Haiti's Colonial Debt Burden Sparks Debate -- But Official Silence

A newspaper expose has reignited debate over the ongoing legacy of debts that Haiti was forced to pay to former colonial ruler France in the 19th century -- but the country's elites are surprisingly keen to bury the issue.

After months of poring over archives, The New York Times estimated that debt payments starting in 1825 cost poverty-stricken Haiti between $21 billion and $115 billion -- or as much as eight times its GDP in 2020.

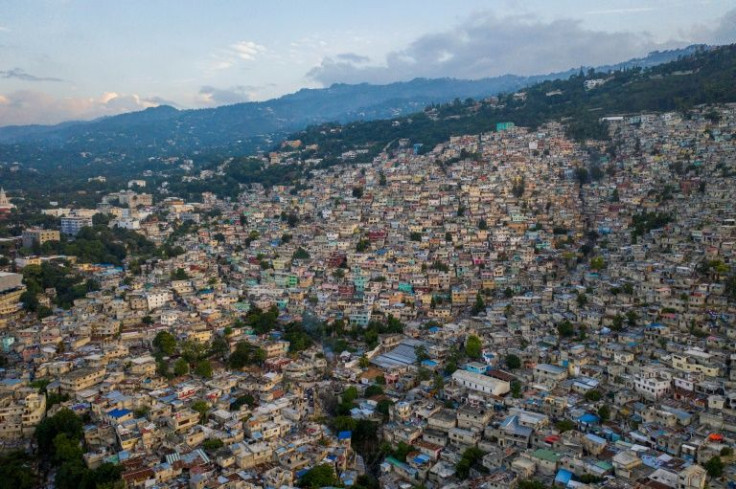

In Haiti, the figures have added fresh fuel to a fierce debate that stands in stark contrast to the silence from authorities in the capital Port-au-Prince and the political opposition.

"Haitian politicians have the unfortunate tendency to work only in the present," Haitian historian Pierre Buteau told AFP.

"Men and women in politics are only interested in the fight to gain power."

Haitian leaders' reluctance to speak out about the country having to pay France back after it gained independence also partly stems from a pattern of Western intervention in Haiti in the recent past.

In 2003, then president Jean-Bertrand Aristide made the debt issue a rallying cry, and estimated that France took in more than $21 billion from Haiti.

But, facing a military insurrection and a popular revolt alleging human rights violations, Aristide was overthrown in 2004, under strong pressure from the United States, France and Canada.

Questioned nearly 20 years later by The New York Times, the French ambassador at the time, Thierry Burkard, admitted that Aristide's removal was "probably a bit about" his call for reparations from France.

When it declared independence in 1804, Haiti became the world's first black-ruled republic and an outcast in an era dominated by countries that engaged in slavery.

It had to pay France for the freedom of its citizens who had been slaves -- and was pitched into impossibly heavy repayments, rapid defaults and toxic loans from France.

"The way in which over the course of 150 years Haiti had to pay France for having wanted to be free... compromised Haiti's very insertion on the international scene," French economist Thomas Piketty said in 2019 as he promoted his book "Capital and Ideology" in which he tackled how Haiti incurred colossal debt.

The payments to France not only denied Haiti critically needed resources -- they also helped build up France itself.

The Times showed that in the late 19th century a bank called CIC repatriated money from the new Haitian national bank that came from loans that were supposed to help Haiti pay off its debt.

The money in turn helped Parisian banks to finance the construction of the Eiffel Tower.

The current parent company of CIC, Credit Mutuel, released a statement Monday in response to the Times investigation.

"As it is important to clarify all the components of the history of colonization, including in the 1870s, the bank will finance independent university research to shine a light on this past," Credit Mutuel said.

Reaction to the New York Times investigation was mixed, with some experts and academics accusing it of downplaying Aristide's crimes to emphasize the narrative that he was ousted for seeking for reparations from France.

US former diplomat Patrick Gaspard, whose parents were from Haiti, said it was "an inexplicable whitewashing on the internal violence and corruption in the Aristide era that can't just be explained away by pointing to France and the US."

In its articles, the Times also showed that Haiti's gold reserves were raided by American soldiers at the start of the 20th century.

"In the drowsy hours of a December afternoon, eight American Marines strolled into the headquarters of Haiti's national bank and walked out with $500,000 in gold, packed in wooden boxes," the Times wrote.

This was prior to a full scale US invasion of Haiti by the US army, which occupied the country from 1915 to 1934.

The US retained direct control over Haiti's finances for more than a decade after US troops went back home.

Haiti today is mired by grinding poverty, murderous gangs who control large parts of the capital, and political chaos that included the assassination of the president last year.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.