Scientists Say Millions Of Black Holes Exist In Our Galaxy

The Milky Way galaxy is a minefield of black holes, with perhaps 100 million of the dangerous voids hiding among the stars, according to a new paper.

Researchers have estimated the number of black holes created by elderly stars for a study in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and the team says there are way more in our neighborhood of the universe than they were expecting going into the analysis.

Read: NASA’s Black Hole Images Really Suck

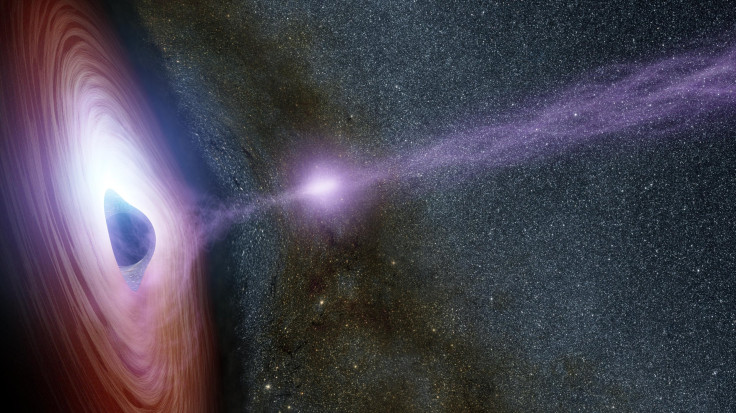

Massive stars that get really old might die in a dramatic fashion, collapsing in on themselves. When that happens, all of the mass that was once taking up a lot of real estate in outer space is suddenly pinched into a relatively tiny area, making for an object so dense that not even light, traveling faster than anything else in the universe, can escape its grasp — hence why black holes are dark.

The researchers wanted an idea of the number of these stellar-remnant black holes. To get their estimates, they used existing information about the distribution of stars: where they exist and how big they are. The estimates also told them how big they could expect black holes would be after the massive stars collapsed.

“We have a pretty good understanding of the overall population of stars in the universe and their mass distribution as they’re born, so we can tell how many black holes should have formed with 100 solar masses versus 10 solar masses,” study co-author James Bullock said in a statement from the University of California, Irvine. “We were able to work out how many big black holes should exist, and it ended up being in the millions — many more than I anticipated.”

There could be as many as 100 million in the Milky Way alone.

“Based on what we know about star formation in galaxies of different types, we can infer when and how many black holes formed in each galaxy,” researcher Oliver Elbert said in the statement. “Big galaxies are home to older stars, and they host older black holes too.”

According to the university, the research came about after scientists detected gravitational waves for the first time.

Gravitational waves are disturbances in space-time that come from enormous events, like two black holes crashing into and merging with one another — the circumstances under which scientists detected them almost two years ago. Those two colliding black holes were each about 30 times bigger than the sun, larger than some expected to see in a stellar-remnant black hole.

“That was simply astounding and had us asking, ‘How common are black holes of this size, and how often do they merge?’” Bullock said.

Read: Scientists Watch a Black Hole Collide With a Neutron Star

When it comes to black hole population and size, it depends on how big the home galaxy is; bigger galaxies make for smaller stellar-remnant black holes. The university explained that in larger galaxies, stars tend to contain a lot of metal, and they “shed a lot of that mass over their lives” so there isn’t much left over by the time they collapse. In smaller galaxies there aren’t as many heavy elements in the stars, so there is more mass remaining at the end of the big stars’ lives — paving the way for a big black hole.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.