U.S. Jobless Benefits Rolls Grow; Key Factory Output Gauge Slumps

The number of Americans enrolling for unemployment benefits rose for a third straight week last week to the highest in eight months and a closely watched gauge of factory activity slumped this month, the newest indications the U.S. economy is slowing under the weight of rising interest rates and high inflation.

The latest data are likely to further fan fears of a recession that were already on the rise with the Federal Reserve lifting interest rates at the most rapid pace in decades to blunt inflation running at the highest levels since the 1980s. A Reuters poll released on Thursday showed economists assign a median probability of recession in the next 12 months at 40%, up from 25% in the previous month's survey.

In the week ended July 16, initial claims for state unemployment benefits rose 7,000 to a seasonally adjusted 251,000, the highest since last November, from an unrevised 244,000 a week earlier, the Labor Department said on Thursday. Economists polled by Reuters had forecast 240,000 applications for the latest week.

Since bottoming out at a near-record low in March, the level of new claims has been grinding upward and is now 85,000 higher than that low point. Meanwhile, the number of people receiving benefits after an initial week of aid rose by 51,000 - the largest increase since November - to 1.384 million during the week ending July 9, the claims report showed. That was the highest number since April.

(GRAPHIC: Jobless claims -

)

The weekly claims report is viewed as among the most timely indicators of the health of the job market and has been closely watched for signs that a clutch of high-profile corporate layoff announcements might be a harbinger of a larger wave of job cuts. Even with the recent pickup in new claims and in the ranks of ongoing benefits recipients, both remain relatively low by historic measures.

Continuing claims, for instance, had averaged about 1.7 million in the year before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the current level, at more than 300,000 below that figure, indicates those who lose their jobs are getting new ones in short order, Jefferies economists Thomas Simons and Aneta Markowska said in a client note.

"Several large companies have indicated that they intend to lay off various numbers of workers, but the claims data does not suggest that much of this layoff activity has begun in any meaningful way," they said. "If it has, then the negative impact is overwhelmed by continued strong demand for labor by other firms."

Despite some loss of momentum, hiring has remained robust, with 372,000 jobs created in June and a broader measure of unemployment falling to a record low. Demand for labor remains fairly strong, as well. There were 11.3 million job openings at the end of May, with nearly two job openings for every unemployed person.

FACTORY SLUMP

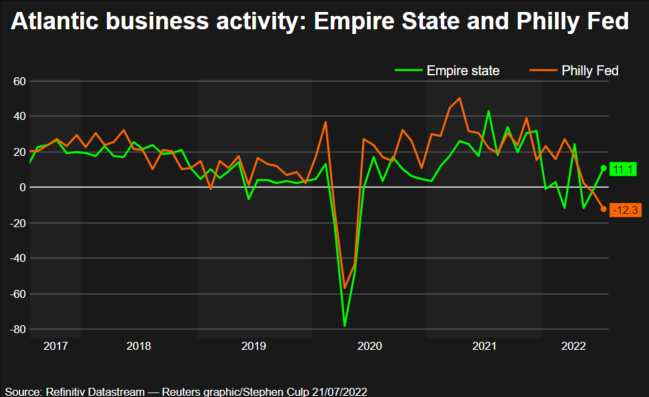

Meanwhile, a measure of manufacturing activity in the Mid-Atlantic region slumped in July to the lowest since May 2020 and firms reported the darkest outlook in more than four decades.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia's monthly manufacturing index slid this month to a reading of minus 12.3, the second consecutive monthly contraction, from minus 3.3 in June. Economists polled by Reuters had a median expectation for a reading of zero.

Respondents to the regional survey - seen by economists as a reliable signal for the benchmark national reports that follow it - indicated they see a sharp slowdown in activity in the months ahead. The six-month outlook index slid to negative 18.6 - the lowest since December 1979 - from negative 6.8 in June.

Still, the report had some silver linings, for the Fed in particular: Hiring continued to grow modestly and the survey's inflation measurement eased, with firms reporting their input costs fell for a third straight month to the lowest since January 2021.

(GRAPHIC: Philly Fed -

)

The Fed is closely watching the incoming data for signals that inflation is finally starting to come down, but it has pledged not to let up on its monetary policy tightening until inflation moves materially lower toward the U.S. central bank's 2% annual target. The Fed's preferred inflation measure was last reported at 6.3% in May and likely moved higher in June, a figure that will not be reported until after policymakers meet next week.

Another key inflation gauge - the Consumer Price Index - rose to 9.1% in June, the highest rate since 1981, which had stoked market bets that the Fed might raise interest rates by as much as 1 percentage point at the July 26-27 policy meeting.

A number of Fed officials pushed back against that speculation, and following Thursday's data, market expectations firmed around a 0.75-percentage-point increase. That would match June's increase, which was the largest since 1994.

Since March, the Fed has hiked its benchmark overnight interest rate three times from the near-zero level to a range of 1.50% to 1.75%, and the CME Group's FedWatch tool indicates it could rise by another 2 percentage points by end of 2022 to a range of 3.50% to 3.75%.

The Fed would like to cool demand and economic activity without triggering a surge in unemployment, a so-called "soft landing" scenario. Officials have conceded, though, that their path to that outcome is increasingly challenging.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.