Venezuela Pushing For OPEC Oil Production Deal As Slumping Prices Erode Government Revenue

Venezuela, the country suffering the most from low oil prices, is making an increasingly desperate pitch to freeze the world’s oil output and shore up prices. The nation’s oil minister was in the Middle East this week to help facilitate what could become the first global oil deal in 15 years.

Venezuela is uniquely suited to bridge the discussions because it poses little threat to other oil producers, analysts said.

The country’s crude output is already plunging due to underinvestment in the energy sector, and foreign oil companies have little interest in spending more dollars to extract Venezuela’s high-cost crude. Venezuela is less a competitor than a mediator for major oil-producing nations such as Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran, said Francisco Monaldi, a fellow in Latin American Energy Policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston.

“Everyone knows that Venezuela is not going to increase production,” he said. “The only thing that Venezuela actually provides is a way of communicating between countries that have very bad relationships.”

Venezuela joined Saudi Arabia, Qatar and non-OPEC producer Russia in an agreement Tuesday to freeze oil output at January levels, which hit near-record highs. But the preliminary deal, forged in Doha, is conditional on other nations agreeing to participate. Eulogio Del Pino, Venezuela’s oil minister, said the group of producers planned to monitor output and prices for four months.

Del Pino was in Tehran Wednesday trying to persuade his Iranian and Iraqi counterparts to cooperate. After the two-hour meeting, Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh remained silent on his country’s plans for production, which is expected to accelerate this year with the lifting of Western sanctions. Zanganeh said he supported efforts to calm oil markets, including Tuesday’s pact, but called the agreement a “first step, and more steps must follow,” according to Iran’s state-run oil news service Shana.

Venezuela has played a key role in earlier oil sector negotiations.

In 1998, it negotiated a deal together with Saudi Arabia and non-OPEC member Mexico to cut global oil production and reverse a slump in oil prices, which at the time touched a nine-year low. Venezuela at the time was in a stronger position economically and investing heavily in new oil production -- two trends that quickly reversed when the late President Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999. At a meeting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia's capital, OPEC's 11 members agreed to cut production by 1.23 million barrels per day, with non-OPEC nations -- including Russia, Oman and Mexico -- pledging cuts of 270,000 barrels per day.

Venezuela was also central in the founding of the OPEC oil cartel in 1960, which initially included five members: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the South American nation. As an outsider in Middle East politics, Venezuela has found it easier to serve as a broker between feuding countries, including Saudi Arabia and Iran or Saudi Arabia and Russia.

"They feel that they can play a diplomatic role in that sense," Monaldi said.

During the current oil-price slump, Venezuela has repeatedly pressed for an emergency OPEC meeting as slumping oil prices erode government revenue.

Crude prices have plunged around 70 percent from their mid-2014 peak to around $30 a barrel, spurred by the widening imbalance in oil supply and demand. Producers are now supplying between roughly 1.5 million and 2 million barrels a day more petroleum than the world is consuming, pushing global oil stockpiles to record levels. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and other analysts project the oversupply could potentially push prices below $20 a barrel before the rout is over.

The price plunge has slammed nearly every oil-dependent economy. Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, posted a budget deficit of $98 billion -- or 15 percent of its gross domestic product -- last year amid plummeting oil export revenues, which account for about 80 percent of its total budget revenue. In Russia, where oil and natural gas revenues supply about half of Russia’s federal budget, the economy could shrink by 0.8 percent in 2016 if oil prices average $40 per barrel this year, Russia’s Economy Minister projected in January.

Yet no country is suffering more than Venezuela, the twelfth largest oil producer in the world. The South American nation relies on crude sales for roughly 96 percent of its exports, and more than half the country’s GDP. Venezuelan economists estimate that for every dollar off the price of oil, the government loses as much as $700 million in estimated revenue a year.

The oil-price collapse is exacerbating years of economic mismanagement by Caracas. Already behind on billions of dollars in debt it owes for imports, Venezuela is quickly running out of cash, basic consumer goods and vital health care services. The International Monetary Fund said it expects Venezuela’s consumer inflation to rocket this year to 720 percent.

“Venezuela might default by the end of the year, including the national oil company [PVDSA], which would be a very messy affair if it happens,” Monaldi said.

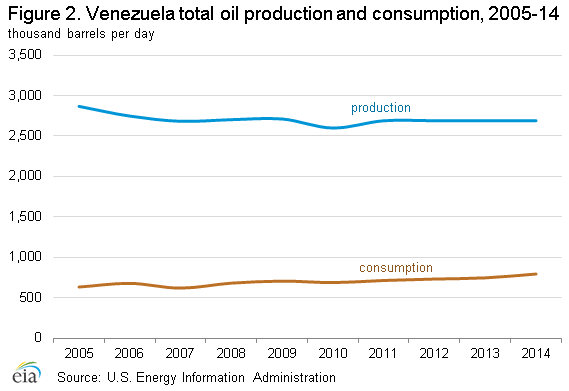

Venezuela’s economic woes also mean the country is unlikely to invest in its beleaguered state-owned oil sector and accelerate crude production. The country holds the world’s largest proven crude reserves, yet output has steadily fallen each year since the late 1990s. Its lower-cost, easier-to-reach wells are running dry, and the country hasn’t invested enough to ramp up production of unconventional sources, including heavy oil sands crude. Its foreign partners, including U.S. energy giant Chevron Corp. and Italy’s Eni, are less willing to invest in heavier, higher-cost crude at today’s oil prices.

“The situation for Venezuela is very dire,” Monaldi added. “They don’t see any way out other than getting these other producers to signal that they will not continue with the increase in production.”

Still, analysts this week said they were skeptical that such a signal could result in meaningful changes in the global oil markets. They framed the Venezuela-led talks as primarily a public relations campaign by oil producers to show they’re willing to cooperate, even if they don’t actually take steps to soothe the supply-demand imbalance.

Kevin Book, who heads the research team at ClearView Energy Partners in Washington, pointed to the fact that Saudi Arabia’s pledge to freeze oil output is entirely contingent on other producers following suite. “A promise to freeze production, as long as everybody else stops producing, isn’t worth the paper it’s written on,” he said.

And even if oil producers did reach an agreement to cap or curb production, they might not trust one another to actually comply or accurately report their data, particularly with Russia. “There’s no such thing as R-OPEC,” Book said, referring to the oil cartel. “There’s a big trust gap. Whatever they say, the challenge of actually doing it is still greater than the agreement itself.”

Colin Fenton, an energy researcher in Boston, said freezing oil production wouldn’t actually help resolve another potential challenge facing oil markets: declining demand.

U.S. GDP, for instance, braked sharply in the fourth quarter of 2015, rising at a 0.7 annual rate, as low oil prices undermined investments by energy firms and unseasonably mild weather cut into consumer spending, the Commerce Department reported. Japan’s economy shrank 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter on a sharp decline in consumption. Eurozone countries saw GDP rise 0.3 percent in the same period, while China posted its weakest fourth-quarter growth since 2009, at 6.8 percent.

“Even if production is frozen, it’s still much higher than demand at the present moment, and demand is beginning to falter,” said Fenton, a fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

“Venezuela has the ability to create a headline. It has the ability to create motion, to actually create a meeting in the Middle East,” he added. “But these are very crystal-eyed markets. They ask the tougher question of what is supply and demand.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.