What Old Dinosaur Bones Reveal: 3D Technology Reveals Fossil Secrets

Technology has uncovered new information about an old dinosaur, including teeth that were hidden inside its jaw bone.

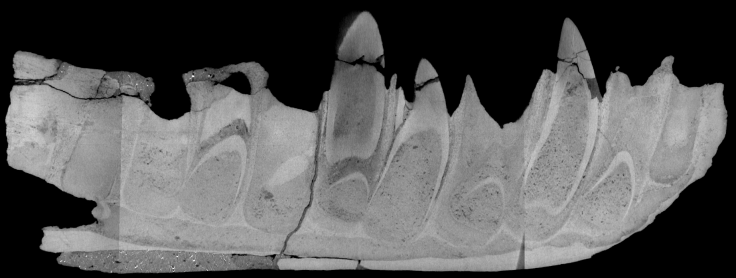

Scientists used CT scanning equipment and software that had yet to be invented when a megalosaurus fossil was discovered about 200 years ago, creating a 3D, layered image of the bones. The imaging technology allowed the researchers to look inside them, bringing to light the hidden teeth as well as marks from previous restoration work done on the specimen, according to a study presented at the International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference, held in Italy last month.

The carnivorous megalosaurus lived about 167 million years ago and the one involved in this study was the first dinosaur to be named and described scientifically. That happened in 1822 with the first fossil of its kind, known as Megalosaurus bucklandii. Over time scientists have learned more about the extinct creature, whose name translates to “great lizard,” finding that it walked on two legs instead of four — its front arms being short — and that it had long, sharp teeth. It would have been about 30 feet long and weighed about 3,000 pounds.

Read: The T. Rex Was Covered in Scales, Not Feathers

Scans of the Megalosaurus bucklandii , which is at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, found five teeth “that were growing deep within the jaw before the animal died — including the remains of old, worn teeth and also tiny newly growing teeth,” the University of Warwick said in a statement.

Another important find of the CT scans was a history of the conservation work that had been done on the fossil. The study found historical records of that type of work are sometimes incomplete, but they are crucial in informing scientists about how to proceed in restoring or maintaining something fragile.

“The far-reaching implication of this is an inability to assess the true condition of restored specimens” without potentially doing damage to them, the study said. “Far more threatening is the risk of elaborate forgeries and artificial grafts on incomplete genuine specimens that can, on occasion, even fool the most elite of subject experts.”

CT scans, however, are a noninvasive way of analyzing fossils and their internal structure.

The scans are important to research because they let the experts “nondestructively investigate the subsurface details of an artifact to provide essential information on [the] condition of a specimen,” the study explained. It does not threaten “the integrity of the original specimen.”

Scientists use them in other fields as well, for example, those who want to investigate the layers of an Egyptian mummy without destroying it. In that case, a CT scan shows the researchers what’s inside a sarcophagus, below the many wrappings of a mummy and into what is left of the corpse.

For the historic megalosaurus, there were no records of its restorations despite it having undergone a lot of work, including “many parts of the specimen being replaced with what is assumed is plaster” to fight off both “natural and presumably accidental degradation.”

Read: Sorry, But Jurassic Park Is Not Possible In Real Life

Some of the damage it sustained might have happened “when it was removed from the rock, possibly shortly after it was discovered,” the university said.

The CT scans found two kinds of plaster as well as other clues about the work previously performed.

“When I was growing up I was fascinated with dinosaurs and clearly remember seeing pictures of the megalosaurus jaw in books that I read,” researcher Mark Williams said in the Warwick statement. “Having access to and scanning the real thing was an incredible experience.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.