The Fight For Single-Payer Health Care Intensifies In California

This story is being co-published with Capital & Main as part of a series on California Game Changers: Nine Big Ideas That Could Transform the State and Nation.

This autumn could prove decisive for the question of whether California may again be on track to enjoy what the rest of the industrialized world has long taken for granted — universal, government-provided health insurance, a dream that dates back to the Truman administration. Although the Affordable Care Act was spectacularly successful in lowering the state’s uninsured rate from 17.2 percent to 7.3 percent, according to the latest census data, that still represents a roughly 2.8 million-person gap in California’s health coverage. And health care advocates argue that too many with private insurance continue to fall victim to the catastrophic failure of a for-profit health care model plagued by extraordinary complexity and costly administrative inefficiency.

Paul Y. Song, an oncologist on the board of Physicians for a National Health Program, told Capital & Main that with or without a GOP repeal, the withering Republican assault on the ACA has exacerbated the financial hardships of many recently insured Californians struggling simply to maintain their coverage. Song is also the co-chair of Healthy California, a campaign that supports passage of state Senate Bill 562, a single-payer measure that stalled in Sacramento when Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) tabled it in June.

“The number of people reporting difficulty paying monthly premiums has gone up to nearly 37 percent,” Song noted. “California ranks third from the bottom in terms of narrow networks, which means that if you have an emergency and you need to see a doctor, chances are the majority of the time a doctor will not be in your network and you'll get charged all of these out-of-network prices. … Anthem announced earlier this year that they were going to raise rates. They were either going to pull out of the exchange in California in certain areas, or raise rates 35 percent. People are now waking up and saying enough is enough.”

California Democratic leaders, state labor and health care advocates have never seemed more galvanized around the principle that quality health care is a fundamental right for all Californians. The divisive question of how to best achieve it is set to be taken up in a series of hearings over the next several months by the Assembly Select Committee on Health Care Delivery Systems and Universal Coverage, announced in March by Speaker Rendon. The hearings begin October 23-24.

For both single-payer advocates and opponents in Sacramento, as well as Washington, the debate is ultimately about far more than health care. Battle lines have formed around bedrock questions of who we want to be as a people: Should suspicion of “big government” take priority over the broader welfare of the population? Will the cruelties of the unfettered marketplace be tolerated in the name of American individualism?

In the meantime, experiencing the harrowing contradictions of California’s health care system continues to be the day-to-day reality of front-line caregivers. Melissa Johnson-Camacho, an oncology nurse in Davis who has also spoken in favor of single payer before the U.S. Senate, told Capital & Main how she remains haunted by the experience of caring for a young woman riddled with metastasized cancer.

Because the girl’s cancer had spread to her lungs, she was at risk of drowning in her own pleural fluid and her life now hinged on a daily supply of pharmaceutical-grade catheter bags to safely drain the lungs.

“Her mom was with her as a caregiver, so she starts telling me about the drains and that she would change them more often, but they couldn't afford it,” Johnson-Camacho said. “It was unspoken, but I know her mom was [thinking], ‘How much supplies am I going to need when I know she's not going to be here much longer?’”

Facing renewal of the girl’s crippling annual deductible of her private insurance plan, the family was trying to stockpile her supply of bags, which can list for around $5,000 per day, by exceeding their recommended capacity.

“Nobody should ever have to make a decision like this,” said Johnson-Camacho. “Especially when you're paying into a system. It was just angering. It was sobering. It was tragic. That was one of many times that I thought, ‘We've got to change this.’”

That’s why, Johnson-Camacho offered, she’ll be joining in the Healthy California campaign’s Medicare-for-All October Weekend of Action, in which she and fellow activists hope to canvass all 80 Assembly districts across the state to urge voters to flood Sacramento with letters demanding action on SB 562.

“There's a lot of different forces out there that don't want to see this bill move forward,” said Don Nielsen, chief lobbyist for the California Nurses Association (CNA), which is a sponsor of the bill (and a financial supporter of the Capital&Main website). “Select committees can't do anything other than take testimony. They can't move our bill. And we're concerned that the process is more about slowing down the momentum of the incredible public support for Medicare for All, single payer and SB 562. People know that the system is broken. They want to see it fixed.”

Rendon’s press spokesperson, Kevin Liao, countered that far from being a stalling maneuver, the Select Committee was designed to allow a broader discussion on getting to health care for all, and that nothing was stopping SB 562’s authors from redressing the bill’s “potentially fatal flaws”: “Speaker Rendon laid out a clear path for SB 562 — the Senate can send to the Assembly workable legislation that includes financing, delivery of care and cost control.”

