Antarctic Sea Ice: 14% Loss Over 100 Years; Pine Island Glacier Melt Began Over 70 Years Ago

Even as human-induced climate change and global warming has been shrinking the polar ice cap at the Arctic at an alarming rate, sea ice on the South Pole behaved to the contrary and expanded for much of the last three decades, a phenomenon that has baffled scientists and one that is often used by deniers of climate change as evidence in support of their arguments.

And now, with two new studies published this week, understanding changes in Antarctic sea ice got even more complicated.

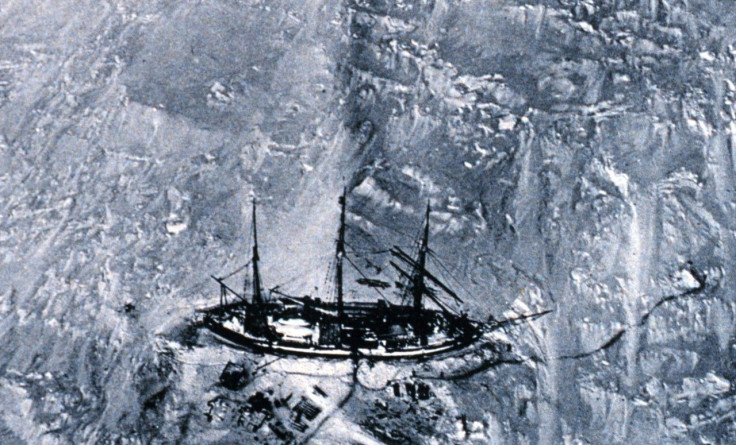

One study, published Monday in the Cryosphere journal, looks through the logbooks of early Antarctic explorers from the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1897-1917)” and compared the recorded observations of Antarctic ice from the time with satellite images from today.

Carried out by climate scientists from the University of Reading, United Kingdom, the study, titled “Estimating the extent of Antarctic summer sea ice during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration,” analyzes “observations of the summer sea ice edge from the ship logbooks of explorers such as Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton and their contemporaries during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1897–1917).”

The researchers estimate the extent of Antarctic summer sea ice is now at most 14 percent less than it was about 100 years ago, according to a statement released by European Geosciences Union, publishers of the Cryosphere.

They also suggest an explanation for the increase in Antarctic sea ice seen in the last 30 years.

Jonathan Day, leader of the study, said: “We know that sea ice in the Antarctic has increased slightly over the past 30 years, since satellite observations began. Scientists have been grappling to understand this trend in the context of global warming, but these new findings suggest it may not be anything new. If ice levels were as low a century ago as estimated in this research, then a similar increase may have occurred between then and the middle of the century, when previous studies suggest ice levels were far higher.”

The second study, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, explained that the thinning and retreat of the Pine Island Glacier in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has been underway for at least 70 years. The melting of the glacier and those of others near it is one of the biggest contributors to the rise of sea levels.

Titled “Sub-ice-shelf sediments record history of twentieth-century retreat of Pine Island Glacier,” the study was led by researchers from the British Antarctic Survey. A BAS press release said: “Seabed sediment cores obtained from beneath the floating part of Pine Island Glacier have revealed that a cavity started to form beneath the shelf prior to the mid-1940s. This allowed warm sea water to flow under the shelf, and cause it to lift-off from a prominent sea-floor ridge which held it in place. This strongly suggests that current retreat was initiated by strong warming of the region associated with El Niño activity.”

The finding is significant for at least two reasons. Study co-author Bob Bindschadler of NASA points one out about the long-term effects of climate phenomena: “A significant implication of our findings is that once an ice sheet retreat is set in motion it can continue for decades, even if what started it gets no worse.”

The other is that ice loss from the West Antarctica region is one of the biggest contributors to the rise in global sea levels and, but the factors responsible for the melting glaciers are poorly understood, creating large uncertainties in prediction models. Better knowledge of how and why these glaciers are shrinking and retreating could help with that.

Even while the sea ice in Antarctica has been mostly gaining the last few decades, it was revealed earlier this year that glaciers in West Antarctica were retreating at a pace faster than previously thought. And NASA said earlier this week the extent of Antarctic sea ice loss this year was the fastest since records began in 1979.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.