Mali’s Other Crisis: Slavery Still Plagues Mali, And Insurgency Could Make It Worse

The conflict in the West African country of Mali erupted onto the international stage late last week, when it became the theater for a new Western offensive against Islamist insurgents.

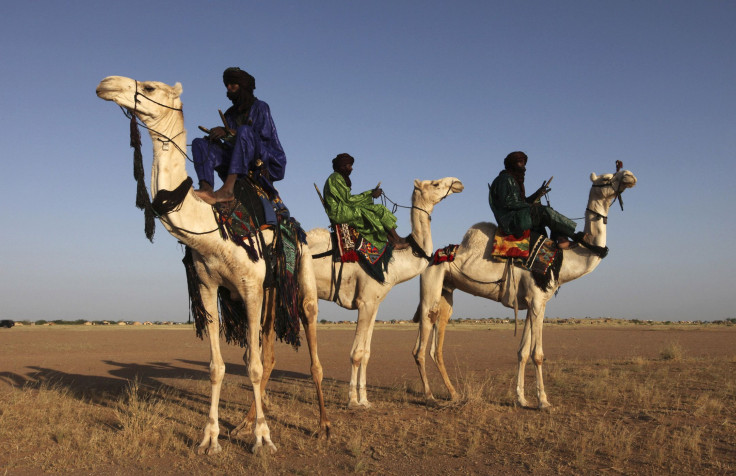

Early in 2012 the Tuaregs, a nomadic group native to the region, began asserting control over communities in northern Mali. On their heels came several militant Islamist groups that took over the area and are now the target of a French military intervention. Mali is also suffering from an unstable government in the capital city of Bamako, which has never recovered from a military coup that unseated the former administration in March.

But for two decades before all that, Mali was a stable democracy -- one of few in a tumultuous and under-resourced region.

Or so the story went. In fact, not all citizens enjoyed equal rights in this country of 16 million. Hundreds of thousands were -- and are -- victims of modern slavery, and the recent upheaval there has thrown a wrench into international activists’ long-running efforts to put an end to the practice.

Force of Habit

Slavery has been a reality in West Africa for centuries. Mali formally outlawed it when it became independent from France in 1960, but the rule is toothless since slave ownership was never criminalized.

The practice of slavery long has been a cultural norm in many Malian communities. As in neighboring Mauritania, slaves and slave owners are often described in terms of “black” and “white,” since slave descendants tend to have black African roots and their masters are typically of lighter-skinned Berber ancestry. But in fact, members of both groups have varying skin tones, and ethnicities are sometimes mixed due to masters raping female slaves.

According to Temedt, a Mali-based advocacy program, about 200,000 people are currently enslaved in the country and about 600,000 more are slave descendants under some form of control even though they live separately from their masters. Temedt works with Anti-Slavery International, a London-based human rights organization, to help free victims of slavery and then assist them in the transition to independence.

“We’re mainly working with ethnic Tuaregs, who have a very strong hierarchy including nobles, warriors and slave classes,” said Anti-Slavery International’s Africa Program Coordinator Sarah Mathewson, noting that slavery exists among other Malian communities as well.

Ending slavery is more complicated than it seems, since it is not only masters who are wedded to the system. Often, slave themselves have no desire to escape their servitude.

“I think for many people in that situation, the idea of leaving or escaping wouldn’t even occur,” says Mathewson. “They’re given no sense of their own agency; they’re in a state of total submission. And masters often use religion to further indoctrinate people, saying it’s God’s will they should be enslaved.”

To change these deep-seated attitudes, it is necessary to convince both slaves and masters that they can function outside the parameters of their dependent relationship. But that case is harder to make in times of turmoil, so Mali’s recent crisis has dialed back progress for anti-slavery activists.

Nowhere to Go

The Islamist insurgency in Mali’s north has turned things upside-down for many slaves and slaveowners.

“When the trouble started early last year, we had reports that lots of masters were leaving the region, and the people who had been considered slaves came forward to our partners saying, ‘We don’t know what to do; our masters left and we have nothing.’ They’d essentially been abandoned,” says Mathewson.

“That was a very difficult time. A lot of those people have made their way to refugee camps where they’ve gotten back in contact with their masters, or they’ve just been left vulnerable because of poverty and the lack of resources in the region.”

To make matters worse, the insurgents have imposed a harsh version of Shariah, or Islamic law, across northern Mali. They mete out some brutal punishments for citizens in perceived violation of Quranic codes, including floggings, amputations and executions. And slave descendants have often been the victims of those punishments, since they are largely vulnerable and unable to retaliate.

Slavemasters, too, take advantage of turmoil -- which includes widespread displacement -- to acquire new labor as necessary.

“We had one case in September of people coming to a village of slave descendants and taking 18 children that they wanted to keep as slaves,” says Mathewson. “The children’s families were completely bereft and couldn’t do anything. The slaveowners showed up and just took them.”

Progress Pending

With the security crisis still unfolding in northern Mali, many international efforts to free slaves and help them adapt have been put on hold. French airstrikes are churning up dust in some of Mali’s most vulnerable communities, putting the focus squarely on containing Islamist militants while leaving anti-slavery initiatives in limbo.

Ibrahim Ag Idbaltanat, a slave descendant who now runs Temedt, told The Guardian that the situation has only gotten worse in recent months.

"We are under suspicion from both the government and the rebels," he said. "Old scores are being settled and anti-slavery activists who have created a lot of enemies feel the threat of violence. We challenged the state and slaveowners, so now we face threats as there are slavemasters among the rebel groups."

Temedt and Anti-Slavery International had 17 legal cases regarding slave freedom under way in northern Mali that had to be suspended indefinitely as the insurgency unfolded. Advocacy and lobbying efforts still continue, but slave descendants on the ground in Mali are struggling to adapt in these tumultuous times.

“We just know that they are absolutely the most vulnerable people in that region at the moment,” says Mathewson. “They are the ones who don’t have the means to flee, who don’t have influence over the distribution of aid, who don’t have a voice in Mali.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.