Rolling Stones At 50: What A Drag It Is Getting Old

ANALYSIS

Fifty years ago Thursday, a group of raw young musicians performed at a dingy club in London in front of a small crowd of blues enthusiasts. If those green lads had not eventually become the Rolling Stones, one of the biggest musical acts in history, that evening’s performance would have been relegated as an unimportant, mundane event and largely forgotten.

But it was the start of something huge.

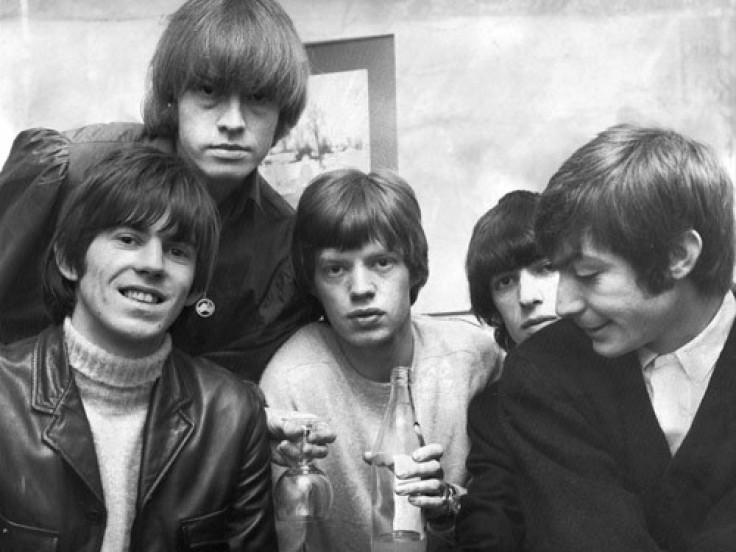

On July 12, 1962, two boys from the provincial Kentish town of Dartford, Michael ‘Mick’ Jagger and Keith Richards, were joined onstage at the Marquee Club in Oxford Street by four other hungry aspiring young musicians: Brian Jones, Dick Taylor (not to be confused with Mick Taylor), Mick Avory and Ian Stewart. They billed themselves as The Rollin' Stones (for the very first time in history) and played a number of songs by American rock stars Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley (somewhat in defiance of Jones’ desire to play pure blues).

While the others would later go their own ways or be dismissed (except for Stewart, who was the unofficial sixth Stone and played keyboards on many records and tours), Jagger, Richards, and Jones would form the core of what became one of the most popular rock bands of the 1960s, later inviting drummer Charlie Watts and bassist Bill Wyman.

However, on that summer night in July 1962, the Stones had “no expectations” that they could even make any much money playing such gigs, much less metamorphose into a global cultural iconic symbol of youth, wealth and licentiousness.

In fact, the Stones were not even the featured act that night – rather they opened for a blues singer named Long John Baldry.

At that time, all they had was a shared love for the music of black America, a culture that seemed remote, exotic, and incredibly appealing to bored, restless white kids who grew up in the dreary, grim, grey, straight-laced, class-conscious world of post-war Britain.

From such humble beginnings, a massive revolution eventually erupted and rippled over much of the globe.

But what was England like in that long-ago period?

Beneath the surface things were indeed changing and percolating, but at face value, Great Britain remained seemingly trapped in traditions rooted firmly in the past.

The devastating Second World War, which ended only 17 years before, was a fresh memory for millions of Britons – indeed, places like the East End of London were still pockmarked by bomb craters and other detritus of Nazi raids.

Queen Elizabeth, only 36 years old at the time, had been on the throne for a decade, while Harold Macmillan, a man born during the reign of Queen Victoria, served as Prime Minister. (His government would collapse the following year as a result of the monumental Profumo scandal).

Across the ocean, a charismatic young Irish Catholic named John F. Kennedy was president of the United States, a country asserting itself as the world’s dominant superpower and embarking on the grand adventure of space exploration -- astronaut John Glenn was the first American to go around the earth, just five months prior, setting up a race to the stars with the Soviet Union.