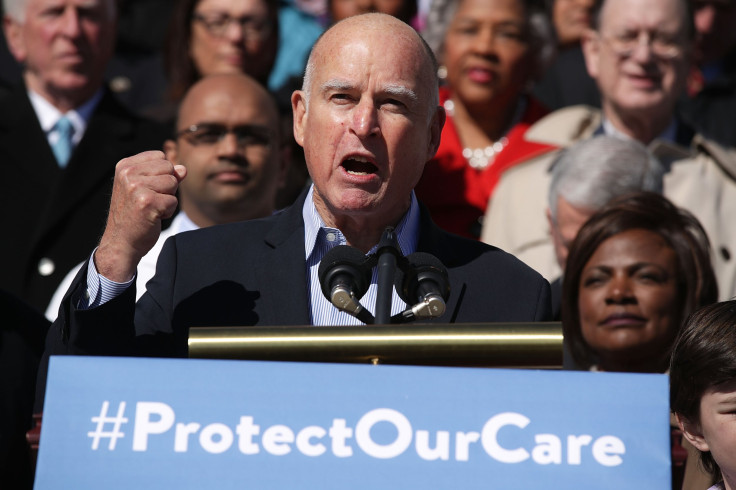

But Healthy California’s timetable to iron out those critical details and then get the bill through committee and floor votes, and finally to the desk of a less-than-enthusiastic Governor Jerry Brown by the end of the 2018 session is ambitious, reflected Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California. The veteran consumer health advocate, who has lobbied on behalf of universal, single-payer health care bills and initiatives dating back to Proposition 186’s Medicare for All-type ballot initiative in 1994, said that the coalition has its work cut out.

“A health system can be very complex and confusing,” said Wright. “The same obstacles that prevented us in previous attempts still remain, and in fact loom even larger. Vermont had an Obama administration that was willing to work with them to figure out the various financing and other issues. For the next three, four years, we'll have a Trump administration in that same role, which will probably not be helpful."

The executive director of the California School Employees Association, Dave Low, concurred. “We need federal waivers to a California single-payer bill,” he explained. “We know that there is a heavy lift. Just the poll that recently came out showing that we don't even have a majority support on the single-payer issue shows that we have work to do, and we want to do that work.” (Disclosure: CSEA is a financial supporter of Capital&Main website.)

Trump aside, it turns out that there’s little economic reason why California couldn’t go it alone with single payer, and a host of reasons why it should. A CNA-commissioned study found that by lowering administrative costs, controlling the prices of pharmaceuticals and fees for physicians and hospitals, reducing unnecessary treatments and expanding preventive care, Healthy California’s single payer could deliver coverage to every California resident for about $331 billion, or 10 percent less than the $370 billion the state currently spends.

California has size in its favor. The state’s $2.4 trillion annual gross domestic product ranks neck-and-neck with France’s GDP, and California's population of 39 million puts it above Canada’s. Yet at $7,549 per person, the state spends considerably more on health care with its market-based system than both countries — $5,292 for Canada; $4,959 for France — do with their universal single-payer systems, while getting substantially less bang for its buck. According to the Commonwealth Fund, while California ranks 14th in the nation on health care access, efficiency and equity, the U.S. consistently comes in last or near last on those measures relative to its industrialized peers. In terms of infant mortality, the state’s 4.7 deaths per 1,000 births places it just behind Cuba (4.51), Canada (4.53) and Greece (4.58), and 40 places behind Japan.

“What I see daily on my job is that many children who have serious illnesses, their families have delayed care because they couldn’t afford access to care early on,” observed Martha Kuhl, a pediatrics oncology nurse at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital in Oakland, who has been in the field for 36 years. “Even when they had insurance, they couldn't afford the point-of-care copays. They were having trouble with deductibles, so they would delay care until it felt absolutely necessary. In a child with cancer, that can seriously affect the outcome and the treatment protocol, and actually whether or not your child survives.”

Although Dickensian accounts of parents being forced to choose between losing their home or losing a sick child are common, Kuhl attributes much of the system failure to the nightmarish administrative labyrinth imposed by the private insurance marketplace.

“It's tragic,” Johnson-Camacho said. “I went to school to help people, not to follow up with the pharmacy to make sure my patients’ meds are going to be covered.”

For the private insurance and pharmaceutical industries, the single-payer fight in California, which has historically been a national political bellwether, represents a struggle for their very survival. Groups opposing SB 562 have given more than $1.5 million to the Assembly’s Democratic caucus since the 2012 election cycle. In just the last three election cycles, International Business Times recently reported, Assembly Democrats have received more than $2.7 million in pharmaceutical and health insurance industries contributions.

“I've been a nurse for a long time, and I have watched the system change,” Kuhl reflected ruefully. “There were always people who didn't have health insurance or couldn't afford the care that they needed, but it felt like a nicer system in some way. These days, business is the first priority. Insurance companies’ primary goal is to make money, and they do that by denying care.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.