Drought In Amazon Could Lead To Accelerated Global Warming

A new study reveals a drought last year in the Amazon basin caused the forest to lose significant levels of vegetation, which in turn could accelerate the pace of global warming.

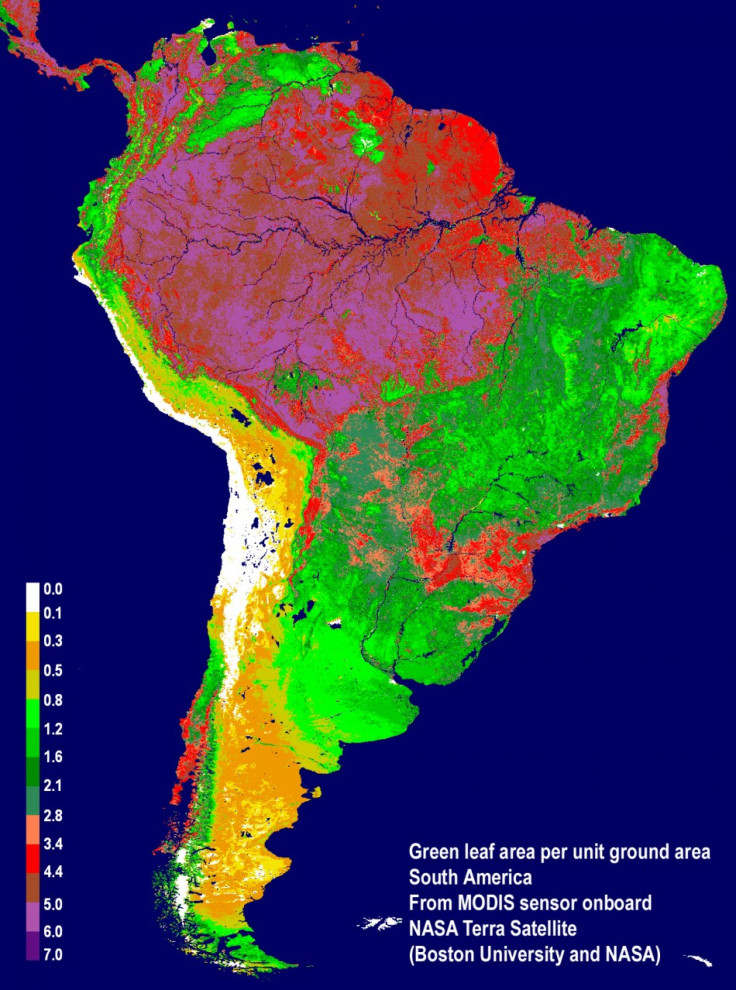

The study, conducted by an international team of scientists and funded by NASA, uses specific satellite imaging data provided by the agency to draw its conclusions. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellites provided more than a decade's worth of data for scientists who studied the de-vegetation of the Amazon rainforest.

The scientists say changing climates with warmer temperatures and altered rainfall could lead to the rainforests turning into grasslands or woody savannas. This causes carbon stored in the rotting wood to be released into the atmosphere, which would add to the greenhouse gases present.

The greenness levels of Amazonian vegetation -- a measure of its health -- decreased dramatically over an area more than three and one-half times the size of Texas and did not recover to normal levels, even after the drought ended in late October 2010, Liang Xu, the study's lead author from Boston University, said in a statement.

The MODIS vegetation greenness data suggest a more widespread, severe and long-lasting impact to Amazonian vegetation than what can be inferred based solely on rainfall data, said Arindam Samanta, a co-lead author from Atmospheric and Environmental Research Inc. in Lexington, Mass., in a statement.

The drought was one of the worst in Amazonian history. In rivers across the basin, water levels reached all time lows by the time the drought ended in October of last year. According to the researchers, in 109 years of Rio Negro water level data at the Manaus harbor, 2010 was the driest on record.

To gauge the impact the drought could have on the overall environment, the researchers used NASA's Earth Exchange (NEX) supercomputing facility. The study will be published by Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

Timely monitoring of our planet's vegetation with satellites is critical, and with NEX it can be done efficiently to deliver near-real time information, as this study demonstrates, study coauthor Ramakrishna Nemani, a research scientist at Ames, said in a statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.