By the end of 1962, Kennedy and his nemesis, the president of Russia Nikita Khrushchev, would bring the planet to the brink of an atomic war over a little piece of real estate called Cuba. (By the end of the following year, Kennedy would be murdered by an assassin’s bullet).

Within England itself, slow, gradual changes were afoot.

Just one month prior to the Stones' public debut, a group calling themselves The Beatles made their first official recording at EMI Studios (about three miles north of the Marquee). The Beatles were well known in the northern town of Liverpool and the waterfront of Hamburg, but had yet to prove they could conquer London.

They, too, were undergoing personnel changes – within one month the handsome drummer Pete Best would be replaced by the homely Ringo Starr, an event that outraged all the fine young lasses of Liverpool, but barely mattered anywhere else. (The Beatles' former bassist, Stuart Sutcliffe -- who really could not even play the instrument – died of a brain hemorrhage earlier in the year).

It is doubtful that the Beatles and Stones had even heard of each other in July 1962, although within two years they could become great rivals and the only legitimate answers to the question: “Who is the greatest rock band in history?” However, the two groups were vastly different from each other – The Beatles favored a wide array of musical genres, including American rock, rhythm-and-blues, Motown, but also country-and-western, pure pop, Broadway musicals and even English dance hall. The two undisputed leaders of The Beatles, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, could even write their own songs.

In stark contrast, the Stones championed hard Mississippi and Chicago blues (with a dash of Berry) and did not dream of composing their own songs yet.

Musically, the Beatles and Rolling Stones were inadvertently stepping into a vacuum – the biggest rock star in the world, Elvis Presley, was inducted into the army in 1962. His career as an innovative and compelling musical artist would essentially be over. The American rhythm & blues music which the Beatles and Stones loved was not popular with the mainstream (white) audience on either side of the Atlantic (yet) .

Indeed, consider that the most dominant UK singing star in 1962 was the sterile and sexless Cliff Richard, while the biggest selling single of the year was “I remember you” by Frank Ifield, whose specialty was (believe it or not) yodeling.

While many working-class white English lads in 1962 favored the ‘Teddy Boy' look (tight drainpipe jeans, tough facade, leather jackets, etc.), the youth culture as we understand it now did not really exist. The cost of LPs (record albums) was prohibitively high for most British youth, forcing them to gobble up '45 singles of the latest hits instead. (The LP market at the time was geared towards the 'easy listening' music favored by adults).

Moreover, if a young lad or lass could not afford to buy a single and wanted to listen to rock and roll, they might have to tune in to “pirate” radio stations like Radio Luxembourg, since BBC radio generally avoided playing that type of “Negro” music.

The drug culture which would sweep over Western youth within a mere four of five years did not really exist either. The Beatles never smoked marijuana until they were introduced to the herb by Bob Dylan in a New York City hotel suite more than two years hence.

While Britons then had not yet become familiar with drugs like cannabis or cocaine, they smoked tobacco in massive amounts.

In March 1962, the Royal College of Physicians, Smoking and Health issued a report linking cigarette smoking with lung cancer. Many failed to heed such warnings – at that time, almost three in four men and two-fifths of women in the UK smoked (including all of the Beatles and Stones). Now, in 2012 about one-fifth of the British populace light up.

The sexual revolution would also have to wait, given that abortion was illegal, homosexuality was a crime and the “pill” was a few years away from widespread availability. Generally speaking, men worked, women stayed at home, couples remained married forever, and that was that (at least outside the wealthy enclaves of London).

Indeed, the infamous novel “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” by D.H. Lawrence was removed from the banned list of books just a few years prior, following a highly-publicized obscenity trial.

And as “dirty” books were becoming available to the public, dirty air still plagued Britons – pollution in London was so thick that air and train transport were often cancelled due to atmospheric conditions and thousands of people became ill (750 people reportedly died from respiratory illnesses due to the deadly smog in 1962).

Air travel and taking vacations to foreign lands were out of reach for the vast majority of people; one-third of the population did not have indoor plumbing or hot running water. Homes were still largely heated by coal. The class system remained as rigid as in Victorian times – the poor and working class had no hope of moving up on the social ladder, and a university education was beyond the aspirations of most young people.

