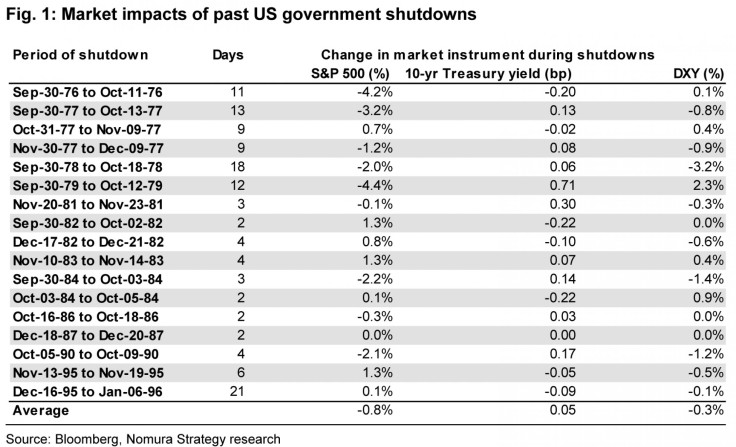

US Government Shutdown 2013: Past S&P 500 Performances Of Last 17 Shutdowns

The U.S. government began a partial shutdown on Tuesday for the first time in 17 years after Congress blew past a midnight deadline to pass a crucial spending bill. Economists say the shutdown could last for several weeks, but the impact on the stock market is going to be relatively small.

This is not the first time that the government has turned its lights off. In fact, during the last federal government shutdowns (two episodes between November 1995 and January 1996, to be exact), the S&P 500 (INDEXSP: .INX) actually rose slightly, according to Nomura. And of the 17 individual “instances” (usually lasting less than two weeks and often less than one), equities rallied in eight, with the average S&P 500 performance being negative but not even by 1 percent:

“The shutdown will likely add to the budget deficit,” Ethan Harris, a top economist with Bank of America, said in a note. “It is costly to stop and start programs.”

The 1995-96 shutdown directly added $1.4 billion to the deficit (about $2.5 billion in today’s dollars). Moreover, the shock to growth will undercut tax revenues.

Michael Kurtz, chief Asian equity strategist at Nomura, said: “A U.S. debt default on the other hand, even if ‘technical,’ could be more catastrophically destabilizing, given that the U.S. dollar’s status as the world's primary reserve currency has already suffered second-guessing from some quarters (at least) in recent years, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield is almost universally regarded as the global ‘risk-free’ benchmark interest rate and given that the U.S.’s fragile fiscal position depends on borrowing costs that in turn require the maintenance of international faith and credit.”

According to Nomura, the probability of a U.S. default is low. “In some sense it’s like the use of nuclear weapons. The consequences of such a course of action would be so negative as to render it extremely unlikely that policymakers would let events precipitate such an outcome,” Kurtz said.

The threat still leaves markets, however, with the particularly tricky task of discounting a very low-probability scenario that carries a very large (and adverse) potential impact.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.