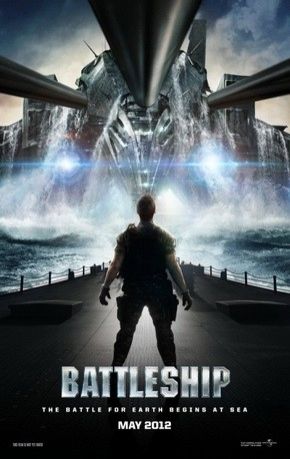

The Science Of ?Battleship,? A Nearly Completely Terrible Movie

While Battleship is not the worst movie ever made, it is a low-grade Transformers rip-off-at-sea that makes Independence Day look like Citizen Kane. And it gave this reporter motion sickness. But the film does have one big thing in its favor: It's not Battlefield Earth.

While Battleship's dialogue, character development and plot make very little sense, this 130-minute Hasbro commercial-slash-U.S. Navy recruiting ad does have a toehold in scientific fact.

In the movie, scientists find a so-called Goldilocks planet, one that is not too hot or too cold -- one that seems just right for life -- and they decide to beam a signal to it. In recent years, scientists have discovered untold numbers of planets orbiting at the right distance from a star to fall temperature-wise within a potentially habitable zone. These satellites could contain liquid water and, if they're the right size, an atmosphere that might support life. A recent study estimated that there could be billions of these worlds in the Milky Way galaxy alone.

One scruffy scientist in Battleship predicts that if aliens come to earth as a result of the team's' attempt to make contact with the planet, it would be like Columbus and the Indians all over again.

Except this time we're the Indians, he says.

That helpful bit of foreshadowing is cribbed from physicist Steven Hawking, who has said that any aliens we get in touch with would likely just see Earth as a source of exploitable resources.

Whether or not aliens advanced enough to cross interstellar distances would be inherently malevolent or benign is a purely academic line of inquiry, according to Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the SETI Institute and one of the scientific consultants on Battleship.

But the idea that aliens would need to harvest Earth's resources -- such as water -- is laughable.

That doesn't make sense, because the universe has a lot of water, Shostak says.

(It's never really established what the aliens in 'Battleship' are after, by the way. The movie doesn't have plot holes so much as it has plot Marianas trenches.)

Even if aliens wanted to harvest Earth's water, it's a relatively dense substance. Moving water off the planet would require a lot of energy and expense, and it is one of the more challenging barriers to establishing permanent colonies on the moon, Shostak says.

When not listening for extraterrestrial life, Shostak helps inject more accurate science into television and movies by way of a National Academy of Sciences program called The Science & Entertainment Exchange, which links up the scientific and entertainment communities. He's already been a consultant for a number of big budget films besides Battleship, including the 1997 film Contact and the 2008 remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Shostak doesn't mind working on action films. Even the cheesiest science-fiction movie can get young people interested in science, he says.

What I hope to do is not just fix little technical details, Shostak says. He wants to encourage Hollywood types to use interesting new scientific finds, like the discovery of wandering orphan planets that are not orbiting any star.

They're still working on science they learned in the fifth grade, he lamented.

If scientists did find evidence of alien life on other worlds, SETI's standing policy is to not make contact until an international body like the United Nations decides on a course of action.

But realistically, as soon as news got out about extraterrestrial life, anyone with a radio transmitter could point it at the right coordinates and start beaming whatever they wanted at our new interstellar neighbors.

The question of whether or not we should attempt to communicate with other worlds is a moot point, Shostak says, because humanity has been sending signals into space ever since the first radio broadcast, and we are still sending out signals today.

Any society that's advanced enough to build a rocket ship and come to earth can easily pick up that leakage. There's no calling those signals back, Shostak says.

Besides, why worry? If interstellar travelers really did want to destroy us, it would be no contest.

It would be like the U.S. Air Force versus the Neanderthals. The Neanderthals might have some interesting characters, but they're not gonna win, Shostak says. (To clarify, we would most certainly be the Neanderthals in that scenario.)

So if E.T. is listening, why might he decide to pay Earth a social call?

The only thing we have that they don't have is our culture. Maybe they'll come for the poetry, Shostak says.

One doubts they will come for 'Battleship, though.

Post-script: this reporter assumed that one of the actors (hopefully Liam Neeson and not the wan excuse for a male lead) would at some point utter the line You sunk my battleship! -- perhaps while punching an alien.

This would be the payoff for enduring more than two hours of bewildering destruction, wooden acting and a soundtrack that chiefly consists of metal screeching emitted by a chorus of chalkboards being scraped in Hell.

No such consolation was offered.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.