Wealth Inequality Is Approaching Its Roaring ’20s Peak

Plenty of research shows that income inequality in the U.S. has risen dramatically since the 1970s. What’s even more startling is rising wealth inequality, the difference among classes of the assets people own through homes, pensions, bank accounts and stock portfolios. Only a tiny portion of Americans have seen their wealth increase over the past 30 years.

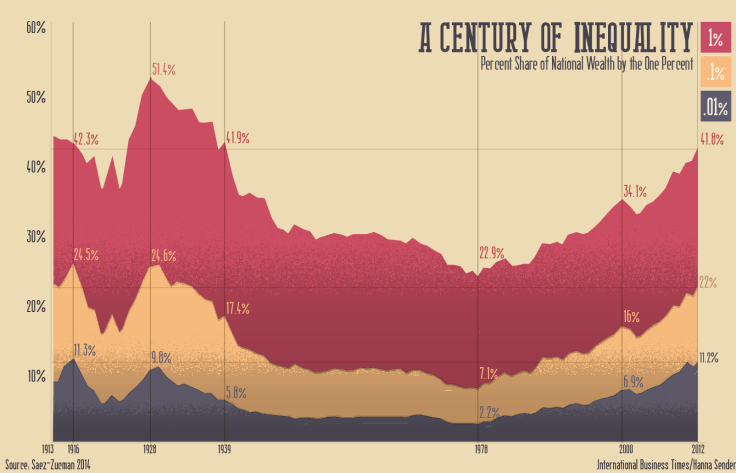

Using data on capital income reported on individual tax returns since 1913, economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman say in a recent working paper that the top 1 percent increased their wealth more than tenfold from the late ’70s to 2012, while most Americans haven’t increased their wealth at all. In 2012, the top 1 percent (1.6 million families with net assets above $20 million) owned 42 percent of wealth, while the top 0.1 percent (160,700 families with net assets above $20 million) owned 22 percent of wealth.

The 22 percent share held by the richest 0.1 percent is now nearly as high as the 25 percent held by the group in the late 1920s, a time of Gatsby-like inherited fortunes. Economists disagree over whether the rise in income inequality is harming Americans’ ability to climb into higher income classes, but regardless, most Americans are not seeing much benefit from economic recovery.

Saez, a French and American economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, developed the heavily cited top 1 percent estimates. He has also tracked incomes of the rich and poor around the world with French economist Thomas Piketty, who warns in his best-seller Capital in the Twenty-First Century that a rise in inherited wealth could erode the democratization of wealth Americans achieved in the postwar decades. Zucman is an assistant professor at the London School of Economics.

Over the past century, wealth inequality has followed a “U” pattern, Saez-Zucman found. From the Great Depression in 1929 through the 1970s, the share of wealth owned by the richest families fell steadily. Home ownership rates skyrocketed, and workers began accumulating retirement savings through newly developing pension programs. From about 1940 to 1970, wages rose at about the same level for all Americans, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The share of wealth held by the bottom 90 percent of Americans gradually increased from 15 percent in the 1920s to a peak of 36 percent in the 1980s, according to Saez-Zucman.

In the 1970s, as more women and foreign workers entered the job market, employment began rising faster, but wages began stagnating. More poor and middle-class Americans began racking up debt with higher mortgages, student loans and consumer credit than ever before. The debt eroded their wealth, but was masked with rising home values, the primary assets of middle-class families. Those families lost the majority of their assets when home values tumbled in the late 2000s. By 2012, the bottom 90 percent owned only 23 percent of the country’s wealth, about as much as in 1940, Saez-Zucman say.

Since the most recent recession in 2008-2009, most Americans haven’t recovered the wealth they lost, while the top 1 percent, with assets primarily on Wall Street rather than in the housing market, nearly reached their peak wealth of 2007 in 2012.

Wages for the top 1 percent have accelerated over the past few decades (think company executives), with the wealthiest earning a greater share of their income from labor rather than inheritances and capital (think more Mark Zuckerbergs, fewer Paris Hiltons). More of the wealthiest are also younger than in the 1960s and tend to invest large portions of their wages into more capital, further increasing their wealth. While the top 1 percent sock away an average 35 percent of their income, the bottom 90 percent of families save little to zero.

Saez and Zucman recommend a combination of policies to help people save, boost their wages, eliminate preferential tax rates on capital income compared with wage income and institute a progressive estate tax. They also want the Treasury Department to collect more information on bank account and 401(k) balances so that economists can better track Americans’ wealth.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.