The Year In Science: From Gravitational Waves To CRISPR, Here Are The Biggest Science Newsmakers Of 2016

2016 has been, to put it mildly, a complicated year. The same can be said about the world of science, which witnessed some of the biggest breakthroughs in decades, even as it provided several grim reminders about the impact of climate change on planet Earth.

Here are the biggest science newsmakers — both the good and the not-so-good — of the year:

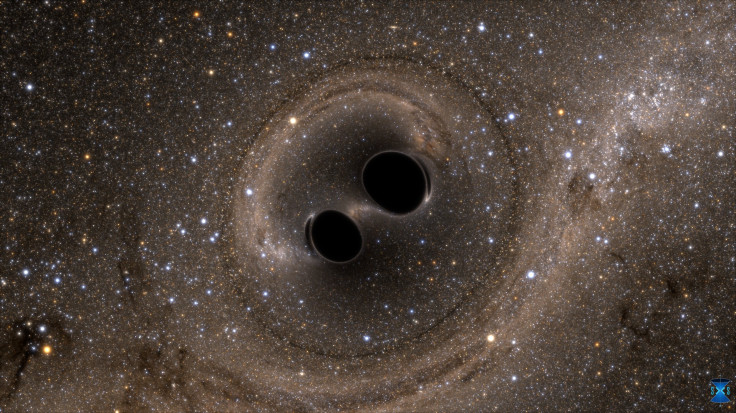

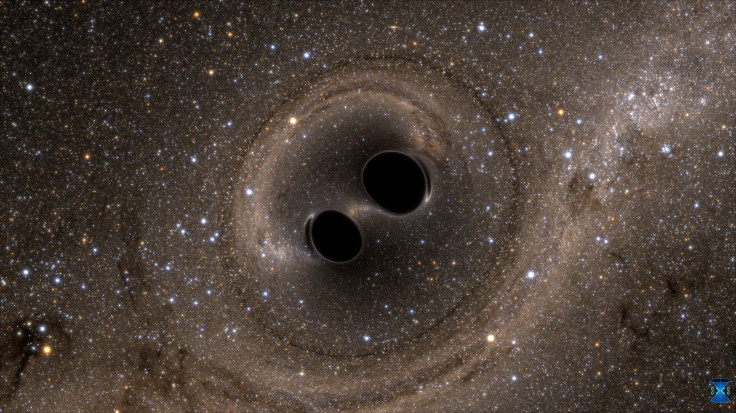

Ripples in Reality

One hundred years ago, Albert Einstein predicted that the collision of massive objects such as black holes and neutron stars can create “ripples” in the curvature of space-time. Earlier this year, scientists associated with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) discovered these distortions.

“The achievement fulfilled a 100-year-old prediction, opened up a potential new branch of astronomy, and was a stunning technological accomplishment,” the journal Science, which was one of the many publications that termed the discovery of gravitational waves “Breakthrough of the Year,” said in a recent statement.

Currently, all we know about the cosmos is what we have gathered from electromagnetic radiation such as radio waves, visible light, infrared light, X-rays and gamma rays. As a result, a lot of information remains hidden because such waves get scattered as they traverse space-time, and because the universe, in its infancy, was opaque to electromagnetic radiation.

With the discovery of gravitational waves, all this looks set to change.

Scientists believe that with enough gravitational wave detectors, they would be able to study objects and phenomena that would otherwise remain hidden from view, providing us with a “gravitational map” of the known universe.

Gene-Editing Revolution

News about the novel gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 continued to dominate headlines through the year.

In October, a group of Chinese researchers became the first to inject genes edited using the technique in a human subject — in this case, a patient with aggressive lung cancer. As part of the clinical trial, the researchers used CRISPR to disable genes in the patient that suppress the cell’s immune response, with the hope that doing so would allow the immune system to fight back against the cancerous cells.

Controversially, another Chinese team also used the technique to create HIV-resistant embryos. The embryos used, however, were created using non-viable human eggs, and were destroyed in three days’ time.

Meanwhile, efforts to use CRISPR in the U.S. and Europe were stymied due to ongoing patent disputes over who should own the rights to the invention. Human trials involving CRISPR in the U.S. and the European Union are expected to begin sometime next year.

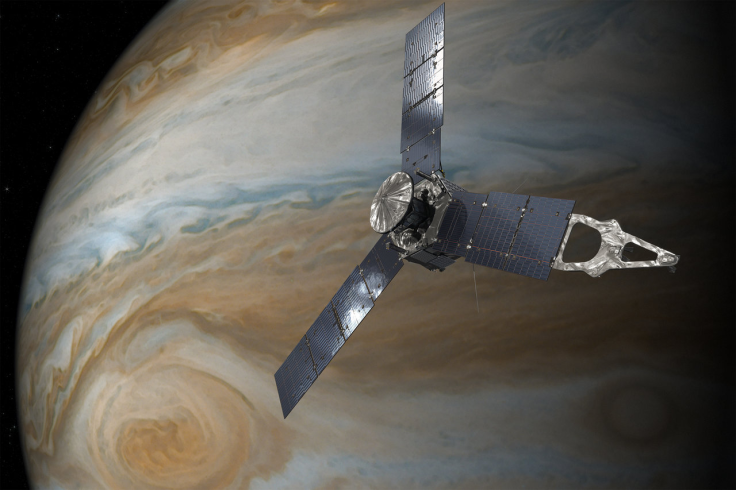

Knocking on Jupiter’s Door

After a five-year voyage during which it traversed nearly 2 billion miles of space, NASA’s Juno spacecraft entered into orbit around Jupiter on July 5, 2016. The spacecraft, named after the Roman god Jupiter's wife, will spend the better part of the next year trying to peer through the thick clouds surrounding the massive gas giant.

