Kenya Seeks Progress, Dreads Violence As Presidential Election Nears

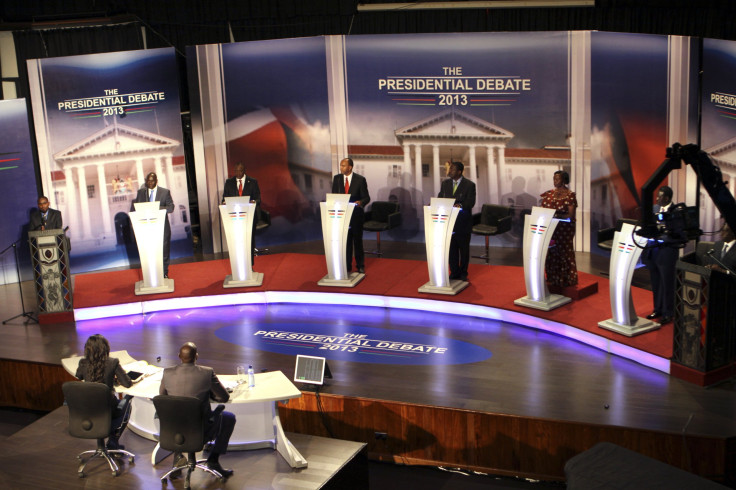

On Monday evening in the East African country of Kenya, millions of people tuned in to watch the biggest television event in the nation’s 50-year history: the first-ever presidential debate.

The cameras began to roll at 7 p.m. at a school in the capital city of Nairobi, and moderators Julie Gichuru and Linus Kaikai kicked off the broadcast by introducing the eight presidential hopefuls.

There were tiny hiccups in the presentation; the first candidate to walk onstage, Mohamed Abduda Dida, didn’t know where he was meant to stand. Only one contender, current Prime Minister Raila Odinga, took time to shake the hand of every opponent. The debate was intended to run until 9 p.m. but overshot its mark by an hour.

As the minutes ticked on, the dialogue picked up. Candidates addressed the three main themes: governance, security and social services. The moderators were adamant about time limits and quick to interrupt when debaters dodged questions. Voters got an unprecedented chance to see all of their presidential candidates together, making their cases and trading fire in real time.

And once the event was over, Kenyans quickly warmed to the post-debate tradition of poking fun at each candidate’s performance.

The charismatic Dida was a big hit; his quips were shared widely via social media. A photo of a toothbrush missing its middle bristles went viral -- that jab was for the presidential contender James Ole Kiyiapi, who has a gap between his front teeth. And the heavy bags under candidate Paul Muiti’s eyes won him an unflattering comparison to King Julien, an officious lemur in the children’s film “Madagascar.”

But one of the best zingers of the night came from Odinga, who seized the opportunity to dig into his fellow frontrunner Uhuru Kenyatta.

“I know that it will pose serious challenges to run a government by Skype from the Hague,” he said.

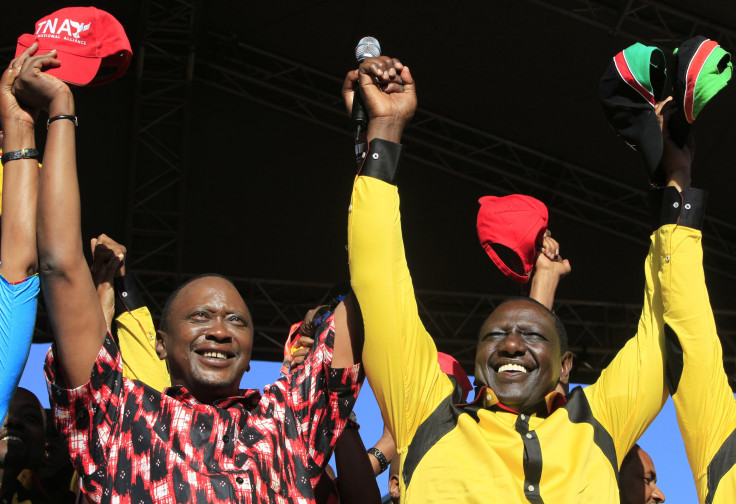

Kenyatta and his running mate William Ruto have both been charged by the International Criminal Court for inciting ethnic rivalries and violence during the 2007 presidential election. Both men, who were running separately, lost to current President Mwai Kibaki. They have been summoned to appear at a courtroom at the Hague in April and could face life in prison if convicted.

If Kenyatta wins the March 4 presidential election and is sentenced while in office, it could imperil Kenya’s relationship with the international community.

The ICC case is one of many very serious issues facing Kenya’s 42 million people in the run-up to this pivotal ballot; it is also a reminder of the bloody clashes that killed more than a thousand people and displaced hundreds of thousands more in late 2007 and early 2008. There are fears that a similar conflict will erupt again this year, throwing a wrench into the gears of Kenyan development at a pivotal moment in its history.

Dangerous Diversity

Ethnic clashes are already taking place in Kenya -- they abated after 2008, but have never died down completely. Tribal loyalties still play a huge role in local and national politics, and the presidential frontrunners Kenyatta and Odinga are both relying their traditional bases of support.

Odinga is of the Luo tribe, the people of Barack Obama's father; his running mate, current Vice President Kalonzo Musyoka, is a member of the Kamba community. Together, those ethnic groups comprise about one-quarter of the Kenyan population. Odinga’s party is the Orange Democratic Movement; his ticket is backed by the Coalition for Reform and Democracy, or CORD.