The meals people ate were old-fashioned British staples – like Yorkshire pudding, roast beef, sausages and mash and fish and chips. Such “exotic” dishes as curry and kebabs were practically unknown.

But there was a cultural scene in London that was starting to offer new forms of entertainment to both challenge and provoke the masses. The 1956 play by John Osborne, “Look Back in Anger,” startled the public with its gripping portrayal of working-class English life, leading to a flurry of so-called realistic “kitchen sink dramas” about the lives of ordinary people struggling through life.

Indeed, just one month prior to the Stones’ debut at the Marquee, a television show was introduced that would become the most wildly popular program in British history and become a touchstone for the decade just as important as the Beatles and Stones (at least in Britain). “Steptoe and Son” was a grim, realistic, but very warm and entertaining portrayal of a desperately poor father-and-son rag-and-bone (junk) team. The show would last for more than a decade, developing a fanatic base of viewers. (By the early 1970s, U.S. television would create their own version of the program, calling it “Sanford and Son”).

Other changes were also in the wings.

In the summer of 1962, Britain was still an overwhelmingly white nation, but even this was changing. Since the end of World War II, tens of thousands of Commonwealth immigrants moved to the ‘Mother Country’ from such far-flung places as India, Pakistan and Jamaica to fill a labor shortage in the factories, foundries and public transport.

By April 1962, the presence of ‘coloured’ immigrants had caused the government enough alarm to pass a law that significantly reduced the free immigration of Commonwealth citizens to the UK without proof of employment. (The Notting Hill race riots of 1958 also alarmed the government and public.)

In the coming years, however, the rising numbers of immigrants would lead to tremendous social upheaval and political turmoil. But in 1962, blacks and Asians were rarely seen outside of the big cities.

The once invincible British Empire was also fragmenting -- in 1962 alone, Jamaica, Uganda, Trinidad and Tobago all became independent states following in the heels of Tanzania, Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Ghana in recent years.

The sun was clearly setting on Winston Churchill’s beloved empire (incidentally, Churchill was still alive in 1962).

But not everything was gloomy in Blighty – the jobless rate was below 3 percent.

British historian Dominic Sandbrook (who was not even alive in 1962) wrote in a recent editorial: “There were only 6 murders per thousand people in 1962; now there are 13. Some 20,000 people were in prison then; now there are 84,000.”

But Sandbrook pointed out some surprising developments over the past half-century.

“The national debt today stands at a record 800 billion pounds -- which is why the newspapers are so full of doom and gloom,” he said.

“Fifty years ago, national debt stood at just 26 billion. But… if you convert that into modern money, you get a figure of 1,500 billion [pounds] – more than twice the level today, reflecting the massive financial obligations left over from the Second World War, and the cost of keeping so many British troops scattered across the Empire.”

Similarly, he added, the average yearly salary for an Englishman in 1962 was about 550 pounds a year.

“But in modern money, that works out as about 23,000 pounds – only two thousand pounds less than the average Briton earns today,” he noted.

This was the world the young “Rollin’ Stones” found themselves in the summer of 1962. In their wildest dreams they could not have imagined what their near-term future would hold… or that they would still be together making music (with several more personnel changes) after an astounding fifty years.

In 1962, it was not even certain that rock music would last… some dismissed it as a “passing fad,” making it impossible for anyone to think they could actually make a living out of it.

But dozens of records and billions of pounds later, The Stones have outlasted all their critics and disproven the concerns that rock music would vanish.

Jagger and Richard are now almost 70 years old, wealthy and famous beyond all comprehension. Many of their contemporaries have long since retired or died – their longevity and success has been nothing short of miraculous. (Many people, of course, think that they should have retired long ago since rock-and-roll is after all a celebration of youth).

Moreover, London is now a multi-cultural, cosmopolitan city that bears no similarity whatsoever with its 1962 version. But some icons remain: Queen Elizabeth, for example. And the Rolling Stones.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.