The primary goals of the $1.1 billion mission are to find out whether Jupiter has a solid core, and whether there is water in the planet's atmosphere — something that may not only provide vital clues to how the planet formed and evolved, but also to how the solar system we live in came into existence.

So far, Juno has carried out three close flybys of the gas giant, beaming back images of its poles and its gigantic southern aurora. At the end of its mission, the solar-powered spacecraft will dive into Jupiter’s atmosphere and burn up — a “deorbit” maneuver that is necessary to ensure that it does not crash into and contaminate the Jovian moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

The “Bump” That Wasn’t

For scientists at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), this year would definitely be tinted with disappointment — although the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) surpassed its 2016 run targets by a wide margin. A mysterious “bump” in data gathered by the collider’s CMS and ATLAS detectors during 2015 run, was, upon further analysis, found to be nothing more than a statistical fluke.

“It’s disappointing because so much hype has been made about it,” Tiziano Camporesi, spokesman for the CMS collaboration, said in August. “We have always been very cool about it.”

If the existence of the bump, which had hinted toward an unexpected excess of pairs of photons carrying around 750 gigaelectronvolts of combined energy, had been confirmed, it would have provided us the first direct evidence of a particle — roughly six times more massive than the Higgs boson — that would have broken the Standard Model of particle physics.

Man vs. Machine

The year witnessed another key milestone in the field of machine learning when, in March, an artificial intelligence program, named AlphaGo, developed by researchers at Google DeepMind defeated the reigning world champion Lee Sedol in the ancient Chinese game of Go.

While the rules of the game are simpler than those of chess, the overall complexity is much higher, making it, in the words of DeepMind co-founder Demis Hassabis, a much more “intuitive” game. While chess offers some 20 possible choices per move, Go has about 200 — in other words, the game provides more options than there are atoms in the universe, making AlpahGo’s achievement all the more impressive.

“Go is a game of profound complexity,” Hassabis explained in a blog post. “This complexity is what makes Go hard for computers to play, and therefore an irresistible challenge to AI researchers, who use games as a testing ground to invent smart, flexible algorithms that can tackle problems, sometimes in ways similar to humans.”

Another Earth?

In August, astronomers announced the discovery of an Earth-mass world in our cosmic backyard. The discovery promptly made the planet, named Proxima b, the prime candidate for the hunt of life beyond our solar system.

The planet orbits Proxima Centauri — a red dwarf that is the nearest known star to the sun. Its 11-day orbit around its parent star is much smaller than Mercury’s orbit around the sun, but, since Proxima Centauri is only about 12 percent as massive as the Sun, and way dimmer, the planet lies well within the “Goldilocks zone” — a region where the temperature is just right for liquid water to exist.

Two studies published in October further bolstered the case for Proxima b’s habitability. One of them, based on simulated models, suggested that the world is most likely an “ocean planet” similar to Earth.

The “Impossible” Engine

Electromagnetic drive, or EmDrive, shouldn’t work, but somehow it does. In November, scientists associated with NASA’s Eagleworks Laboratories revealed, in a peer-reviewed study, that they had succeeded in creating an experimental EmDrive capable of producing thrust of up to 1.2 millinewtons per kilowatt in vacuum.

Although an order of magnitude higher thrust can be produced using rocket fuel, the significance of the achievement lies in the fact that it shows the existence of something that current laws of physics tell us shouldn’t exist — you can’t drive a car by getting on the front seat and pushing the windshield.

So if this engine is impossible, as physicists repeatedly dismissed it prior to the publication of the study, how does it create thrust? Although the exact cause is yet to be determined, the best, and currently the only explanation relates to a controversial interpretation of quantum mechanics known as the pilot-wave theory, which, unlike the currently-accepted Copenhagen interpretation, states that subatomic particles do have fixed locations even when they are not being observed.

