Australia Slammed For Upholding Policy Of Detaining Refugees On Nauru Island

The Australian High Court on Wednesday dismissed a claim that detention of asylum-seekers offshore in Nauru Island violated the Australian constitution and upheld its policy to hold refugees at processing centers there, reports said. The decision triggered outcry from the United Nations and several human rights groups, as it made way for 267 asylum-seekers to be deported from Australia to Nauru.

The plaintiff, a Bangladeshi woman identified only as M68 in court documents, entered Australia seeking asylum and was classified as an “unauthorized maritime arrival” before being sent to Nauru Island. She was returned to Australia due to medical problems where she gave birth to a child and filed the case to avoid being taken back to Nauru, Sydney Morning Herald reported. The 237 asylum-seekers, who may now be sent to Nauru, include 39 children and 33 babies, who were born in Australia.

Six out of seven judges ruled in the favor of holding the refugees in the offshore processing centers and ruled that the Australian government detaining the woman was authorized by a valid law, the Guardian reported. They also said that a deal between the two countries did not violate the constitution.

“The detention in custody of an alien, for the purpose of their removal from Australia, did not infringe ... the Constitution because the authority, limited to that purpose, was neither punitive in character nor part of the judicial power of the Commonwealth,” Chief Justice Robert French wrote, according to the Australian, with other justices.

The lawyers of the Bangladeshi woman had said that her imprisonment in Nauru was “funded, authorized, procured and effectively controlled” by the Australian government, without the constitutional power to do so, Al Jazeera reported. The lawyers also said, according to Sydney Morning Herald, that the Commonwealth lacked the authority to enter into a memorandum of understanding with Nauru and that there was no authority to use the funds for that regime.

Daniel Webb, the director of legal advocacy at the Human Rights Law Center and one of the lawyers who brought in the case, said, according to the Guardian, that the government should not return the “very vulnerable” group of asylum-seekers to Nauru. Webb said: “The legality is one thing; the morality is another,” adding: “It is fundamentally wrong to condemn these people to a life in limbo on a tiny island. The stroke of a pen is all that it would take our prime minister or our immigration minister [Peter Dutton] to do the decent thing and let these families stay.”

Dutton had reportedly said before the ruling that he would take a “compassionate” approach toward the issue and not send children “into harm’s way,” as reports had said that a five-year-old boy was sexually assaulted on the island. He had said, according to the Australian: “We’ll have a look at the individual cases. We’ve been very clear that we want to provide medical support to some families that are in need.”

Webb had also reportedly said that the country’s prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, was the only one to approach now.

However, Turnbull, facing calls to prevent the asylum-seekers from being sent back to Nauru, after the ruling said, according to Al Jazeera, that the court’s decision was “significant.”

He said, according to the Guardian: “Nobody should ever doubt the resolve of this government to keep our borders secure, to prevent the people-smuggling racquet, to break their business model and keep lives safe, to prevent drownings at sea and to protect vulnerable people from being exploited by ruthless criminal gangs,” adding: “Our commitment today is simply this: the people smugglers will not prevail over our sovereignty. Our borders are secure. The line has to be drawn somewhere and it is drawn at our border.”

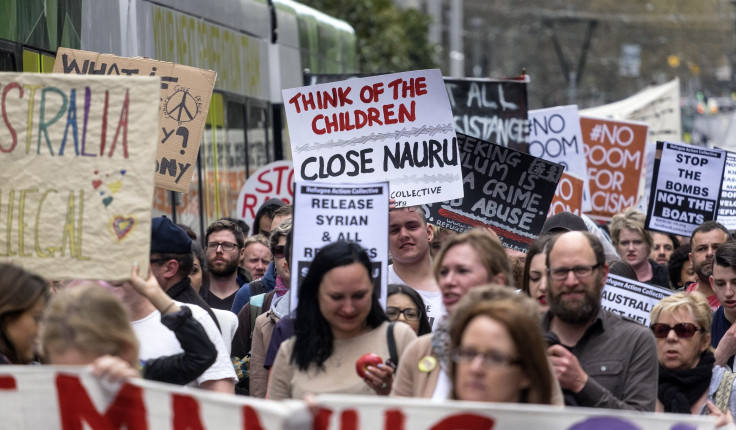

The court’s decision was slammed by human rights activists who said that the conditions at the island, to which journalists and rights groups are usually refused a visa, were not convenient.

The United Nations Children's Fund condemned the decision and said, according to Al Jazeera, that the ruling “has no bearing on Australia’s moral responsibility or its obligations to protect the rights of children in accordance with international human rights law,” adding: “It is unreasonable for the Australian government to shift responsibility for this group of children and families with complex needs to a developing state in the region.”

The organization also said: “UNICEF Australia is also concerned for children who were born in Australia but who may be transferred to Nauru on the basis of a decision by the minister for immigration and border protection,” adding: “The current offshore immigration network is a system in crisis and is creating crisis for affected children and families.”

Amnesty International’s Australia refugee coordinator, Graham Thom, said, according to the Guardian: “Despite the high court decision in this case, Amnesty International calls on Prime Minister Turnbull to do the right thing and permanently close the centre on Nauru and relocate the asylum-seekers held there into our community,” adding: “The Nauru processing centre puts vulnerable people at risk and operates with an unacceptable lack of transparency.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.