Human-Induced Climate Change Triggered The Middle East’s Worst Drought In 900 Years, NASA Says

Over the past four years, as a relentless and bloody civil war rages on in Syria, more than 4 million Syrians have fled the country, while over 7 million have been internally displaced. Many of these refugees have fled to Europe, where the influx has triggered a massive crisis, the likes of which have not been seen since the end of World War II.

Several studies in the past have attributed the conflict, at least in part, to a series of severe droughts that have gripped the country since the late 1990s. Now, a new report from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies further bolsters the claim that anthropogenic climate change-induced drought may be one of the root causes of the conflict in the region.

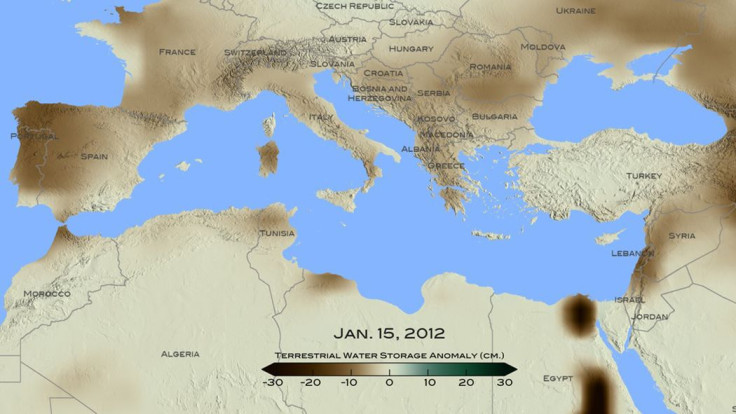

The study, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, states that the recent drought that began in 1998 in the eastern Mediterranean region — which includes Cyprus, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria and Turkey — is likely the worst drought to affect the region in 900 years, and that human-induced climate change was a contributing factor.

“The magnitude and significance of human climate change requires us to really understand the full range of natural climate variability,” lead author Ben Cook, a climate scientist at NASA, said in a statement released Tuesday. “If we look at recent events and we start to see anomalies that are outside this range of natural variability, then we can say with some confidence that it looks like this particular event or this series of events had some kind of human caused climate change contribution.”

Previous studies have shown that before the start of the Syrian uprising in 2011, when nationwide protests erupted against President Bashar Assad, Syria experienced one of the most severe droughts in recorded history. The drought, which lasted from 2007 to 2010, reportedly triggered an exodus of nearly 1.5 million farmers to cities in search of food and work.

For the purpose of the latest study, Cook and his colleagues used the tree-ring record, called the “Old World Drought Atlas,” to better understand how frequently and how severe Mediterranean droughts have been in the past. Rings of trees both living and dead were sampled from all over the region — northern Africa, Greece, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and Turkey — and then combined with existing tree-ring records from Spain, southern France and Italy. This data was used to reconstruct patterns of drought geographically and through time over the past millennium.

The team concluded that the region is unlikely to have seen a drought of this magnitude in at least 500 years, if not closer to a millennium. In either case, it is well outside the norm of natural variability.

“The Mediterranean is one of the areas that is unanimously projected [in climate models] as going to dry in the future,” Yochanan Kushnir, a climate scientist at Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory who was not involved in the research, said in the statement. "This paper shows that the behavior during this recent drought period is different than what we see in the rest of the record.”

While the study focused its attention on countries around the Mediterranean, the impact of climate change is unlikely to remain restricted to the Levant region. A separate study, published Wednesday in the journal Lancet, provided a stark estimate of how climate change would affect agriculture and threaten food security.

According to the study, climate change’s effects on global food supply could lead to over 500,000 deaths by 2050 as people around the world — especially in low- and middle-income countries in the Western Pacific and Southeast Asian regions — lose access to good nutrition.

“Much research has looked at food security, but little has focused on the wider health effects of agricultural production,” lead author Marco Springmann from the University of Oxford said in a statement. “Our results show that even modest reductions in the availability of food per person could lead to changes in the energy content and composition of diets, and these changes will have major consequences for health.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.