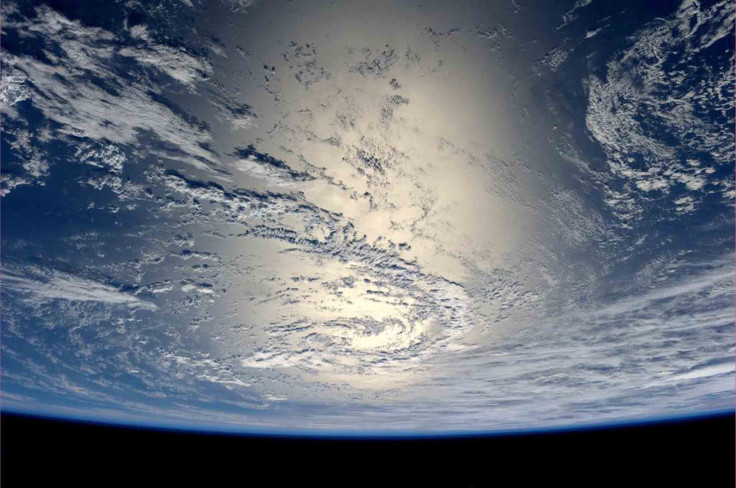

From Pole To Pole, Earth Feels the Heat

For Earth’s poles — the Arctic and the Antarctic — 2016 was a remarkably bad year. Driven by unusually high air temperatures, warm ocean and warm winds from the south, both Arctic and Antarctic sea ice extent dropped to record lows in November.

In November, Arctic sea ice extent averaged at just over 3.5 million square miles — 309,000 square miles below the previous lowest November on record. In the Antarctic, the average ice extent was 5.6 million square miles in November — over 380,000 square miles below the previous record low set in 1986.

For the Arctic, this was especially surprising, as sea ice in the region normally grows over the winter. This year, though, formation of ice was prevented by the unusually high sea surface temperatures in the Barents and Kara Seas — a phenomenon driven largely due to warm Atlantic water moving into the Arctic continental shelf seas. Some areas of the Artic even reported temperatures that were 20 degrees Celsius higher than normal

“These temperatures are literally off the charts for where they should be at this time of year,” Jennifer Francis, a research professor at the Rutgers University’s Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences, told the Guardian late last month. “The Arctic has been breaking records all year.”

An Unfolding Disaster

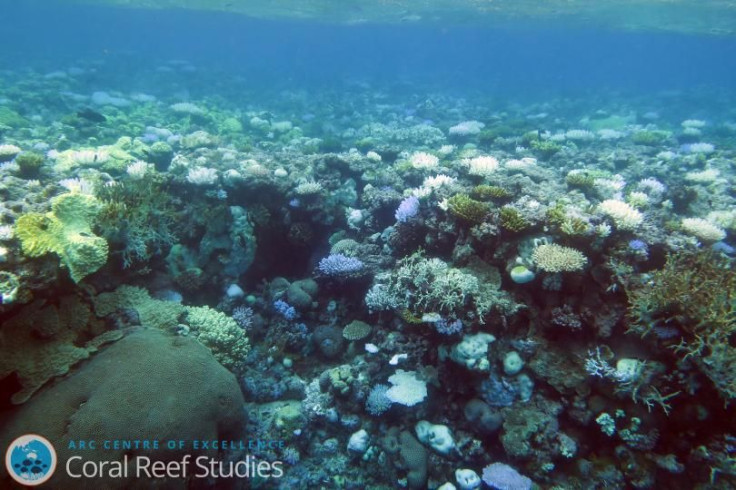

Beginning in March, the iconic Great Barrier Reef — the largest living structure on the planet — began grabbing headlines for all the wrong reasons. A survey carried out by scientists at the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority revealed a “substantial” level of coral mortality in the northern reaches of the reef.

Since then, several surveys have had brought to light a sobering truth — the Great Barrier Reef is currently witnessing the largest coral bleaching event ever recorded. The bleaching event — triggered by climate change-induced ocean warming and acidification — is the most pronounced in the northern regions of the reef, where an average of 67 percent of shallow-water corals have died over the past nine months.

Coral reefs, which are delicate marine biodiversity hotspots where corals grow in symbiosis with algae, become bleached when they are stressed due to a rise in ocean temperatures, acidity, or both, which expels the symbiotic algae living in corals’ tissues, causing them to turn completely white.

Scientists now estimate that it would take anything between 10 and 15 years for the bleached corals in the reef to recover.

Turning Point in the Fight Against Climate Change?

2016 is almost certain to go down as the hottest year on record. Given this backdrop, if there is a silver lining in the fight against climate change, it’s this — 2016 was the year when a landmark climate treaty, finalized in Paris last December, entered into force.

The agreement, which needed to be ratified by at least 55 parties accounting for at least 55 percent of global emissions, came into effect on Nov. 4 — 30 days after the European Parliament ratified it.

The long-term goal of the climate agreement, drafted during the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris in December 2015, is to keep the rise in average global temperatures “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above the pre-industrial levels, and pursue efforts to keep it within 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

In order to meet the aspirational goal, developed nations have pledged an absolute reduction in their emissions, while developing countries such as China and India have set deadlines to peak greenhouse gas emissions. The U.S., for instance, has pledged to slash its emissions by up to 28 percent of its 2005 levels by 2025, while China has promised to peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030.

However, given that global temperatures have already risen by almost 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), many experts have now expressed scepticism over whether targets can realistically be met.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.