January FOMC Meeting Preview: Fed To Taper Again At Ben Bernanke’s Last Meeting

The U.S. Federal Reserve is likely to meet investor expectations by cutting asset purchases again by $10 billion a month at the end of the Jan. 28-29 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, which is the last meeting for outgoing Chairman Ben Bernanke.

This will bring the monthly pace of asset purchases to $65 billion for February, consisting of $35 billion of Treasurys and $30 billion of mortgage-backed securities.

Turmoil in emerging markets has fueled some speculation that the Fed will hold back from announcing a further reduction in its monthly asset purchases Wednesday. But economists believe the Fed will be keen to give the impression of continuity and stability in its policymaking.

“Deviating from its widely-anticipated course so soon, especially when the U.S. economic outlook has brightened, would probably put its credibility at risk,” Capital Economics' Jessica Hinds wrote in a note.

Admittedly, December’s payrolls numbers were poor, but the Fed will disregard one month’s data that were probably distorted by the severe winter weather. “The FOMC will likely be willing to look past the December report and remain confident that the recovery in employment has not lost steam,” Peter Newland, an economist with Barclays Capital, said in a note.

Many other indicators suggest the recovery picked up strength during the second half of 2013, driven in part by stronger consumer spending and improved trade.

More importantly, the central bank tries not to overreact to financial market tensions.

“I don’t think tapering has anything to do with what’s going on in Argentina, or Thailand, or the Ukraine,” said Sam Wardwell, investment strategist at Pioneer Investments. “These [emerging market] problems were problems that were always out there and they just chose now to come out.”

“If the Fed doesn’t taper because of this market volatility, I think it sends a bad signal for the market that the Fed is beholding to the markets and not really a central bank,” Wardwell added.

Interest Rate

Bond-buying is one of two prongs in the Fed's strategy to boost the economy. The other is low interest rates.

So what will happen if the unemployment rate hits 6.5 percent? No much, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch economist Michael Hanson.

At some point in the next few meetings, Hanson anticipates the FOMC will scrap the 6.5 percent unemployment threshold. After all, the unemployment rate had been a poor proxy of the overall health of the labor market even before the Fed announced the 6.5 percent guidance in December 2012.

The jobless rate is declining much faster than the Fed expected -- hitting 6.7 percent in December. It is falling in partly because people are dropping out of the labor force and they are no longer counted as unemployed.

Hanson doesn't believe there's much of a chance the guidepost will be reduced to 6 percent or lower, and instead expects it to be replaced with a discussion of the broader outlook for the labor market.

“We think hitting the ‘threshold’ will force the Fed to formally change its guidance to more ‘qualitative’ thresholds for hiking rates,” Hanson said. “The result is a more flexible and robust threshold, but greater uncertainty about exactly what that threshold is.”

However, when wages start to rise, Pioneer Investments’ Wardwell said he hopes the Fed will focus on inflation.

“The challenge for the market is that when push comes to shove, is the Fed going to worry about inflation, or is it going to worry about keeping its words on forward guidance,” Wardwell said. “You don’t want the Fed to stay too loose for too long, fail to take the punch bowl away, and have an overheating economy.”

The 2014 Lineup

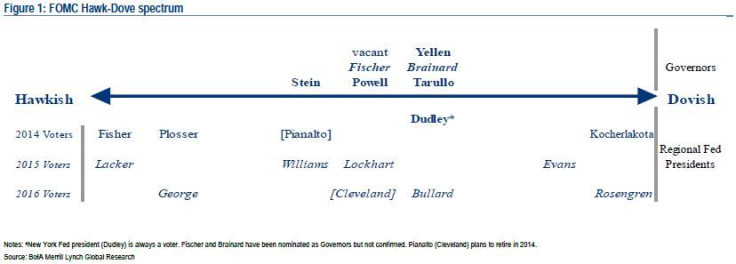

The January FOMC meeting will offer the first glimpse of a new lineup of policymakers.

Janet Yellen, Bernanke’s close policy ally and current vice chair, is due to succeed him on Feb. 1. She will also be leading a rather different group than the one that backed Bernanke’s aggressive stimulus measures last year.

Outside of all of the changes on the Board of Governors, four new regional Fed presidents will rotate into voting positions, joining the New York Fed president who has a permanent voting position on the FOMC. The remaining four seats rotate among the remaining 11 regional Feds in a regular three-year cycle; thus the voters in 2014 are mostly the same as those in 2011 and 2008.

“Yellen’s first year as Fed chair has the potential to be volatile, and the changing cast of voters does introduce some modest uncertainty into the markets,” Hanson said.

Last year’s voting regional presidents were fairly more co-operative. This year’s group seems to be a little more volatile. The dispersion of views among the voting Fed presidents is particularly wide, with Dallas’s Richard Fisher and Philadelphia’s Charles Plosser on the hawkish end, Cleveland’s Sandra Pianalto in the middle, and Minneapolis’s Narayana Kockerlakota on the far dovish side, according to Hanson.

That said, Hanson predicts Yellen will aim to stay the course.

Yellen’s Challenges

Refinements to the Summary of Economic Projections and a press conference after each FOMC meeting are likely high on Yellen’s agenda.

But while the Fed’s move to transparency is a good thing, Wardwell thinks “a Fed that reacts to the markets and holds press conferences to talk about how it’s reacting to the markets is a bad thing.”

“I think people have become too short-sighted.” Wardwell said. “Monetary policies take 12 months to work, so you really don’t need a press conference eight times a year.”

In terms of the biggest challenge facing Yellen, Wardwell believes it is to rebuild the Fed’s balance sheet.

The Fed's third round of quantitative easing began in late 2011 when its balance sheet was less than $3 trillion. Data released by the central bank showed the Fed’s balance sheet crossed the $4 trillion mark earlier this month.

“I wouldn’t call it a bubble, but they [the Fed] have to figure out how to get that balance sheet back to normal,” Wardwell said. “If you look at the European Central bank, Europe is a mess, but the ECB has got a lot of dry powder. The Fed really doesn’t.”

“The Fed needs to rebuild its reserve situation, it needs to get rates up so they can lower them again and shrink its balance sheet, so if necessary, they can expand it again,” Wardwell added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.