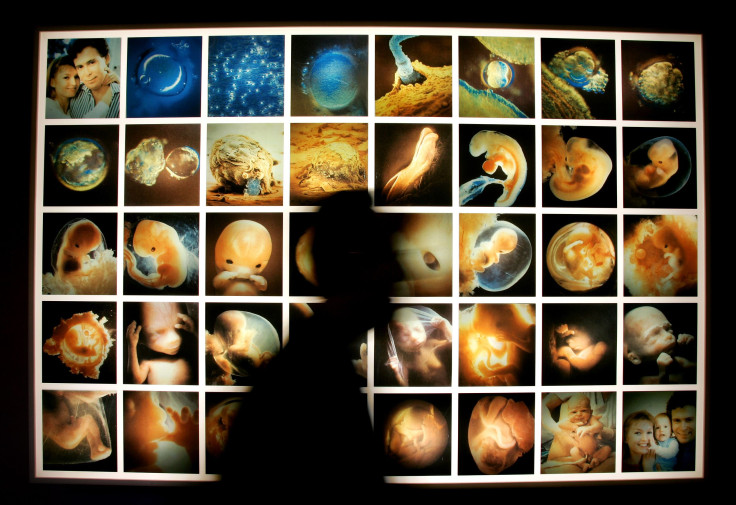

World's First Genetically Modified Human Embryo Created, Chinese Scientists Claim In New Study

The term “designer babies,” which refers to an offspring created through a genetically engineered embryo, has always had dystopian connotations, conjuring up images of children manufactured in “hatcheries” similar to those described in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Embroiled in ethical controversies, scientists have stayed away from actually attempting to genetically modify an embryo, although rapid progress in genetics has definitely brought this within the realm of possibility.

Now, a team of Chinese scientists have reported, in a paper published in the journal Protein and Cell, that they have conducted such experiments on embryos. Although the researchers, hailing from the Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, tried to stave off criticism by using "non-viable" embryos that cannot develop into a full-fledged fetus, the process, which uses a gene-editing technique known as CRISPR/Cas9, has already raised hackles in the scientific community.

“I believe this is the first report of CRISPR/Cas9 applied to human pre-implantation embryos and as such the study is a landmark, as well as a cautionary tale,” George Daley, a stem cell biologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, told Nature’s news division. “Their study should be a stern warning to any practitioner who thinks the technology is ready for testing to eradicate disease genes.”

The researchers tried to tweak the gene responsible for beta-thalassaemia -- a genetic blood disorder -- through the aforementioned technique. They injected 86 embryos and then waited 48 hours, during which the embryos grew to about eight cells each. Of the 71 embryos that survived, 54 were genetically tested. Of these, only a tiny fraction contained the replacement genetic material.

“If you want to do it in normal embryos, you need to be close to 100 percent. … That’s why we stopped. We still think it’s too immature,” Junjiu Huang, the lead researcher, reportedly said.

Editing human embryos is problematic because it could have long-term, unintended consequences. One such effect was visible in this particular study. A surprising number of “off-target” mutations that acted on other parts of the genome were detected. “If we did the whole genome sequence, we would get many more,” Huang reportedly said.

The process also raises the question of consent, which, in such cases, would be impossible to obtain since embryos obviously cannot consent to having their genes altered.

“It underlines what we said before -- we need to pause this research and make sure we have a broad based discussion about which direction we’re going here,” Edward Lanphier, president of California-based Sangamo BioSciences, which uses gene-editing techniques on adult human cells, told Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.