Mitt Romney: 'Corporations Are People' - Is He Right? The Legal Background

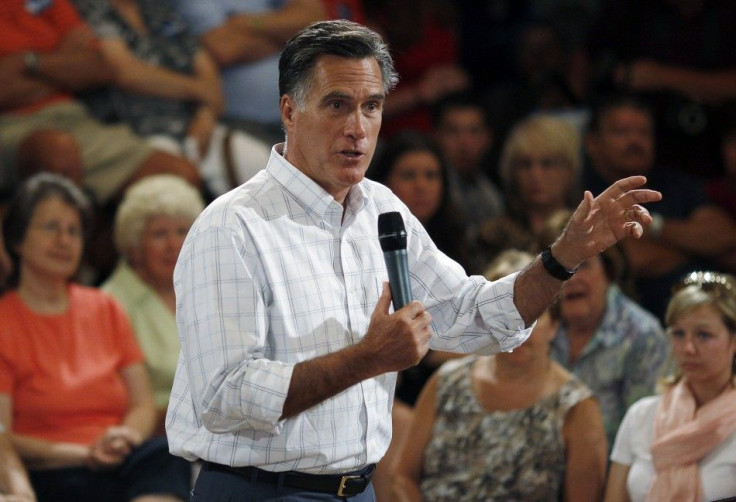

In what will likely become an endlessly replayed gaffe, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney on Thursday defended his pledge to not raise taxes by telling an audience at an Iowa state fair that, "corporations are people, my friend."

The remark gave sound bite-ready ammunition to Romney's opponents, with the Democratic National Committee sending out an e-mail response almost immediately. But while Romney was essentially endorsing the old Republican tenet that corporations are made up of people whose wealth then spreads to everyone else, he unwittingly touched on something else entirely: the ongoing legal debate over what rights we should give to people who aren't human -- from corporations to fetuses to, perhaps someday soon, machines.

The Corporation As Person

What is a person is not just an abstract concept for philosophers to ponder. It is has been a central question in deciding what constitutes a legal actor, someone (or something) who the law can protect or prosecute. One interpretation informed the Citizens United v Federal Election Commission 2010 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, which determined that corporations have the same free speech rights as people and can therefore spend as much as they like on campaigns.

But the idea is not new. From contentious 18th century debates about the legal status of slaves to the contemporary furor over corporate speech and abortion rights, being labeled a person has profound implications.

Of course, no one is claiming that a multinational corporation or an in utero fetus should get the same set of rights as a 30-year-old person who pays taxes and votes; legal personhood falls on a spectrum. There are gradations, and non-human being persons gradually accumulate legal rights and responsibilities that are explicitly granted to them by Congress or the courts. Legally, it is more accurate to think of a "person" as a metaphor used to designate a certain type of object of the law.

"Legal personhood is basically shorthand for saying the law recognizes this actor as a legal actor," said Daniel Greenwood, a law professor at Hofstra University. "So, for example in admiralty law boats are legal persons. In international law only sovereigns were considered legal persons until the second World War."

But the metaphor is a potent one, and it can give rise to a problematic tendency to try to equate legal personhood with humanity. The decision of whether or not to afford an entity constitutional rights is to a certain extent a value judgment. It affects real, indisputably human people: giving corporations more rights means they can better defend themselves against lawsuits by individual people; abortion laws force states to strike a careful balance between the health of the mother and the health of a human (but not yet person) fetus.

An anonymous Harvard Law Review paper sums it up succinctly: "this metaphor reflects and communicates who 'counts' as a legal person and, to some extent, as a human being." When Citizens United established corporate spending as an inviolable tenet of free speech, critics charged that things had gotten out of control.

"In the case of corporations it's a metaphor that's wrong," Greenwood said. "It's wildly inappropriate. There's never a reason to imagine that an organization is going to work the same way as a human being."

A good starting point for examining societal values through the lens of personhood would be antebellum America, where a fluid, sometimes contradictory understanding of whether slaves were legally persons reflected the moral contortions of a debate that would later tear the country asunder. Slaves were not persons in the sense that they were chattel, or property, that could not vote or protest being shackled and traded. But they were persons in the sense that they could be prosecuted for crimes.

Paradoxically, the passage of the 14th Amendment ensured that slaves could no longer be deprived of their rightful legal status as human beings, but it was also invoked in a series of landmark cases that conferred a host of rights on corporations. An amendment meant to ensure equality would bolster the outsize influence of corporations, which critics say has come at the expense of people.

A Key 1818 U.S. Supreme Court Decision

An 1818 U.S. Supreme Court decision was the first to recognize a corporation's ability to own property and to enjoy the constellation of rights that go along with it, defining a corporation as an "artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law." But the 1886 case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad took things a step further when the court affirmed that the 14th Amendment guarantee of equal protection covered a railroad company fighting against tax discrimination.

