Winning Aleppo Would Be Major For Syrian Regime But Devastating For Those Stuck Inside

BEIRUT— Each faction fighting in Syria has distinct views on religion and governance, as well as disparate foreign allegiances. Their wildly opposing objectives have made it as yet impossible to reach a diplomatic solution at this year’s abortive peace talks in Geneva, but the same cannot be said for Syria’s battlefield. One aim that is shared by the majority of factions is the ardent vying for control of Aleppo, Syria’s biggest city.

Before the war, Aleppo, located in Syria’s northwest near the Turkish border, was the country's largest commercial hub. Five years on, its strategic location and symbolic significance make the province and its capital one of the country's most coveted territories. The city was once famous for its handmade-soap and bread factories, but in recent years it has become better known as the site of bitter fighting between Syrian President Bashar Assad and his pro-regime forces, and opposition groups. Since 2012, there have been four major battles in Aleppo between rival combatants, but the regime has never succeeded in gaining as much ground as it has in the past week.

For hundreds of thousands of Syrians, the unimaginable is about to happen: The war is about to get worse as Aleppo residents confront the possibility of a brutal siege after the Syrian government and its Russian allies cut the last secure supply line into opposition-held neighborhoods. Last Monday, pro-regime forces, backed by Russian airstrikes, seized the towns Nubl and Zahraa in northern Aleppo province.

From this point, only five miles of supply lines are estimated to remain. If, as is likely, they are surrendered to the regime, Assad's forces will not only have access to the rest of the country but also the power to isolate some 350,000 people left in opposition-held areas of the city.

Losing Aleppo would be a major blow to the rebels' strength and morale, and would tip the scales in the president's favor at the negotiating table.

"Aleppo is the cosmopolitan New York City of Syria. Whoever is in control … has a base of operations into the countryside that is easily defendable and full of resources for industry, trade and weapons,” said Chris Kozac, a Syria analyst at the Institute for the Study of War. “Things are going to get worse before they get better. That’s the sad but accurate truth.”

Mercy Corps delivers aid to up to 500,000 in #Syria each month. Now, “We are cut off from Aleppo City." Read: https://t.co/EeIZGn8C11

— Mercy Corps (@mercycorps) February 7, 2016

Humanitarian organizations have expressed their concern that a siege is imminent. “Our staff on the ground are saying it’s the most intensive bombing they have seen ever since the start of the war,” said Christine Nyirjesy Bragale, director of media relations at Mercy Corps, a U.S.- and U.K-funded international development company and the largest aid agency operating in northern Aleppo aside from the United Nations.

The organization began stockpiling supplies before the regime’s offensive began. Families with access to fuel received a food basket with essentials such as lentils, bulgur wheat, rice, tuna, salt and chickpeas. Those who cannot cook were supplied with a food basket with ready-to-eat meals. Mercy Corps also provided winter supplies and hygiene kits to families in northern Aleppo, but now it fears that vital supplies will run out without access to the main supply route in the north.

“It feels like the beginning of the siege, and we are very concerned,” Bragale told International Business Times. The organization has limited access to other routes, but this is risky because of bombings and various checkpoints en route, each controlled by a different faction.

"Food has become the No. 1 priority,” Bragale said. “Families are saying we’re their only source of food.”

But besieging Aleppo isn’t enough to win the war. The city is a microcosm of the conflict itself with all its attendant complexities.

Assad’s army and allied forces first attempted to encircle Aleppo in February 2015. After that attempt failed, regime forces spent eight months preparing for the recent push. Russia and Syria began with increased attacks around Aleppo and Idlib so opposition forces would have to split their resources defending both provinces. By mid-October, pro-regime ground forces began their push on Aleppo’s southern front, previously controlled by various Syrian rebel groups, including Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zenki — one of the first rebel groups to be part of the U.S. train-and-equip program — and the First Regiment of the Free Syrian Army.

Russian airstrikes have been near-constant since the country began its first aerial bombardment of Syrian territory four months ago. On the ground, fighters from Lebanese Shiite armed group Hezbollah and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard are leading thousands of fighters against the rebels. Syrian fighters are among the pro-regime ground forces, but the majority are from Iran-backed Iraqi Shiite militias. Combined, these forces are working to devastating effect.

Omar Khatab, a rebel fighter in southern Aleppo, had to help his family flee even before the newest operation began, because of a regime ground incursion into the south. Now his family is waiting to cross over into Turkey along with tens of thousands of other Syrians who are fleeing the bombs.

“Soldiers from Iraq and Iran came to our village. My family [is now] in the camp,” Khatab said. “The war is killing us. The whole world is killing us.”

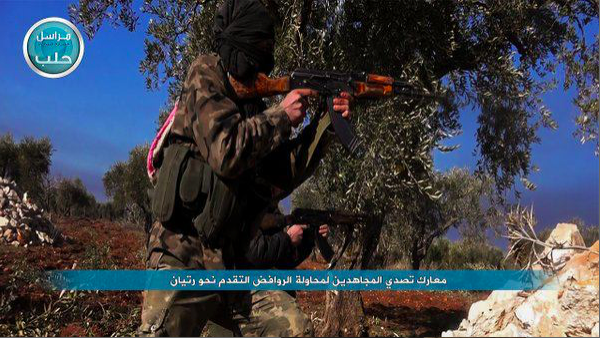

But the rebels haven't given up the fight. A multitude of anti-regime factions — including various rebel groups, terrorist organizations like al Qaeda’s Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State group — are fighting Assad's forces. Reports circulated over the weekend of a possible unification of opposition groups in Aleppo, including the Nusra Front. This fell through when Nusra refused to shed its ties to al Qaeda, “but the incentive is still there and is only going to get stronger,” Syria analyst Kozac said.

"This is a decisive battle for us," a fighter with the Levant Front, a coalition of rebel groups based in northern Aleppo, told Syria Deeply.

"Aleppo is the heart of the Syrian revolution and over our dead bodies will we let it fall to the hands of the regime.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.