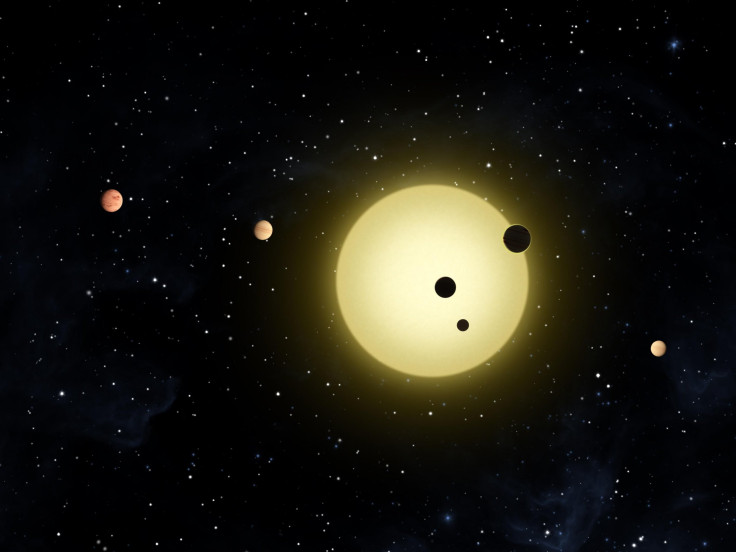

Bizzare Tilted Solar System Discovered By NASA’s Kepler Spacecraft

As scientists continue to analyze the year’s data gathered by NASA’s now defunct Kepler Space Telescope, they continue to uncover new information about the planets and stars outside of the solar system.

Reported in this week’s issue of the journal Science, their latest discovery is a first of its kind -- a “titled” multiplanet star system that is out of alignment with its host star. Named Kepler-56, the host star has been monitored closely by NASA for the last few years. Located about 3,000 light years from Earth and measuring close to four times as wide as our sun, Kepler-56 is just one of 150,000 stars that NASA monitored with the telescope, reports NBC News.

Tilted orbits have previously been found in planetary systems that include a large planet that orbits close to its host star -- known as "hot Jupiters." But this is the first time these tilts have been seen in multi-planet system that doesn't contain a giant "hot Jupiter."

Kepler can identify planets in distant star systems by monitoring the variation in brightness of light that comes from the stars as the world’s pass over them in an event called transiting. The craft discovered two planets large enough to be considered gas giants orbiting Kepler-56. These orbits were traced to last the equivalent of 10.5 and 21 Earth days. And using what is known as asteroseismology -- which is studying the structure of the actual star -- Kepler uncovered that the plane of Kepler-56’s equator tilts 45 degrees in relation to the plane of the planets’ orbit.

"It was a big suprise," lead author Daniel Huber of NASA’s Ames Research Center told Nature.

By using the 10-metre Keck I telescope -- which is located on the Mauna Kea volcano in Hawaii -- they measured the velocity of Kepler-56. They then used this measurement to determine what was causing the tilt of the planets, Nature reports. This work led the team to a third, distant body that could be either another star or planet. The body doesn’t transit Kepler-56. But its gravitational pull is strong enough to pull the Kepler-56 star and tilt the orbit of its planets.

The tilt of the planets doesn’t affect the alignment of their orbit with each other, though. This is due to the fact that one of the planets takes twice the time to circle the star than the other. As a result, they push each other through their gravity, keeping their orbits in alignment despite their massive tilt in relation to Kepler-56’s equator.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.