Ford Motor Company Aims For Water-Free Plants As Droughts, Pollution Threaten Corporate Bottom Lines

Ford Motor Co. is steadily tightening the taps at its car-producing plants around the globe. The U.S. auto giant has more than halved its water use over the last decade through fixes as simple as repairing leaky pipes to complex upgrades in its painting and metal-cutting systems. The Detroit automaker says its ultimate aim is to completely eliminate water from its production. And while water-free assembly lines are still years away, Ford says it’s chasing the lofty goal to spare the company future pain as global supplies reach critical lows and regulators clamp down on water permits.

“We want to find ways that totally reduce our footprint, that -- to the extent we can -- do not use water,” said Andy Hobbs, who directs Ford’s environmental quality office in Detroit. “We don’t know how to get to a full zero yet, but we’re getting close.”

Ford is among the rare handful of global companies that see an economic incentive in drastically curbing water use from operations and supply chains. They’re doing so as water crises -- from droughts and depleted aquifers to polluted drinking water -- increasingly threaten to undercut global economic growth. The World Economic Forum this year ranked water issues as the greatest risk to economies and people in the next decade. Yet the majority of the world’s businesses aren’t preparing for a water-scarce future. As populations rise, demand for energy grows and climate change accelerates, those firms might find themselves scrambling for the remaining drops of clean water, the Swiss organization said.

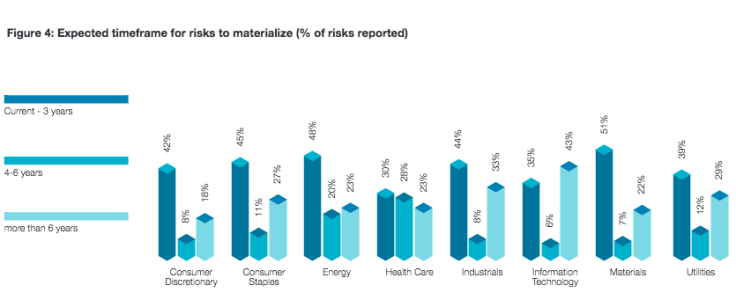

Major businesses say they’re already feeling the pressures of a water-constrained world, both to their bottom lines and from sustainability-focused shareholders. In a survey released Thursday, nearly two-thirds of companies said they expected water concerns to affect their operations or financials in the coming years, according to CDP, a climate advocacy group in London. About one-fourth of firms said they’ve recently experienced “detrimental” water-related impacts, including lack of adequate supplies or regulatory curbs on operations. CDP surveyed 405 publicly listed companies for its annual Global Water Report, although hundreds more businesses did not respond to survey requests.

“We’re seeing more strongly than ever that … water security is a business imperative,” said Marcus Norton, chief partnerships officer for CDP and its former water programs director. “We want companies to be changing their behaviors and becoming part of the solution.”

Hobbs said Ford began working in earnest to slash water use around 2000, when the Big Three automaker created its environmental quality office and adopted a broader corporate sustainability agenda. “When we looked at the company globally, 20 to 30 percent of our facilities were in extremely water-stressed areas,” including in northern Mexico, southern Spain and in parts of the U.K., he said.

Ford’s first water-related fixes were relatively low-hanging fruit: Seal dripping faucets and leaking fire hydrants, upgrade building equipment to water-conserving models. Ford also recycled and reused more water where it could in place of potable water.

The more dramatic changes arrived on Ford’s factory floors, particularly during the painting process. The conventional way to paint vehicles requires dousing cars with water after each coat, resulting in a thick sludge that has to be treated. But with the “3-wet” system, Ford immediately applies the primer, base coat and clear top coat while they’re still wet, reducing the need to hose down vehicles and cutting energy costs. General Motors and other automakers are adopting similar approaches at some of their plants.

Ford is also cutting water use from the manufacturing of metal products, such as engines, transmissions and components. Typically, metal-cutting tools are frequently flooded with water and fluids to keep tools from overheating or jamming up. With “dry-machining” -- also called Minimum Quantity Lubrication -- mechanics apply tiny amounts of water and oil to precise points on the tools. Ford estimates the dry approach can save more than 280,000 gallons of water per year on a typical production line.

The U.S. auto giant incorporated all these approaches when expanding its assembly plant in Hermosillo, Mexico, where it makes the Fusion sedan and Lincoln MKZ luxury car. Ford boosted production volume by 40 percent without raising its water use, Hobbs said. The company has since replicated this approach at its plants in India and China.

Overall, Ford says it has cut total total water consumption by 62 percent from 2000 to 2014, avoiding roughly 10 billion gallons of water. Hobbs acknowledged the higher costs of upgrading equipment and repairing facilities to be more water efficient. But he said Ford ultimately would’ve spent more money to use all that H20, given that procuring and treating water is become more expensive globally.

“When we started down this path, water was inexpensive,” he said. “But because we reduced by that much, our costs are actually flat, because the cost of water has gone up so high.”

Ford reported $135.8 billion in automotive revenues in 2014, with U.S. auto sales totaling nearly 2.5 million that year.

CDP, the environmental organization, listed Ford as one of the eight “A List” companies for water conservation in its Thursday report. The other water-saving corporations include Japan’s Toyota Motor Corp., two South African mining companies -- Harmony Gold Mining Co. and Kumbra Iron Ore -- as well as Colgate Palmolive Company, the U.S. consumer products manufacturer.

Still, the CDP survey suggested the A-list companies were the exception, not the norm, when it comes to corporate water sustainability. More than 60 percent of the public companies that CDP approached for the survey, or nearly 700 companies, ignored or declined the request, which CDP typically takes to be a sign that executives aren’t interested in the topic. “That’s clearly a significant concern,” said Norton, the CDP executive. “There’s a real gap between the leaders and laggards.”

The oil and gas sector -- one of the world’s most water-intensive industries -- had the lowest turnout in the CDP survey, with only a 22 percent response rate. But of the firms that did respond, 85 percent said their operations are exposed to “substantive” water risks, including the risk of oil spills, limited freshwater supplies and even reputational risks associated with guzzling water in water-stressed regions.

A separate report in May found a similarly lackluster showing from 37 major U.S. and global food companies. Ceres, a coalition of environmentally focused investors, found that while most companies acknowledge the risks they face from a lack of water, only a handful are actively working to slash water consumption and protect the rivers and watersheds that sustain their fields and livestock.

Yet food companies are seeing their profits squeezed and investments stymied because of water-related challenges. Agribusiness giant Cargill Inc. closed a beef-harvest facility in Milwaukee in 2014 and is shuttering a corn-milling feed facility in Tennessee due to drought-related declines in the U.S. beef-cattle herd. This spring, Coca-Cola Co. scrapped plans for an $81 million bottling plant in southern India because of opposition by local farmers, who feared the facility would strain groundwater supplies.

In CDP’s latest water survey, companies reported more than $2.5 billion in water-related impacts in the last year. The figure doesn’t include proactive expenses, like the $3 billion that BHP Billiton Ltd. and Rio Tinto Plc are planning to spend for a seawater desalination plant at one of Chile’s largest copper mines in the Atacama desert. “Something that’s often missed in this space is that the true value of water to a business comes in terms of its license to operate, brand value and business resilience,” Norton said. “Those things are very difficult to quantify.”

Back in Detroit, Hobbs said Ford is still pushing to find the technologies and techniques that will help it eliminate water from production lines. Their mission is growing more urgent, he said, pointing to the brutal four-year drought in California and significant supply constraints in China and India. “The environments in which we operate are changing,” he added. “The water-stressed areas are really becoming more water-stressed.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.