ISIS Propaganda Campaign: Did The Islamic State Group Unintentionally Provide U.S. With Airstrike Intel?

The Islamic State group’s propaganda campaign could actually be working against them. When the U.S. military planned the aerial bombardments against the Sunni extremist group, it may have done so using location information ascertained from the militants’ vast array of self-published, open-source information. Civilians were, after all, able to pinpoint with great accuracy the location of ISIS tweets and social media posts.

Since the Islamic State group declared itself a caliphate in June after seizing large portions of Iraq and Syria, it has been actively publishing reports of its exploits and using social media, YouTube videos and digital publications to spread its message: Join us or die. It has proven to be an effective recruitment campaign, boosting its numbers to as many as 31,500 fighters from up to 80 countries.

“In the minds of the foreign fighters, social media is no longer virtual: It has become an essential facet of what happens on the ground,” said a report from the International Center for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence.

This attention to social media, while a successful tool for ISIS, may also be a boon for American officials. Intelligence officials could be tracking where members are physically located when they post online. Real-time Twitter updates and online documentations of their operations could also be providing much-sought -weapons like the Tomahawk missile in the airstrikes against the group indicates that the U.S.-led coalition does indeed have very precise information about ISIS facilities and key people.

The militant group published quarterly reports of its attacks in chronological order, which included a detailed list of all of methods, dates and locations, according to Vocativ. The report allows the reader to track several things, but most notably it would allow U.S. officials to track what kinds of weapons the group has access to, and where militants are stationed.

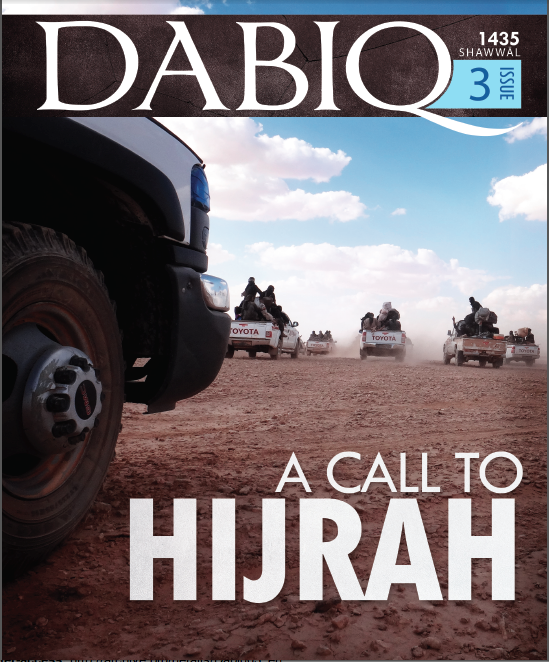

The quarterly report was not intended for an American audience, as it was published only in Arabic on one of the group's online forums. But the group also publishes a wide variety of material through its media center, al-Hayat, in a variety of languages, including English. The monthly magazine Dabiq is translated into English and then disseminated through various social media platforms, including Twitter. Each issue contains several pages of photo reports of the group's most recent attacks. The second issue mentioned ISIS attacks and ISIS community “events” in at least a dozen different locations across Iraq and Syria, including towns the militant group recently “liberated.”

“The soldiers of the Islamic State carry out an assault on the nusayrī (Syrian President Bashar Assad's) regime’s Division 17 army base outside the city of Ar-Raqqah and succeed in capturing it,” read one story in issue two of Dabiq. “During the course of the battle, two istishhādi [suicide] attacks were carried out by Abū Suhayb Al-Jazrāwī and Khattāb Al-Jazrāwī.”

The fact that this online propaganda has attracted the attention of American intelligence has been touted by U.S. leaders before. For example, Senator John McCain said in a June speech in the Senate that the social media campaign has provided insight that otherwise might be difficult to gain.

“ISIS social media published pictures of their fighters demolishing the sand berm, which hitherto marked the border between Syria and Iraq – an interesting symbolic gesture,” he said. “ISIS released footage of large numbers of weapons and armored military vehicles being received by members in Eastern Syria, confirming fears that the looted weapons would fuel the insurgency on both sides -- both Syria and Iraq.”

The State Department did not respond to the International Business Times' request for comment on whether it monitors ISIS’ online presence, but civilians have been doing so successfully. The crowd-funded journalism site Bellingcat appears to have done just that without the vast intelligence and surveillance technology the U.S. military has at its disposal. Founded by blogger Eliot Higgins, Bellingcat has posted a number of how-to guides providing simple instructions for users, hoping to authenticate images using only landmarks in videos; Panoramio, which extracts location metadata from digital images; and Flash Earth, a constantly updated service that compiles information from Google, Microsoft and other map providers.

Bellingcat determined the location of an Islamic State group training camp by examining a video the militants published of young fighters celebrating a graduation. Upon close inspection, researchers saw bridges in the background, quickly identifying it as the Tigris River in Mosul, Iraq.

Then, looking at another photo taken later, the Bellingcat team used the location of the street lights relative to the bridge to determine that the fighters (photographers in tow) had marched 1.8 miles away from the training camp. They compared the uniquely shaped streetlights to a Google Maps view of a bridge in Iraq’s Ninewa Province, ultimately deciding the bridges were one and the same.

As the group’s online presence grows, Islamic State fighters have started to realize that the social media war cuts both ways.

“There has been some evidence that they’ve tried to control this,” said Raffaello Pantucci, director of the International Security Studies program at the Royal United Services Institute.

When the militants released a video showing the beheading of U.S. journalist Steven Sotloff several weeks ago, reports stated that the video may have been leaked, as it did not come from the official ISIS media center. This prompted ISIS leadership to request that all videos be released in the same way, Pantucci said.

ISIS leaders does not seem concerned with supporters who spread the ISIS message on social media without ever going to the caliphate, Pantucci said. However, they do exert some control over those who are fighting on the frontlines.

“For those who have an online presence and who end up there, they have to give over their passwords to the group,” Mubin Shaikh, a former Taliban recruiter who operated from his hometown of Toronto before becoming a national security operative in Canada, recently told International Business Times.

ISIS isn’t the only extremist group in Syria that has caught on to the dangers of social media. Wednesday, two of al Qaeda’s affiliates in Syria published statements commanding their fighters to turn off all radio and satellite communications. Not only would this eliminate the militants’ urge to live-tweet the U.S.-led airstrikes, but it would also hinder any monitoring efforts from coalition forces.

“I’m sure they’re concerned that phones are being monitored,” Pantucci said. “And I suspect they are.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.