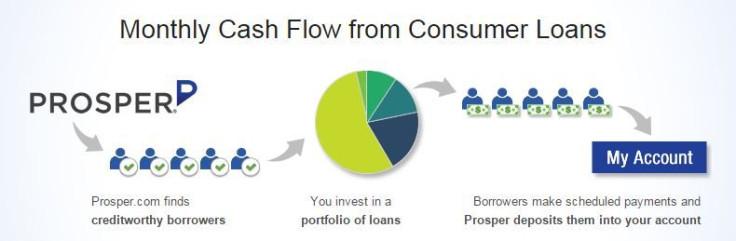

What is certain is that Farook took a loan out from Prosper: The investors set criteria on how their money is used, and Prosper distributes the money based on an algorithm to borrowers that match the lenders’ criteria. Once the process is complete, borrowers make fixed monthly payments and investors receive a portion of those payments.

Peer-to-peer lenders are not banks so they are not subject to the same federal regulations. Using a third party to create the loans enables lending companies to avoid regulatory costs, but individuals face risks with the platform because it is not governed by a complex regulatory structure.

A report issued by the Government Accountability Office in 2011 said borrowers often default on loans with no recourse for the lender. Furthermore, the report said, intermediary companies have not established an applicant screening system: LendingClub and Prosper do not verify information that borrowers supply, such as income, debt-to-income ratio, employment and homeownership status.

In a written statement to International Business Times, Prosper denied the report’s claims: “All loans originated through the Prosper platform are subject to identity verification and screening procedures required by law, including U.S. anti-terrorism and anti-money laundering laws. As part of our standard procedures, we also confirm that all loan funds are disbursed into a verified U.S. bank account in the borrower’s name.”

But underneath the loan notes filed on the SEC, Prosper states in the fine print: “Credit and homeownership information was obtained from borrower’s credit report and displayed without having been verified. Employment and income was provided by borrower and displayed without having been verified.”

The Rise of Peer-to-Peer Lending Companies

Prosper is representative of a surge in new companies that don’t make direct loans, but act as intermediaries, matching up borrowers with investors who want to lend. The loans from Prosper — and many other lending companies — have their roots in WebBank, an industrial bank based in Salt Lake City. Such banks are owned by corporate enterprises or individuals and aren’t regulated by the government. Farook’s deposit was only possible because Utah legislators have aggressively pursued a policy of banking deregulation.

Since 2009, the western state has been at the epicenter of industrial banking, employing thousands of people who have driven soaring profits through peer-to-peer lending schemes. In 2014, WebBank return on equity was about 44 percent, about five times the current average for U.S. banks. The Utah bank is one of the most profitable banks in the country, issuing loans to peer-to-peer lenders such as Prosper Marketplace and LendingClub. Two days after a loan is transferred to an account, WebBank collects interest on the money accrued during that window and earns a fee from the lender. In 2014, Prosper Marketplace used WebBank to make $1.6 billion worth of loans. The platform offers lenders the potential to earn higher returns than traditional savings vehicles and may offer borrowers broader access to credit.

This policy of nonstate interference has been immensely profitable for Utah’s industrial banking sector and the new lending institutions, which earn money on every loan deposited in a borrower’s account. This system also makes it almost impossible for the government to track the source of individual transactions. When news of Farook’s loan went public, there was wide speculation the money had been transferred by a terrorist organization such as the Islamic State group, also known as ISIS, or al Qaeda. This theory was given further credence when it was revealed that Tashfeen Malik, Farook’s wife, had pledged allegiance to ISIS in the hours before the attack. The FBI is investigating, but the challenge is tracking the payment through a lending system -- and a bank -- that is not regulated by the Federal Reserve.

This is not the first time Utah’s industrial banks, including WebBank, which funds Prosper’s loans, have drawn the ire of Washington. In 2009, a year after the global financial crisis, President Obama argued the parent companies of those banks pose a threat to the economy because they are exempt from routine scrutiny by the Federal Reserve. At one point in 2009, former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner presented a proposal to require industrial banks to submit to Federal Reserve oversight.

More recently, Treasury has pushed to investigate the online marketplace lending industry: In July, Treasury requested information about how marketplace lenders manage the risk of fraud and hacker attacks and how they protect consumers against scams or default but that study has yet to be released.

Meanwhile, industrial banks in Utah are taking full advantage of the lack of regulation in the peer-to-peer lending market while they still can, aiding potential terrorists along the way.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.