Kenyatta is of the Kikuyu tribe, Kenya’s largest group, which has a long history of wielding political power. He and Ruto, of the Kalenjin community, represent a coalition called the Jubilee alliance, which enjoys support from an ethnic bloc known as the Gikuyu (as Kikuyu is sometimes spelled), Embu and Meru Association, or GEMA. Kenyatta’s own political party -- which was founded last year as a vehicle for this campaign -- is The National Alliance, or TNA.

“Most people vote along ethnic lines, which means that Kenyatta has a head start,” says Ken Opalo, who grew up in Kenya and is currently a doctoral student in comparative politics at Stanford University.

“GEMA makes up about 30 percent of the population of Kenya, and Ruto’s Kalenjin community makes up about 13 percent. So if Jubilee coalition can organize its two biggest communities, Kenyatta will do very well. And he will have a higher turnout because the Kikuyu and Kalenjin communities are wealthier; they’ve been favored in terms of resource distribution and access to the media.”

But Odinga has nevertheless made a good showing in the national polls, most of which put him in the lead.

“There’s a sense that the Kalenjin and the Kikuyu have been in power for so long; the rest of Kenya also wants a piece of the pie,” said Opalo. “It is almost inevitable there will be a runoff, and then Odinga will have a better chance. He will likely get votes that had gone to [candidate Musalia] Mudavadi; with that and what he has now, he could beat Kenyatta.”

Analysts warn that prognostication is tricky this year due to a lack of precedent: this will be Kenya’s first general election since the passage of a new constitution. The 2010 document decentralized political power at the expense of the president, strengthened protections of human rights, and changed electoral laws so that candidates have less freedom to manipulate tribal loyalties. The constitution also bolstered the autonomy of the Independent Electoral and Boundary Commission, or IEBC, which oversees elections on the national and local levels.

Whether these changes will help to legitimize the election and quell public divisions is a matter of some contention.

Bloody Ballots

During Kenya’s infamous 2007 election, Odinga and current President Kibaki, a member of the Kikuyu community, went head to head. Kenyatta threw his weight behind Kibaki. Both sides played dirty during that pivotal campaign, using fiery rhetoric to stir up ethnic rivalries. It backfired after the election, especially since Odinga’s supporters suspected foul play. Deadly violence rocked the country; it came from all sides, and security officials often responded overzealously.

The crisis, which upended Kenya’s reputation for growth and stability, lasted for months until a deal was struck whereby Odinga became prime minister under Kibaki.

“Violence is not inevitable this time,” said Gabrielle Lynch, an associate professor of politics at the University of Warwick in England whose research has focused on Kenya.

“We could see an election that is relatively free and fair and peaceful, but it’s dangerous to be complacent. The election right now is neck-and-neck; both sides have reason to believe they can win. You can imagine scenarios where there could be significant levels of violence, for example if there was another dispute over the results.”

Already, misunderstandings about the electoral process threaten to undermine public trust in the democratic process.

“People’s experience of the electoral process may differ from their expectations,” said Lynch, pointing to a recent report from the IEBC revealing that 87 percent of eligible voters expect the ballot to be electronic -- in fact, it will be a simple paper ticket.

“Many Kenyans also believe that the voting process will not take as long as it has in years past, but actually it’s likely to take longer. Many believe the results will be announced more quickly than they’ve been, which is not necessarily the case. In short, people have certain expectations as to how voting will go ahead, which may not be met. And if you have a result that isn’t what some people expect, you could have a situation where people question the credibility of the election -- especially given high levels of public skepticism about politicians.”

Down To Business

Fears of violence due to tribal divisions are running high in Kenya, and this has the unfortunate side effect of sidelining the policy platforms that set each candidate apart.

“The main issues include things like education, jobs, economic development, land development and security,” says Lynch. “There’s also the issue of the new constitution and how that will work in practice, in terms of political inclusion.”

Both frontrunners vow to tackle corruption and further development, which are major issues for the Kenyan people.

“Broadly speaking, Odinga has been the champion of reform,” says Opalo. “He’s seen as the guy who fought for the new constitution. [Regarding] older issues like land distribution and economic malpractice, he’s seen as wanting to revisit some of those issues. Kenyatta, on the other hand, has focused on building a new Kenya.”

Though Kenya’s is the largest economy in East Africa with a GDP of about US$34 billion, most citizens live in poverty and unemployment is around 40 percent. But the economy, which relies heavily on agriculture, has seen growth over the past few years, and there is great potential for more. The Kenyan population is young, exports are diversifying, and political progress since 2008 is apparent. International investors -- when not deterred by ethnic clashes -- are recognizing these advantages.

On the other hand, corruption remains one of the most endemic problems in Nairobi, though Kibaki and all eight of this year’s presidential candidates have vowed to address it.

If transparency is truly on Nairobi’s list of priorities, Monday’s presidential debate was a good start -- with any luck, it could signal the beginning of lasting change. The moderators took pains to champion Kenyan unity before candidates first appeared, and then again after the contenders had made their closing statements.

Such proclamations are easier to make in urban centers like Nairobi, where different ethnicities mix on a daily basis. These days, violence poses more of a threat in rural areas and outlying villages where tribal identities are integral to the fabric of society.

But if March 4 is a day of relative peace, it could be the start of a fresh new chapter for Kenyan politics.

“What we do all agree on is this is great nation,” said the debate moderator Gichuru as the candidates stepped away from their podiums on Monday night. “Indeed, Kenya is poised for incredible growth.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.