Scientists Freeze Great Barrier Reef Coral In World-first Trial

Scientists working on Australia's Great Barrier Reef have successfully trialled a new method for freezing and storing coral larvae they say could eventually help rewild reefs threatened by climate change.

Scientists are scrambling to protect coral reefs as rising ocean temperatures destabilise delicate ecosystems. The Great Barrier Reef has suffered four bleaching events in the last seven years including the first ever bleach during a La Nina phenomenon, which typically brings cooler temperatures.

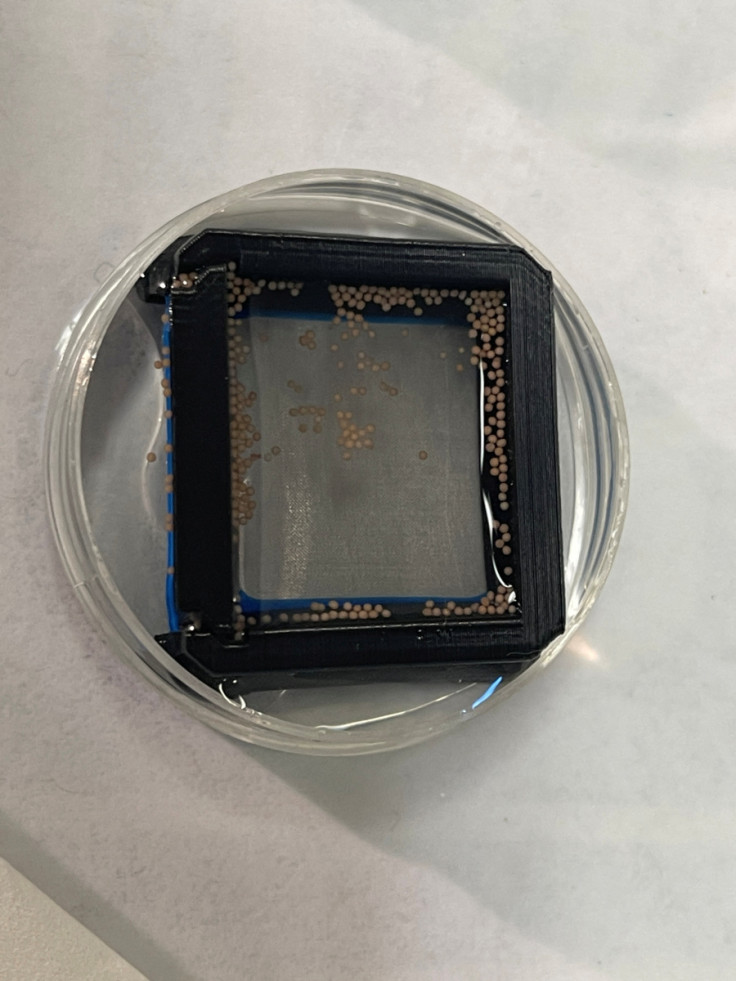

Cryogenically frozen coral can be stored and later reintroduced to the wild but the current process requires sophisticated equipment including lasers. Scientists say a new lightweight "cryomesh" can be manufactured cheaply and better preserves coral.

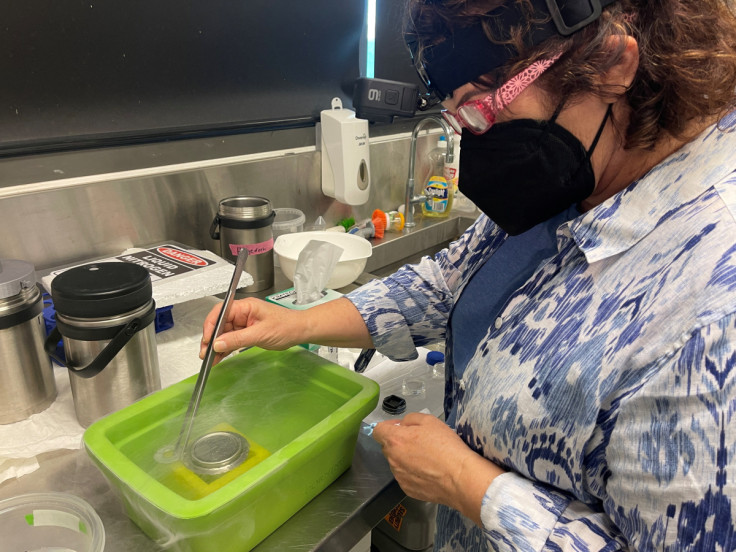

In a December lab trial, the world's first with Great Barrier Reef coral, scientists used the cryomesh to freeze coral larvae at the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences (AIMS). The coral had been collected from the reef for the trial, which coincided with the brief annual spawning window.

"If we can secure the biodiversity of coral ... then we'll have tools for the future to really help restore the reefs and this technology for coral reefs in the future is a real game-changer," said Mary Hagedorn, Senior Research Scientist at AIMS.

The cryomesh was previously trialled on smaller and larger varities of Hawaiian corals. A trial on the larger variety failed.

Trials are continuing with larger varieties of Great Barrier Reef coral.

The trials involved scientists from AIMS, the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, the Great Barrier Reef foundation and the Taronga Conservation Society Australia as part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program.

The mesh technology, which will help store coral larvae at -196C (-320.8?F), was devised by a team from the University of Minnesota's College of Science and Engineering, including Dr Zongqi Guo, a postdoctoral associate, and Professor John C. Bischov. It was first tested on corals by PHD student Nikolas Zuchowicz.

"This new technology that we've got will allow us to do that at a scale that can actually help to support some of the aquaculture and restoration interventions," said Jonathan Daly of the Taronga Conservation Society Australia.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.