Fed Meeting Preview: QE3 Has Arrived

If it seems like it's been months and months since market-watchers started hyping the possibility that the U.S. Federal Reserve would engage in a third round of liquidity-enhancing asset purchases -- so-called "Q3" -- that's because it has been.

According to global news database Factiva, the very first mention of "QE3" as a financial term was on Sept. 28, 2010, when former derivatives trader Todd Harrison wrote on the financial education site Minyanville.com that "there ain't gonna be no QE3."

At that point, the Fed had not even officially revealed QE2, only strongly hinting that it would pursue such a policy. Yet Harrison was certain that was about as much as the central bank could stomach.

"Think Rocky Balboa at the end of the first movie; there ain't gonna be no rematch," Harrison noted, adding that QE2 was "the next to last bullet (and you know where the last one is pointed)."

One year, 11 months and 14 days later, having gone through a sovereign credit downgrade, the near-collapse of the European financial system, and facing an anemic recovery that has only marginally helped heal the carnage in the labor and housing markets, the vast majority of financial pundits, including Harrison, believe QE3 is "pretty much a given."

The first question is not if, but when

Markets seem to be indicating that QE3 could come as soon as the meeting of the Federal Reserve's Open Market Committee this Thursday. A report by Citigroup cited by Bloomberg News Tuesday notes "a gauge of indicators of market expectations for additional central bank stimulus rose to a record 99 percent in August."

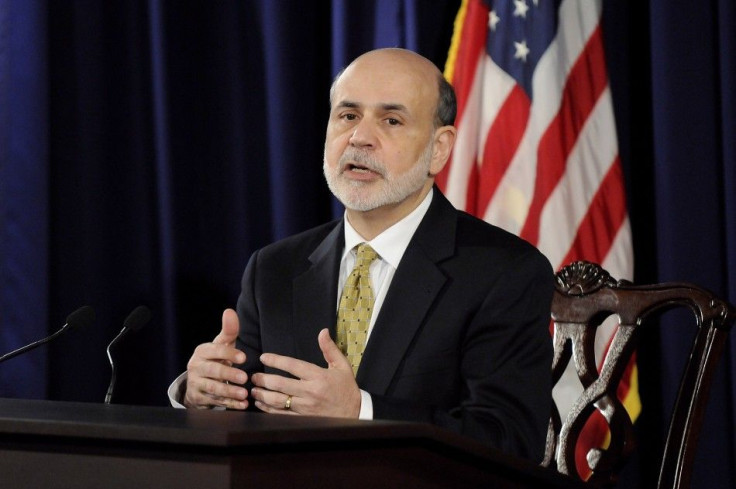

Referencing the annual summit that took place in Jackson Hole, Wyo., late last month, Neela Gollapudi, a New York-based strategist at Citigroup, told Bloomberg that "the market thinks that at Jackson Hole, [U.S. Fed Chairman Ben] Bernanke was saying conditions are pretty bad."

Indeed, many analysts have been convinced that Bernanke signaled QE3 when he noted in his speech to open the summit that there was still "grave concern" about the pace of the labor market recovery. Economists at Goldman Sachs and BNP Paribas are both expecting the announcement of an open-ended bond buying plan this week. UBS sees "a six-month program of at least $500 billion, primarily focused on Treasury securities."

Michael Gapen, an economist at Barclays, suggests the Fed will set aside "around $50 billion per month," with the funds "to be split evenly between long-term Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities."

Some of these experts were convinced following the Fed's last appearance at Jackson Hole, and have been further moved in their predictions by a dramatically underwhelming employment report out last Friday, which found some 96,000 jobs -- considerably less than the amount needed to keep up with population growth -- had been created in August.

The few dissenters from what is the Wall Street consensus, including Japanese financial services firm Nomura, point out that, apart from the uninspired job creation numbers, the economy is slowly getting better, something that will give the Fed more breathing room to put off a dramatic action like open-ended bond-buying for later this year, in case another political or economic crisis absolutely necessitates the move.

There are also those that have pointed out a highly influential paper presented at Jackson Hole by Michael Woodford, an economist with the Graduate School of Business at Columbia University, could influence the Fed to look at methods beyond asset purchases, perhaps choosing to issue robust forward guidance on inflation levels it is likely to tolerate in the long term instead.

However, most economists believe that this time, the writing is on the wall.

The second question, then, is how effective the Fed's action will be.

Here, economists differ more widely.

At JPMorgan, strategists are assuming QE3 will come soon, though not necessarily this week, but believe its effect will be limited, noting they are "bearish on duration" of a QE3-inspired rally as "poor technicals, rich valuations, and the improvement in the broader set of economic data argue for higher rates"

By comparison, Bill McBride, a highly regarded economics expert who runs influential finance blog Calculated Risk, recently wrote that QE3 will in some regards be more effective this time than in previous iterations, as the "transmission mechanism" meant to stimulate the economy through purchases of mortgage -backed securities is considerably more robust at the moment than in previous months.

The final question is whether the action will have any negative effects.

"The world drowning in liquidity," Michael Cembalest, global head of investment strategy at JPMorgan, wrote in a note to clients this week, noting the attitude by the world's politicians has been to "look through all the economic weakness and expect that continued monetary stimulus will eventually bear fruit."

"The world's Central Banks have made it clear that inflating their way out is preferable to the alternatives, an environment that is conducive to risky assets that are priced very cheaply, until and unless they lose control of inflation," Cembalest added.

That fear tha inflation expectations will become "unmoored," as Chairman Bernanke himself has cautioned in the past, is the main drawback to any stimulus. But because that fear of inflation has created aggresive reactions in the political sphere, the independence the central bank needs to operate is also a possible casualty of much further easing by the Fed.

"With [the] US election extremely close any move by the Fed will be viewed through highly partisan prism and may create more harm than good as it creates a swirl of controversy. With Fed officials already under fire from the right side of the electorate the outcry will no doubt be fierce if the Fed proposes a major shift in monetary policy so close ahead of the election," Boris Schlossberg, managing director of foreign exchange strategy at BK Asset Management, wrote in a note to clients this week, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Losing that independence to act, while a distant risk, is still a possibility acknowledged by Fed economists. In such a case, the bank would really be down to its last bullet.

(And you know where the last one is pointed.)

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.