Mexico’s Missing Students: Relatives Of The Disappeared Aim To Galvanize US Support

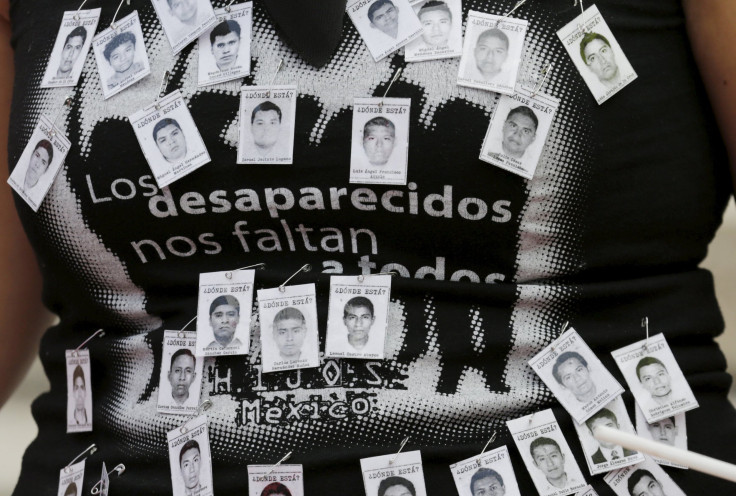

It’s been nearly seven months since 43 students from a rural teacher’s training college in Mexico disappeared, setting off a national firestorm of outrage over violence, corruption and impunity among the local police, gangs and politicians. Now relatives of the disappeared have taken their fight to the U.S. as their cause has broadened into a transnational leftist movement, finding solidarity with U.S. activists fighting for migrants’ rights and against police brutality.

Families and friends of the missing students from the Ayotzinapa teacher’s training college are wrapping up a sweeping tour through the United States this week. Since March, they have been traveling through more than 40 cities in a project called “Caravana 43,” stopping at local universities, community centers and political forums to rally support and draw attention to violence and corruption in Mexico. All three groups converged in New York City this week and plan to march to the United Nations on Saturday, the seven-month anniversary of the students’ disappearances.

“When our children leave school to pursue a profession, [the government] makes it very difficult for them to study,” said Maria de Jesus Tlatempa Bello, the mother of Jose Eduardo Bartolo Tlatempa, one of the students who went missing last September. She spoke during a press conference in front of City Hall in New York Wednesday afternoon. “Many of them migrate to other countries to have a better life. Many of them end up [in the United States]. Others arrive but don’t have jobs, and others stay in the middle of the street. As parents we suffer because we don’t know if our children live or die. But we thanked God, because our children got into in the Ayotzinapa teachers’ training school.”

The last day she saw her son was on Sept. 18, a week before police fired on students from the teacher’s school in Iguala, in Mexico’s southern Guerrero state. “We never imagined that they would be killed, massacred, and 43 students would be kidnapped,” she said.

Other activists with Caravana 43 drew parallels between the violence in Mexico with the U.S.’s surging protest movement over police brutality against unarmed black men. Two members of the caravan held up a long black banner reading, “Police Brutality Has No Borders.”

“We are going global with our program because what happened in Mexico is not just in our country,” said Felipe de la Cruz, a teacher from the Ayotzinapa school and a spokesperson for the relatives of the disappeared. “It has happened in other countries, in America and other countries on the other side of the ocean.”

“In Mexico, the police kill youths. In this country, the police also kill youths,” he said. “The difference is the place, but the crime is the same, and impunity continues.”

On Wednesday, relatives of the disappeared were flanked by local activists supporting their cause and tying them to social justice movements in the United States, including outcry over the war on drugs and mass incarceration, as well as immigrants’ rights.

“In Ayotzinapa they murdered students. Why? Because being a student is a crime?” said one activist who took the microphone before the relatives of the disappeared came out to speak. “I don’t accept it. For this reason, I support the parents of Ayotzinapa.”

“I am Mexican, and I wanted to study,” he continued. “But the Mexican government hasn’t given us the opportunity. I came to [the United States] when I was 10, and I had to end my childhood in order to work to support my studies. That’s what the system forces us to do. Young people cross the border, starve and go thirsty in the desert.”

In the months following the disappearances, the outcry from Mexicans fed up with violence swelled as investigators found mass grave after mass grave, none of which contained the remains of the missing students. Activists lashed out at government officials for mishandling the investigation. The political toll has been severe: Mexico’s attorney general and Guerrero’s governor both resigned from office as a result of the fallout. It’s also badly dented the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto, whose approval rating plummeted to all-time lows: Only around 39 percent of Mexicans approve of his leadership, according to a survey published in March by Mexico’s Grupo Reforma.

The members of Caravana 43 have ambitious demands. Overall, they want the Mexican government to reopen the investigation on the missing students. They doubt the government’s official theory that a local gang killed all 43 students, burned their bodies and dumped the remains in a local river. During the investigation, researchers recovered bags full of the presumed remains, matching a bone to one of the missing students. But they said the other remains couldn’t be tested, and an independent group of forensic scientists opened questions over the investigation, saying the government’s evidence collection methods left the samples vulnerable to tampering.

“Alive they took them, alive we want them back,” the Caravana 43 members shouted.

But they also want an end to the Merida Initiative, the U.S.-Mexico security agreement under which Washington delivers training and advisory services to Mexico for anti-drug operations. The U.S. and private companies can supply a limited amount of weapons systems and aircraft to Mexican authorities as part of the arrangement. But the Caravana 43 supporters say U.S.-delivered weapons are being used to kill civilians, as in the case of the Ayotzinapa students.

Speakers at Wednesday’s event in New York also demanded Enrique Peña Nieto’s ouster. De la Cruz called him Mexico’s “No. 1 killer,” since the police and corrupt officials who made such a crime possible all operated under his watch.

It’s unclear if any of their demands will be met: The Mexican government has already closed all lines of inquiry into the disappearances, and while Peña Nieto’s popularity has sunk, his hold on the presidential seat doesn’t seem to be threatened. The Merida Initiative, meanwhile, still has strong support from U.S. and Mexican authorities.

But the Caravana 43 supporters have made it clear they won’t rest anytime soon. “Ayotzinapa vive, la lucha sigue,” they shouted in unison. “Ayotzinapa lives, the fight continues.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.