Curiously, the court had almost nothing to say on what, in retrospect, was a seismic shift. The headnote for the case stated only that, "The court does not want to wish to hear argument on the question of whether the provision of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations. We are all of the opinion that it does."

More than a century passed before Citizens United, but the precedent for anthropomorphizing corporations was set. For example, a 1977 case gave corporations 5th Amendment protection against double jeopardy in part by suggesting they would otherwise experience "embarrassment" and "anxiety." The courts have extended virtually every part of the Bill of Rights to corporations, though Greenwood wryly noted that a Second Amendment case has never been litigated.

Greenwood said that a basic argument for seeing corporations as persons with constitutional privileges derives from a "fetishism of the rights," essentially a sense that the more free speech, the better, no matter who is speaking. He is not alone in pointing out the danger of collapsing legal distinctions between corporate and human persons.

"Too frequently the extension of corporate constitutional rights is a zero-sum game that diminishes the rights and powers of real individuals," attorney Carl Mayer wrote in a paper on corporations and the Bill of Rights. "Equality of constitutional rights plus an inequality of legislated and de facto powers leads inexorably to the supremacy of artificial over real persons."

This tension between different types of persons, or different definitions of a person, is also on display as an emboldened currently Republican-led U.S. House of Representatives seeks to limit abortion access. Roe v. Wade staked its claims to the 14th amendment rights of women, but questions about whether a fetus is a legal person -- or, more accurately, when -- preceded Roe and continue to shape the debate.

"At the time the words [of the Constitution] were written they did not seem as problematic as they do [it does] today," said University of Kansas Law Professor Douglas Linder. "I think what we're dealing with is something that's developing and is becoming increasingly human and increasingly is taking on the attributes of personhood, and there is not going to a bright line test that everyone agrees to when in fact there is personhood here."

In 1884, a woman tried to sue her city, claiming a poorly maintained road had caused her to fall and miscarry. She lost her case, and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes reasoned that a fetus had "no separate existence," and thus could not have any legal recourse. A 1964 case diverged from that decision by awarding damages to a woman whose baby was injured while still in utero. The result was that tort law gave some legal rights to fetuses injured in utero.

State laws on abortion vary widely from state to state, something that reflects deep ambivalence about the personhood of a fetus. A deeply controversial (and subsequently withdrawn) law that would have made killing someone attempting to harm a fetus "justifiable homicide" in South Dakota essentially declared that a fetus had the same value as the life of, say, a doctor. Many states still have statutes on the books prohibiting "feticide," or the destruction of a fetus by any method other than legal abortion (though this is about the health of the pregnant woman, not just that of the fetus).

In her illuminating book "Is the Fetus A Person? A Comparison Across the Fifty States," Claremont Graduate University professor Jean Schroedel described how Roe v Wade had the unintended effect of clearly establishing a woman and her unborn child as separate legal entities. Roe v Wade adopted a three trimester framework in which the state could only regulate abortions in the third trimester, so that it could "promote its interest in the potential of human life."

This meant the state could override a mother's wishes in order to safeguard the potential life of the fetus. The third trimester was chosen because it contained the period of "fetal viability," a time when a fetus could survive outside the womb -- in other words, when it is sufficiently a person to merit legally protection.

"The Court's trimester framework established a precedent that viewed the interests of mother and fetus as adversarial," Schroeder wrote. "The constitutionally protected rights of women are to be balanced against the state interest in the health and welfare of the fetus."

Linder said that such considerations were of the type that the men writing the Constitution "never anticipated" -- they thought of persons more in the sense of someone who could be counted in the census. If they could not have foreseen the legal morasses of corporate or fetal personhood, there's no way they could have seen Watson coming.

Could Computers Become Legal 'Persons'?

For many people, the sight of a super-intelligent computer defeating humans on the television game show "Jeopardy" conjured up the familiar science fiction scenario of intelligent machines eclipsing their human overlords. But Lawrence Solum, a professor of law and philosophy at the University of Illinois, saw something much more plausible. He said that the type of technology Watson employs raises the "not all that remote" prospect of machines or computer programs gaining some basic legal recognition.

As an example, Solum said that humans could create a program entrusted to make investment decisions, noting that many stock trades are already electronically automated. This program could in that sense be a trustee making legally binding decisions -- and if it breached its contract, the program would be legally responsible.

It may seem absurd to hold a machine liable for what it does. After all, it is simply doing what its programmers told it to do, right? Not necessarily. Solum said it is a common misconception that Watson had a finite set of instructions that constrained its responses -- rather, Watson built a "semantic web" out of a vast collection of data, that it combined into responses. The same rules could apply to an investment program, or to a whole range of machines that could act with something like autonomy.

"This is the way human beings work," Solum said. "The brain is not a structured set of instructions, the brain involves massive numbers of connections and systems of pattern recognition. Machines can do that, too. They can be programmed so they behave like neural networks behave, so they can learn to do new things. They can develop capacities that their programmers didn't have and that their programmers didn't know that they would have."

Or their lawyers, for that matter.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.