China's Exclusive Social Network For Business Elite, 'Zhenghe Island,' Bans Political Talk

There was a time when Facebook was an exclusive social media network, made specifically for Ivy League college students looking to connect. Since then, Facebook has opened up its site to anyone with an Internet connection.

Now some in China’s elite are reverting to exclusivity, signing up for an invitation-only social network for the nation’s wealthy and powerful. Unlike with Facebook, however, membership to the online community doesn’t come easy, or cheap. Furthermore, restrictions on content discussed among group members both online and in person reveal China’s politics-fearing business culture.

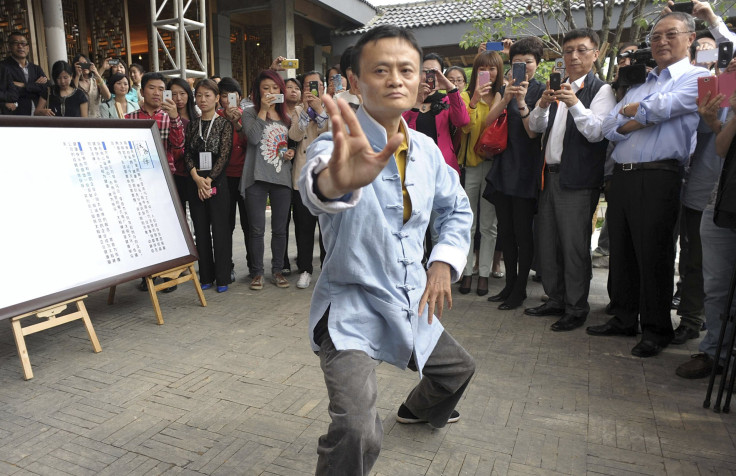

In order to qualify for membership, one is required to pay an annual fee of 30,000 yuan, roughly $4,890, and must also be with a company that has annual revenues of 50 million yuan or more. According to a report by the South China Morning Post of Hong Kong, members of the exclusive social network, Zhenghe Island, include more than 2,000 of China’s biggest movers and shakers, including Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba (HKG:1688) and China Vanke Co. (SHE:200002) Chairman Wang Shi.

Until recently, Zhenghe Island remained under the radar as a casual place where important business leaders were able to exchange personal views in confidentiality. The private network was revealed after a heated exchange at a Zhenghe members-only gathering between the opinionated fund manager Wang Ying and Lenovo Group Ltd. (HKG:0992) founder Liu Chuanzhi, after Liu said members should “stay out of politics and talk only business.” Liu’s statement was echoed by Zhenghe Island, adopting that as part of the site’s official position on politics.

Later, Wang publicly posted about the incident, saying she was withdrawing her membership because she believed politics and business in China are too intertwined to ignore. “I am not one of the entrepreneurs who do not talk politics, and I do not believe China’s business owners will survive if they kneel,” she wrote in her statement.

In China business and politics are increasingly hard to separate, particularly when the nation’s biggest companies are state-owned. Wang said the initial draw of Zhenghe was that she was able to connect with people like her with similar interests, extending beyond just business. Users on Zhenghe even began fostering social friendships, maintaining conversations on WeChat, China’s most popular mobile chatting service. Last November, Wang started a WeChat discussion on Robert’s Rules of Order, a book on parliamentary rules used widely in the United States. The aim of the group was to help each other establish more democratic management styles and frameworks at their respective companies, using the book as a frame of reference.

Wang told the SCMP that Liu’s decision denouncing political conversation and Zhenghe’s subsequent support of Liu’s comments is contributing to a common practice of businesses bowing to censorship of political talk. “The reason I criticize Liu is because, at this moment, he encouraged and fueled a fear of politics that is spreading among Chinese business sectors,” Wang said. “I’ve been devoted to public interest-related projects for 13 years, but I’ve never encountered danger. I believe that the government and political party who cannot be criticized is in most need of criticism. If I’m in danger because I criticize, I think the state is in bigger risk than I am.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.