Can China's Land Reform Succeed Amid Land Grabs And Social Unrest?

Hopes about land reform are running high in China, where the unique land system is seen as a bottleneck for urbanization and has contributed to the surge in home prices. On average, housing prices in 100 Chinese cities tracked by China Real Estate Index System rose 8.6 percent in August from a year earlier, with Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen seeing increases in the 20 percent range.

The Chinese government is widely expected to issue details about the potential land reform around the time the third plenary session of the 18th Central Committee takes place in November.

Considered as an important part of China’s urbanization drive, land reform could increase urban home supply and help cool the red-hot real estate market. But in most cases, the very process that promises shared prosperity simply means local government forcing farmers into buildings while grabbing their land. The scheme aims at making more non-farming land in rural areas tradable and thus available for building apartment blocks, shopping malls, roads and airports. Non-farming land includes land on which farmers’ own houses stand.

Residential buildings as well as factories, stores and the like have to be built on land for construction, which could be further divided into urban and rural sections.

“Only new homes built on urban land for construction could be sold in the property market. And rural land for construction is not allowed to be sold in the market by farmers unless it is procured by the government and converted into urban land for construction,” according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch economists Zhi Xiaojia and Lu Ting.

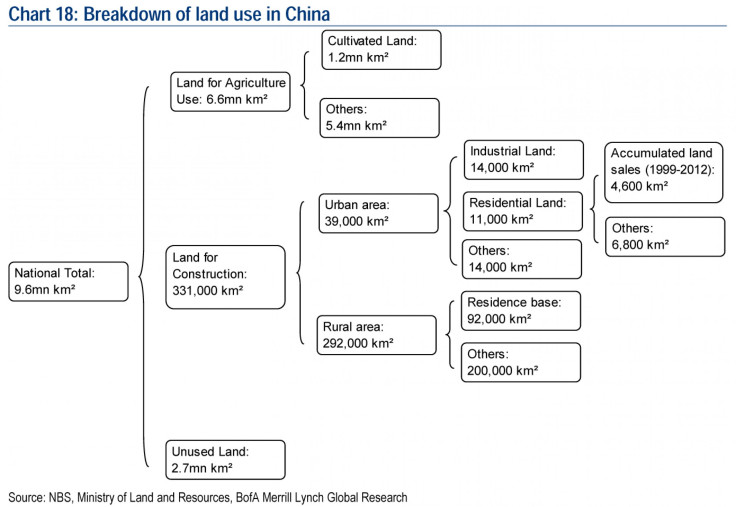

According to government plans, China’s total area of 9.6 million square kilometers (3.7 million square miles) could be divided into three parts: (1) Land for agricultural use: 6.6 million square kilometers; (2) land for construction: 331,000 square kilometers; and (3) unused land: 2.7 million square kilometers.

Urban land for construction (39,000 square kilometers) could be divided into land for industrial use (14,000 square kilometers), residential land (11,000 square kilometers) and others (for instance: public buildings, transportation, 14,000 square kilometers). Residential land is used for property development.

Rural land for construction (292,000 square kilometers) could also be divided into two parts. Of this, 92,000 square kilometers is used for residential land for farmers and is also called a residence base. The remaining 200,000 square kilometers is used for public buildings and rural enterprises.

The economists wrote: Clearly, an imbalance exists between urban and rural areas with regard to residential land. While 53 percent of the Chinese population, or 712 million, are now living in urban areas, they occupy only 11 percent of the residential land in China, or 11,000 square kilometers. On the other hand, the vast 92,000 square kilometers rural residential land is not properly utilized, with a significant portion idled as young rural labor has moved to cities for better jobs.

“China currently has 250 million migrant workers, and additional 200 million people will move from rural to urban areas, as we expect China's urbanization to reach 65 percent in the next 10 years,” Zhi and Lu said, adding that China needs to increase urban residential land supply to meet the sustained real demand for urban homes. Despite surging home prices in the past several years, annual land sales to developers have been limited at around 400 square kilometers.

What Could Go Wrong

“The central leadership is concerned that the transfer of collective construction land could lead to a large number of farmers losing their land [and this could] become a factor of social instability. This is why the State Council has always refrained from taking a clear stand on the issue,” China Real Estate News quoted an unnamed source as saying.

Chinese farmers don’t actually own their land; they only have the right to use it. All land in China is still owned by the government. As Beijing begins reform designed to give farmers ownership of that land, the effort is running into the cold reality that the economic system allows local government and developers to make vast profits from one-sided land deals with farmers who have little ability to resist. Moreover, development boosts local tax revenue and output -- both measures by which government officials are judged for promotion.

One recent estimate by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences researcher Yuhui Liu puts local government debt at an astonishing level of 20 trillion yuan. And land sales revenue is an important source of income for local governments, amounting to a net 1.4 trillion yuan ($230 billion) in 2012, or around 11 percent of local governments’ total income, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

In one survey by Landesa in 2011 (the latest available), 43 percent of Chinese villagers said government officials had taken or tried to take their land. That is up from 29 percent in a 2008 survey. The same survey found that on average, compensation governments paid to farmers was just 2 percent of the land's market value.

Approximately 4 million rural people’s land is taken by government every year and conflict over land accounted for 65 percent of the 187,000 mass conflicts in China in 2010, according to the researchers.

When farmers are relocated or "urbanized," only a bit more than twenty percent gained an urban hukou or registration; 13.9 percent received urban social security coverage; 9.4 percent received medical insurance; and only 21.4 percent had access to schools for their children.

Violent clashes between officials and villagers have recently resulted in the death of a four-year-old girl, Xiaorou Hong, who was hit by a bulldozer after her family resisted a land grab. Haifeng Xu, whose home was razed three years ago, told Reuters the story of how her family members had been kidnapped on 18 separate occasions after she went to Beijing to complain about the city and county governments that ordered the demolition. According to Xu, her family members were taken to a hotel-turned-illegal jail in the eastern city of Wuxi with black bags thrust over their heads and locked for weeks in a tiny, windowless room.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.