Winter Storm Juno: Northeast Blizzard Is Latest In Rising Number Of Extreme Weather Events Taking Economic Toll

The massive blizzard bearing down on the U.S. Northeast is poised to be the latest in a rising number of extreme weather events that take a growing toll on the U.S. and global economies. The winter storm, dubbed Juno, is threatening to shut down roads, damage infrastructure, shutter offices and strand millions of people at home this week.

It could dump up to 3 feet of snow across seven states between Monday and Tuesday evening, the National Weather Service predicts. Power outages, public transit failures, and thousands of flight cancellations are likely in major cities along the Boston-to-Philadelphia corridor. “This could be a storm the likes of which we have never seen before,” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio warned at a Sunday news conference.

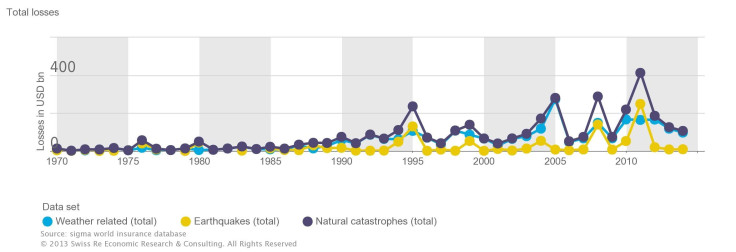

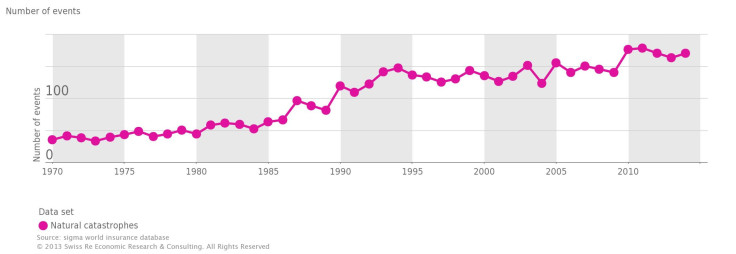

Across the world, natural and man-made disasters totaled $113 billion in 2014, according to preliminary estimates from Swiss Re, the world’s second-largest reinsurance company. While the number is lower than 2013 and 2012 totals, it still indicates the rising threat that people and properties face from extreme weather events.

“Our vulnerability to these hazards has increased tremendously,” Andrew Castaldi, head of Swiss Re’s Catastrophe Perils Americas division, says. The company estimates that insured losses from extreme storms accounted for 0.077 percent of global gross domestic product from 2004 to 2013, up from 0.0018 percent during the 1974-1983 period.

The chief reason for rising economic losses is that more people are moving to hazardous areas -- namely coastal cities -- and building properties and infrastructure squarely in harm’s way, Castaldi says. He notes that many factories today rely heavily on robotics and telecommunications networks to operate, making them more susceptible to shutdowns than in the days when manual labor ruled in manufacturing. More homes are filled with pricey electronics and have multiple vehicles compared to decades earlier, raising the risk of personal losses from water and wind damage.

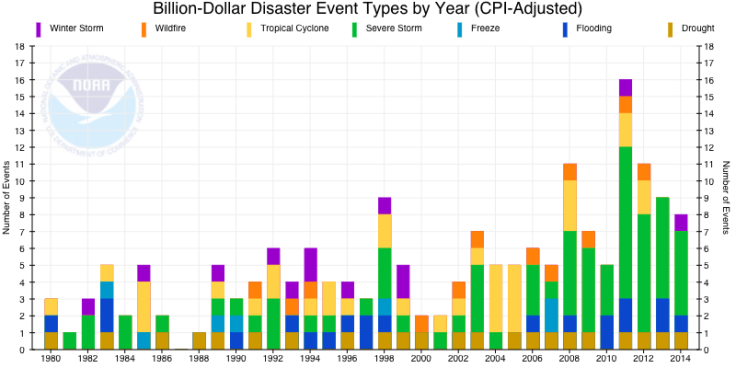

In the United States, such trends are causing a rise in $1 billion weather and climate disasters, including blizzards, tropical cyclones, flooding and drought. Nearly 180 extreme storms have slammed the country since 1980, racking up a total of more than $1 trillion in losses, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Climatic Data Center.

Winter storms alone accounted for 15 percent of U.S. catastrophe losses in 2014, the Insurance Information Institute found. That includes last winter’s brutal blizzard in early January, which crippled parts of the U.S. Northeast, Southeast and Midwest for four days. Enduring frigid temperatures and snowy weather throughout the season added further economic pain as worker productivity plummeted and consumers made fewer trips to grocery and retail stores. The U.S. GDP rose by just 0.1 percent in the first quarter of 2014, down from a 2.6 percent rise in the previous quarter, because of the “disruptive effect” of severe weather in January and February 2014, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“In recent years, severe storm events causing damage in excess of $1 billion have become more frequent, but there is also more to be damaged as population and wealth increase,” Adam Smith, an applied climatologist at the data center, says.

The $1 billion loss figure includes a mix of physical and intangible economic losses, such as damage to buildings, lost revenue due to business interruptions, destruction of crops and livestock and the inability of ships to access ports. But it doesn't include all the economic losses related to workers’ time and productivity “due to the inherent complexity and data limitations,” Smith says.

Climate change is also exacerbating the severity of storms in certain cases, though it is difficult for scientists to calculate precisely by how much. During 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, for instance, coastal flooding was more extensive and damaging because of sea level rise in the New York Harbor, according to the city’s panel of climate scientists. In the coming decades, rising global temperatures are expected to alter the frequency, intensity and duration of extreme events, which will further multiply the costs of climate catastrophes.

“There have been observed trends in some types of extreme events that are consistent with rising temperatures,” including heavy precipitation events, more intense droughts and heat waves, Smith says. “Research on climate change’s effects on other types of extreme events continues.”

Castaldi says he expected global economic losses will continue to climb, in part because people will keep moving to coastal cities, where rising sea levels are raising the changes of floods and storm surges. “Absent any climate change or hazard change, we expect insured losses to double every decade … with the gap between insured losses and total economic losses increasing,” he says.

The effects of extreme weather events can be contained if countries and cities prepare and adapt, experts say. A recent Swiss Re report cited case studies that found nearly 70 percent of climate change-generated losses can be avoided using adaptation measures, including building artificial reefs, installing “micro” electric grids and improving evacuation and emergency response efforts.

Smith pointed to New York City’s post-Sandy resiliency plan as “a positive example” of shoreline planning and investment. “Given that tropical cyclones create the most costly damage, on average, and that coastal areas continue to grow in population density and valuable infrastructure, coastal cities should think about how to incorporate damage mitigation plans into their future growth vision and further insure against flood risks,” he says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.